Aerial view of projected development at Docklands, with the city beyond. Image Design Media.

Site plan.

Public space at New Quay, one of the first areas to be publicly accessible. The shimmering surface of one of McGauran Giannini Soon’s mesh-clad restaurant pods is to the right, with SJB/FKA’s apartments beyond. Photograph Peter Bennetts.

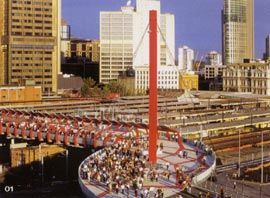

Overview showing the first public event on the Bourke Street pedestrian bridge, by Wood Marsh. Photograph Mike Leonard.

Rendering of Harbour Esplanade, designed by ARM and Rush Wright Associates. Image Design Media.

Looking north over Docklands Park, also by ARM and Rush Wright Associates, with the Harbour Esplanade in the distance. Image ARM.

Residential towers, designed by HPA, at Mirvac’s Yarra’s Edge at the south edge of Docklands. The landscape design for this section of the public promenade is by Murphy Design Group and EDAW. The Webb Bridge, by Denton Corker Marshall and Robert Owen, is in the foreground.

New Quay, seen across Victoria Harbour. The residential towers are by SJB/FKA Architects, the wateredge kiosks are the outcome of a design competition for RMIT students and were completed in collaboration with SJB/FKA Architects. McGauran Giannini Soon’s restaurant pods are to the far left. Photograph James Widdowson.

The promenade seen from the public space between the restaurant pods. Silence, by Adrian Mauricks, is seen in the distance. Landscape architects for New Quay are Tract Consultants

Looking from one restaurant pod, across the intervening public space, to the other. Photographs Peter Bennetts.

View along the restaurant-lined promenade at New Quay, looking toward the city. Photograph Liam Lynch.

DOCKLANDS UPDATE It is almost seven years since Ashton Raggatt McDougall’s innovative Docklands masterplan was released in 1996. Responding to its context, the plan opted for ‘fluid’ strategies of zoning, massing, and circulation, providing a counterpoint to the order of the city grid. The Docklands masterplan has since evolved and changed substantially as developers for particular precincts have come on board. Nevertheless, the precinct still demonstrates very different urban strategies to those of the city. Now with access routes open and several public spaces and buildings completed, it is possible to walk down to the dock and get a sense of Melbourne’s new waterfront.

Melbourne’s city grid was originally aligned with the Yarra River, at the point where navigable and fresh water meet, well upstream from the waters of Port Phillip Bay. With plenty of sites around the bay for recreational craft, the waterways close to the city were given over entirely to industry. The city’s connection to the river was further interrupted by the railways on Flinders and Spencer Streets. Now, instead of turning its back to the water, Melbourne is following the lead of many cities around the world, and restoring its waterfronts for leisure and accommodation. The process began with Southbank, and at Docklands, with 200 hectares of land and seven kilometres of waterfront to be developed, it promises to continue for many years to come.

Access from the city is now possible via the bridge at Collins Street or the pedestrian overpass at Bourke Street, both by Wood Marsh Architects. The city loop tram has been extended down to the water at Harbour Esplanade, and road access is possible from north and south. At the heart of Docklands is the football stadium, and while many Melburnians have visited here, it is a fairly introverted affair. Nearby, work has begun on several of the precincts, each in the hands of a different developer.

To the north, ARM have joined with Bates Smart and Rush Wright Associates in the design of the technology centre known as Comtechport, while to the south, in the Batman’s Hill precinct, the Bureau of Meteorology by Bligh Voller Nield is under construction. The new Webb Bridge, by Denton Corker Marshall and Robert Owen, provides a pedestrian link across the river to the Yarra’s Edge precinct, where two of six proposed towers have been completed. In the Victoria Harbour precinct, between the river and Victoria Dock, Bligh Voller Nield’s new headquarters for the National Australia Bank is well under way, and a residential tower by John Wardle Architects will soon begin.

Along the northern edge of Victoria Harbour, in New Quay, it is possible to stroll along the boardwalk and visit the various bars and restaurants that have opened there.

On one side, four apartment towers by SJB/FKA (formerly SJB/NFK) are raised on a sixstorey podium, with carparking to the rear. On the other, a series of pods containing bars and restaurants complement those in the base of the podium. Between the two largest pods, designed by McGauran Giannini Soon, the boardwalk extends out and down to the water. Alongside New Quay, a plaza will provide access to the dock from Waterfront City, a “retail street” precinct extending back to Footscray Road, recently awarded to Hassell.

Although carving up the site in this way brings some risk of fragmentation, guidelines and urban design strategies should provide continuity to public space and amenity. Docklands Park will provide a strip of open space connecting north to south, although the landscaped elements are away from the water’s edge. However, maintaining pedestrian access to the water in the form of a continuous walkway will provide the most remarkable aspect of the entire project.

A walk along New Quay gives a hint of what this might be like. Although some of the promotional material suggests otherwise, this area will be predominantly in shade.

This may not be a problem on a grey Melbourne day or in the heat of summer, but it could prove to be a little cool here on occasion. However, changes of level and material combine with planter boxes to give a feeling of enclosure, and sitting al fresco or behind glass looking out at the water is quite a pleasant experience. McGauran Giannini Soon’s pods also provide protection, while still connecting to the water. Instead of an iconic formal gesture, these buildings adopt an almost formless quality. Subtle shifts of surface in translucent glass tie the pods to the pedestrian promenade, giving way to layers of brass, glass and stainless steel mesh hovering above the water.

