Small

… is appropriate for our time of increasing density and scarce resources.

… is an acceptable risk within contemporary procurement processes.

… is reliant on the immediate context so tends to be inherently ethical.

… is architecture’s most prevalent and effective scale.

… is both innovative and subservient to precedent and planning.

… transgresses disciplinary boundaries.

… enfranchises the architect.

… describes the majority of practices in Australia.

… captivates those outside the discipline.

Smallness, or embracing limit

Size is among the central preoccupations of an architect. We set the size of elements to enable proportional relationships in the structures we facilitate. There is size within the project, as there is the size of the project in its setting.

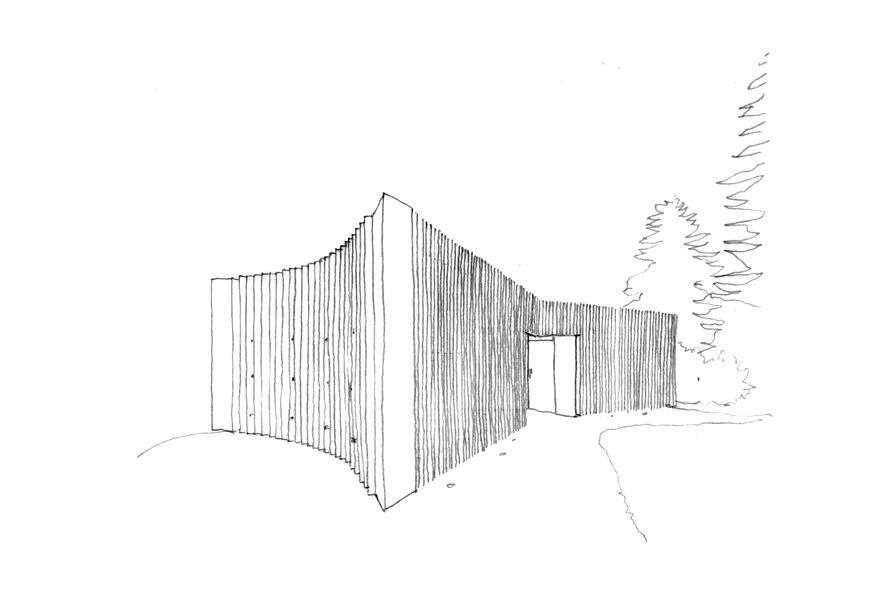

Of course, measures of size, be it small or large, are relative. The diminutive in one context takes on a very different stature in another and so empirical measurement that seeks binary categorization will be thwarted. In this sense, we define Smallness in architecture as the working towards reduction in a physical sense, while always seeking to amplify joyful experience.

Bigness

It is now 25 years since Rem Koolhaas penned “Bigness or the problem of large”1 in order to theorize the impact of capitalism on architecture. The end of the twentieth century saw the widescale proliferation of the extra-large buildings promised by Modernism decades earlier. The conference centre, office tower, airport, mall and casino borrowed the organizational traits of an increasingly connected and complex world to define a unique new aesthetic, often conflating large buildings with entire urban precincts.

Koolhaas’s call to arms suggested we “ fuck context” and enjoy the unique “regime of complexity that mobilises the full intelligence of architecture.” This profligate vision for our discipline, which ended with the prophecy that “Bigness surrenders the field to after-architecture,” did indeed prove prescient. Over the past quarter of a century, the extra-large building has had a tendency to erase not simply the autonomous architect author, but architecture altogether. Even in urban regeneration projects in which there remains a strong architectural agenda and resolution – projects like Euralille, Potsdamer Platz, Battery Park, Docklands and Barangaroo – there has tended to be a distinct lack of social diversity, cohesive communities and vibrance within the street.

Small beginnings

At the other end of the scale, Cicero said, “Omnium rerum principia parva sunt,” which Paul Kelly may have paraphrased when he sang “From little things big things grow.” Small in this sense – the individual emergence of a thought, a project or a practice to gain capacity and scale up over time – is a well established phenomenon, but it is not the small of this polemic.

We are more interested in how, now and into the future, we might deliberately adopt limit as an armature for our collective endeavours. Rather than building big and with profligate resources – a manner that almost assures a heightened experiential impact and arresting architectural image – our aim would be to engender that impact with less. This is certainly more difficult, but what results is a form of architectural elegance, one in which small projects leverage ingenious simplicity for great impact.

Scaling up

Small also brings to the fore community and environmental concerns, which scale well from the small, but tend to be lost, or relegated to technologically driven amelioration techniques, in larger systems. Noam Chomsky has observed that people have the capacity to act differently in their family or community groups than they do within larger cultural or economic frameworks: “You can be one thing at home and you can be something else in an institutional role. You can be destroying the world in your institutional role, consciously, and loving your children at home.”2 Slightly more optimistically, Hugh Mackay places hope in a trickle- up process: “How we contribute to the miniatures of life – in our own family, street, suburb or town – will ultimately help to determine the big picture.”3

Small pieces loosely joined4

How we might enable the retention of small-scale legibility and autonomy within a large system becomes a crucial question. The structure of the internet and other prevalent digital social systems has demonstrated the effectiveness of a loosely organized network to give order to small pieces of evolving information. This organizational framework can be used to reposition our understanding of potential dispersed systems in other fields.

Within the realm of small-scale architecture, Instagram and other visual digital propagation platforms have seen a shift in the frame of reference from the individual project, or practice, to a wider consideration of a collection of initiatives working with shared manners and so values. This exposure has enabled the appreciation of a sophisticated visual design culture to evolve within wider society – which, in turn, increases the expectation for design quality in the infrastructure of the everyday.

