The new Business School building at the University of Technology, Sydney (UTS) is located in Ultimo, a cultural and educational precinct of inner Sydney. The building’s function is primarily postgraduate and executive education, but it serves the university as a whole and is intended to represent the innovative thinking that underpins the teaching, learning and research undertaken by the Business School. Named for Australian-Chinese businessman and philanthropist Dr Chau Chak Wing, who donated substantially to the project, the building is strikingly different from any other in the vicinity and it clearly generates plenty of interest at street level as pedestrians are drawn closer to inspect, photograph and engage with it. Responses range from aversion to delight, yet many people are unsure about the dramatically sculptural work. This ambivalence is intriguing because the building has been designed by Frank Gehry, 1989 Laureate of the Pritzker Architecture Prize, an architect whose significant yet polarizing body of work is both admired and reviled worldwide. But perhaps it is appropriate that the Sydney audience will not simply accept that its Gehry building – his first in Australia – will be a great one deserving immediate approbation.

Examining the building beyond immediate concerns such as its appearance, the overall cost to UTS and the difficulty of its construction reveals an architecture that is challenging in at least three key ways. Firstly, it challenges more traditional notions of context in the sense that it thrives in both a local, urban context and in a virtual, global one. Secondly, it challenges construction norms by taking a standard construction method – in this case, brick veneer (a brick skin tied back to a structural frame) – and achieving an incredible fluidity of form and texture that has already raised the profile of the highly skilled bricklayers who laid in order of 320,000 bricks by hand, following the 3D construction model. Thirdly, it goes back to a tradition of university buildings that offers identity and a place for students to gather and be inspired, rather than simply providing accommodation for students gaining degrees through the system. This is important now because universities must embrace online learning and engage with a highly literate and mobile generation of learners.

A stainless steel stair in the main lobby – manufactured by Urban Art Projects – is one of the sculptural forms within the building.

Image: Peter Bennetts

How does this building challenge the value we attribute to architecture that belongs to place and responds to context? On the one hand, it fits into its context in scale and proportion, colour and use of local materials, and through its enhanced connection with the surrounding streets and The Goods Line – a pedestrian spine along a disused railway track currently being re-landscaped alongside the Business School. It is contextual, as described in the UTS media release: “the exterior has two different but related personalities; an east-facing, undulating brick facade acknowledging Sydney’s sandstone heritage and a western facade of angular glass shards reflecting its contemporary surrounds.” On the other hand, Gehry radically distinguishes the building from its local context by taking the familiar architectural building type of UTS and other neighbouring institutions and morphing that typology into a wildly irreverent, lifelike being. This act of manipulating form allows the creation of remarkable and memorable images, such as the one used by UTS to advertise the new Business School building in print media, months before the official opening. This apparent reduction of architecture into a singular image – sometimes one associated more closely with the architect’s oeuvre than with the building’s place and use – is unsettling. Architectural imagery – as with all image making – is now global currency, and in this sense, the architecture could be located anywhere. “Bilbao, Paris, Los Angeles, Sydney; whatever program, whatever place, a Gehry is above all a Gehry,” said Sydney-based architecture critic Elizabeth Farrelly of Gehry’s instantly recognizable work. 1

Bricks, including five types that were custom-made for the building, have been intricately corbelled to achieve the building’s remarkable fluid skin.

Image: Peter Bennetts

These images, however, are no match for experiencing the actual building. Up close, the plastic, fluid quality of the Dr Chau Chak Wing Building creates an encounter and connection that are wholly physical. Its extraordinarily complex construction included five custom-made brick types manufactured specifically for the building by Bowral Bricks and laid with great skill by master bricklayer Peter Favetti, who came out of retirement to work with his son and the bricklayers of his business on the project. The brickwork is heavily corbelled and carefully executed to an exacting and highly detailed design. The undulations of the brick facade and the abundance of idiosyncratic visual and tactile detail make “being there” a highly engaging and personal experience. Comparisons with architects from other eras such as Gaudí and Lewerentz come to mind. Gaudí because of the playfulness and freedom of the form, and Lewerentz for the extensive use of expressive brickwork and the way materials such as brick and timber are used to create a sense of space and place. There are differences, of course – Gaudí and Lewerentz were not influenced by the possibilities of computer modelling and did not live in a world that communicates so predominantly through visual media, which is the context in which Gehry works today.