The view from here is still mostly of construction sites, with the towers in the distance acting as a reminder of the scale of the Docklands redevelopment. The view will change markedly as more stages are completed and as central pier becomes accessible. Interestingly, what is most visible is not blue water yachts or whitecaps but the central pylons of the Bolte Bridge, part of the freeway system that has diverted traffic away from the area and freed it up for development. The pylons are a stark reminder of Melbourne’s industrial character, and of the docks that still operate on the other side.

The water here is not the kind one might encounter at a Pacific island resort, and the industrial character and cooler climate are what will give the Docklands a unique identity. Fortunately, nautical themes have so far been avoided, and the area has been designed with typical Melbourne elegance. The public art program has provided some interesting pieces, especially John Kelly’s Cow Up A Tree. Diversity is a key promise for most of the projects, but with the Government aiming for a public to private funding ratio of 1:70, developers are clearly targeting a narrow demographic. The result is a rather homogenous collection of apartment towers, waiting to ride out a forecast lull in the property market. This will soon pass, of course, and provided its public space is protected, Docklands will live up to its promise of connecting Melbourne to the water.

SCOTT DRAKE IS A SENIOR LECTURER IN ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE.

DOCKLANDS – PUBLIC REALM OR PRIVATE PLAYGROUND I remember taking part in a weekend workshop on Docklands couple of years after I graduated. The Planning Department arranged a handful of noted architects to lead a charette aided by small number of assistants like myself.We took a boat tour to familiarize ourselves with the site and then set to work in one of the many office-shed spaces that were once used by cargo and shipping companies. Barry Marshall was the design leader I was assigned to, and I particularly remember Barry’s instructions about the precise way to tear long pieces of yellow trace from the rolls provided. The other thing that sticks in my mind is the vague sense of the overwhelming impossibility of the task. This impossibility seemed to dog Docklands for many years as successive governments, and no doubt Planning Department staff, tried to figure out a way to kick-start this enormous project.

There were many other docklands to look to as models for our own. London’s docks, for one, were being developed at the same time and some extraordinary, as well as a whole lot of ordinary, projects, were emerging there. Massive urban projects were also underway in Berlin and Paris. Melbourne, however, having been hit pretty badly by a massive building recession, was struggling to think beyond the opportunistic possibilities of expanding prime real estate frontage, via an extension of Collins Street, over the railway lines and into Docklands.

It was with a sense of this difficult history, and with knowledge of the many transformations that subsequently took place, that we began thinking about the “Icons” restaurant project in 2000. By now the flavour of Docklands and New Quay was all but established. A strategy for a “public” realm was in place, including an artworks placement strategy and a comprehensively planned commercial and entertainment promenade on the waterfront. The prior industrial character of the precinct had been expunged from the face of the new Docklands and we were not allowed to construct any reference, however oblique, to this past. The context, then, was a tabula rasa. But what was less clear to anyone other than the architects already working in the precinct (Nation Fender Katsalidis and Synman Justin Bialek) – was how to banish that sense of ersatz reality that inevitably takes hold of newly designed and occupied precincts.

One strategy widely used to counter this effect is to commission a number of architects to work in the same locality, so as to approximate the differences in texture and form that naturally occur in a precinct over time. With this in mind, SJB/NFK, proposed a design competition to their client MAB that would allow other architects to be involved in New Quay. This strategy, however, often yields strange results – it can end up in a juxtaposition of diverse elements which, though respecting the formal scale and envelope, lack the delights and surprises of an old city (for example, Berlin). However, in some perverse way, the strategy did work at New Quay. This was due to the massive scale difference between the main residential towers on north side of the promenade and the modest scale of the pavilion-like buildings we designed on the water edge.We could simply be different to all else happening on the site.

To counter the sense of ersatz engendered by the “all new”, we sought to design two pavilions that would relate to the open public plaza between them in a way that did not mean a completely static relationship between the user and the buildings. The success of a public space depends largely on its fine grain – often this is where the influence of time has a positive effect on the measure of “well-being” that we rate our public spaces with. Re-establishing this grain became a priority for us with “Icons”.

As I look around Docklands now – with Mirvac’s development on its south side, Lend Lease’s on the city side, and the MAB precinct we worked in along the Dudley Street extension – I am reminded of Peter Elliott’s comment about the various obligatory stages a city must go through in the hope of achieving successful transformation. Its functions must go through gradual stages of disuse, marginal use, and finally redevelopment. Unfortunately, the possibility of a gradual transformation for Docklands was removed long ago, and this has come at a great cost to the public domain. What was removed through demolition is virtually impossible to recreate with new construction.

Despite the great success of the promenade at New Quay, this is a problem that will continue to dog Docklands. The accusation that it’s not made for the pedestrian and it’s not catering for the public is exacerbated by the lack of convenient public transport and the odd decision to define each site through the use of boom gates and paid parking facilities. Not the right message we want to give Melbourne if we are serious about Docklands being a place for all to enjoy – if not in terms of a “lifestyle” difficult to afford but at least in terms of a place for everyone to visit and enjoy.

ELI GIANNINI IS A DIRECTOR OF MCGAURAN GIANNINI SOON AND PRESIDENT OF THE VICTORIAN CHAPTER OF THE RAIA.