The feedback loop of this digital connectivity also creates some interesting impacts within the discipline. While it can be argued that the idiosyncratic diversity of projects and practices relating to place lessens as details and techniques are more directly appropriated from other jurisdictions, it is also true that the increased speed and prevalence of these appropriations propagates new knowledge and enables a more adaptive design capability within the system as a whole. Happily, within this system we are also seeing the sharing of ideas and initiatives to establish some quite coherent and wide-ranging value systems, with perhaps Parlour and Architects Declare being the most profound to date.

Joyful loos

This notion of small pieces loosely joined also plays out in compelling ways in urban contexts. The City of Sydney, along with adjacent councils and civic authorities, has over the past couple of decades embarked on a program that is so loosely connected as to be almost imperceptible – but, in hindsight, has generated an enviable legacy of small-scale public infrastructure. This has manifested in different ways but is most present in the distributed network of small-scale pocket parks and public toilet facilities.

Crucially, commissioning authorities have understood that the potential of the amortization of development risk inherent in the spatial and temporal dispersion of small projects enables engagement with more adventurous procurement conditions.

The humble toilet block, which traditionally has been among the most problematic of public places, has leveraged architecture to create places that are both private and open, and that pleasingly manifest place, elevating the most prosaic of acts to one that enables joy. The power of Rick Leplastrier’s little courtyard building at Mosman, or the hand basin at Chrofi’s Lizard Log, or the subaqueous interior at North Bondi Amenities by Sam Crawford Architects with Sonia van de Haar, is fundamentally affirming.

Over the same period, the City has been commissioning JC Decaux to provide prefabricated automated toilet facilities across the city. This centralized approach is efficient, blue-lit, clean and joyless.

Robust to this crisis, robust to the next

We write in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic – aghast, frankly, at the devastation that has been caused by the global spread of a novel virus. Upwards of one billion people have spent the past weeks locked in their homes. We face the spectre of closed international borders into the future. Globalization has been abandoned for the kind of localism not seen in our lifetime.

Seeking the opportunity within crisis, thinkers such as Arundhati Roy have suggested we see the pandemic as “a portal”5 to enable us to reassess how we are in the world, while Bruno Latour asks “Is this a dress rehearsal?”6 for the larger looming environmental crisis.

At the heart of the lockdown is the fundamental repositioning of the urban condition as one in which people move about less. Certainly this has had some negative impact. But it has also resulted in a radical reduction in CO2 emissions and significant improvements in air quality. We have seen our social networks refocus on neighbours and those within our immediate vicinity in ways that have been most rewarding. With our lives suddenly stripped of layers of extracurricular commitment, we see time extend in a manner most unusual.

Although our physical footprint is radically reduced, we still reach out to connect across the city and the planet. We use digital platforms to catch up with family, conduct endless meetings and enjoy the occasional after-work drink; we teach students located on this and different continents simultaneously; foreign movies beam into our homes; we purchase dinners, hats, books and gym equipment, all of which are delivered to our door. While we are physically isolated, it has never been so apparent how intrinsically we remain connected.

On the horizon, we see the vast edifice that is the central business district and, at this moment, it frankly looks a little ridiculous. The billions spent on cross-city tunnels and inner-city spaghetti junction tollways take on a similar absurdity as the massive transport network required by the compact centralized city becomes suddenly redundant. At the same time, we recognize in our homes the potential for places of work, food and energy production; a mixed-use development positioned as the nucleus of production and community interaction, rather than what had been until recently a retreat and repository for the detritus of our consumerist urges.

Disperse urbanism

The resultant urbanism of Small is dispersed. Dense and super-local, it would comprise a series of overlapping spatial networks centred on small-scale community-based facilities – the market, the school, the park. These networks would become polycentric to the point that density is more evenly distributed and the notion of a centre in any physical sense dissolves.

The outcome would be diverse-use neighbourhoods in which the physical needs of the community are largely satisfied by endeavours of the same community, while digital and goods delivery networks enable connection and distribution in a wider sense.

This city, as archaic as it is emergent, would establish not simply diversity but enviable resilience via the fragmentation and repetition of constituent parts. This is inherently inefficient in a Fordist sense, but the networked redundancy in the system would enable robust evolutionary change, in a resilient and sustainable manner.

As utopian as this speculation may seem, the mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, recently stood on a re-election platform for the transformation of her metropolis into a series of super-local “15-minute cities.” Smallness is the crucial precondition for the success of this initiative and demonstrates that architecture may actually find greatest social resonance at the scale of the everyday.

1. Rem Koolhaas, “Bigness, or the problem of large” in Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau, S,M,L,XL: O.M.A. (New York: The Monacelli Press,1995).

2. Noam Chomsky, in Chomskian Abstract , a filmed interview with Cornelia Parker, 2007.

3. Hugh Mackay, “The state of the nation starts in your street,” 2017 Gandhi Oration, available at youtube.com/ watch?v=jFoOHPfjTXU (accessed 20 May 2020).

4. David Weinberger, Small pieces loosely joined: A unified theory of the web (New York: Basic Books, 2002).

5. Arundhati Roy, “The pandemic is a portal,” The Financial Times , 4 April 2020, ft.com/content/10d8f5e8-74eb-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca (accessed 19 May 2020).

6. Bruno Latour, “Is this a dress rehearsal?”, Critical Inquiry, 26 March 2020, critinq.wordpress.com/2020/03/26/is-this-a-dress-rehearsal (accessed 19 May 2020).