The third challenge faced in the realization of the Dr Chau Chak Wing relates to the way educational facilities might engage learners. Parallels can be drawn between the physical experience of this building and the education model that promotes face-to-face interaction and communication. While UTS belongs to a global conversation, and it is clearly useful for any university to have a global reach, “being there” – to experience both the architecture and the teaching – is most certainly also an important aspect. Professor Shirley Alexander, Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Vice-President (Education and Students) at UTS, was closely involved in the design process, working with Gehry Partners and local practice Daryl Jackson Robin Dyke as they interpreted the education brief set by the university. Professor Alexander noted that Gehry was very interested in the education model and embraced the idea of the building extending to a new model that combines the best of online learning with the best of a face-to-face experience. Increasingly, along with perhaps all other universities, UTS sees the campus as a high-value, high-quality experience for personalized learning – something that cannot be done online. Consequently, there is no standard lecture theatre in the Business School; instead, there are oval-shaped spaces that are described as high-touch experience spaces, supported but not dominated by technology. Some of the key spaces are for just forty people, allowing participants to engage with each other. There are also informal spaces and kitchens, informal learning in the circulation space and a cafe that links to The Goods Line, responding to students’ desire for natural light, food and drink where they study.

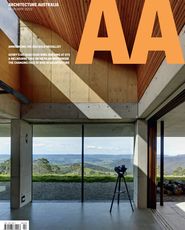

The eastern edge of the building connects with The Goods Line, a pedestrianized spine along a former railway line currently under development.

Image: Peter Bennetts

It has been estimated that the Dr Chau Chak Wing will attract 24,000 interstate visitors and 2,000 international visitors each year, adding $36 million to the tourism industry through spending by business event visitors annually. 2 UTS sees great value in the ability to be recognized both locally and internationally, and thus the building is a key project in the City Campus Master Plan – UTS’s ambitious scheme to overhaul its facilities. A building that goes beyond satisfying basic functional requirements, that produces this richness and complexity, and that draws people in, whether they are viewing it from an academic standpoint or simply discovering it in the street, is a good building. Yet when this result is achieved by an international architect, questions arise about why local firms were presumably overlooked to lead the design. Perhaps to be fair, we should also more regularly ask whether we need non-local and international firms to join our many great local architects in lifting the expectation of design excellence whenever the opportunity presents itself in the form of a willing and able client. The privileging of local firms would seem to be an argument not founded on the goal of achieving a great city. This project raises the profile of architecture for the benefit of all architects, promotes the UTS brand worldwide while also enhancing the local university community, and delivers a richly layered building for the benefit of the people who interact with it as a piece of the city.

1. Elizabeth Farrelly, “Frank Gehry’s UTS building is no Opera House,” Canberra Times , 10 July 2014. http://www.canberratimes.com.au/comment/frank-gehrys-uts-building-is-no-opera-house-20140710-zt144.html (accessed 21 January 2015).

2. Independent modelling by Urbis, cited in UTS media release, December 2010.

Credits

- Project

- Dr Chau Chak Wing building

- Design architect

- Gehry Partners, LLP

- Executive Architect

-

Daryl Jackson Robin Dyke

- Consultants

-

Aboriginal archaeological investigation

Dominic Steele Consulting Archaeology

Accessibility consultant Morris Goding Access Consulting

Acoustic consultant Marshall Day Acoustics

Archaeology Casey & Lowe

Brick manufacturer Austral Bricks

Bricklayer Favetti Bricklaying

ESD and services AECOM

Early works contractor A.W. Edwards

Facade Arup

Heritage consultant Godden Mackay Logan

Main contractor Lendlease

Project manager UTS Program Management Office

Stainless Steel Stair Urban Art Projects

Statutory planners RPS Group

Structural engineer Arup

Traffic and transport Arup

- Site Details

-

Location

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

Site type Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2014

Category Education

Type Universities / colleges

Source

Project

Published online: 14 May 2015

Words:

Jennifer Calzini

Images:

Peter Bennetts

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2015