Repair, Australia’s interpretation of the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale’s overall theme of “Freespace,” opened on a delightfully sunny morning at the Giardini. A happy crowd of a hundred and fifty or more waited patiently in the dappled shade at the foot of the ramp that rises gently toward the Australian Pavilion entrance. With opening remarks made and ribbon cut, we entered the black box. Inside the atmosphere was sombre. In the far left corner of the space, at right angles to each other, two large, silent two-channel video projections offered simultaneous different perspectives on a landscape – in elevation on the left and from above on the right.

A gently undulating topography of plants from the Victorian Western Plains Grasslands almost filled the pavilion, causing us to tread carefully and behave courteously. In the dim light, individuals quickly spotted and colonized a small cluster of soft cylindrical poufs in the centre of the grasslands. The rest of us stood, filling every available space in hushed conversations … and then suddenly bright light from above washed the room, filling it with whiteness, intense but not uncomfortable. Surprise and self-awareness brought chitchat and a heightened volume almost immediately. Now we were looking across the grasslands at each other, the videos complete and clothing, bags, hairstyles, all rendered in the white light. The astonishing greenness of the vegetation, an instant reminder of the necessity of light and colour for life. But where was the architecture? No models, no drawings, no abstract inscriptions on the bare white walls – we were left pondering the architecture of the topography, the containers supporting the plants and the distribution of the lights, their ceiling plan reflecting the distribution of the plants below. And then, as suddenly as it had arrived, the white light disappeared and we were treated to the next in the series of videos – all two-channel and free of titles, explanatory text or dialogue – that would unfold over the course of the day.

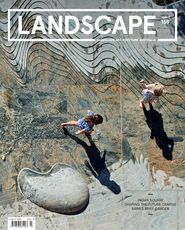

Silent, two-channel videos simultaneously present different perspectives of selected projects by Australian practices.

Image: Rory Gardiner

Creative directors Mauro Baracco and Louise Wright of Baracco and Wright Architects with artist Linda Tegg have curated an environment unlike any of the other pavilions at this year’s biennale. Physically, one could say the environment consists of five components – the topography of plants, the videos, the white interior of the pavilion within which the first two components are placed, the black exterior of the pavilion and the Giardini beyond – but it is not that simple. The pre-eminent component is time. Time pulls all of the exhibition’s elements together. And this exhibition requires time, it requires patience, but it is by no means tedious. It allows you to leave and come back. It talks to you slowly, it is sensuous – no information overload here, no biennale-fatigue.

The main component of the exhibition, Grasslands Repair , includes more than 10,000 plants from 65 species of Victorian Western Plains grasses.

Image: Rory Gardiner

I get the impression that for the curators, this project has been a continuous work since their commission, or even before. No sooner had they been commissioned, with paperwork completed, than they were travelling to Italy along with the seeds of the selected grasslands species. With horticulturalists from the Istituto Professionale di Stato per l’Agricoltura e l’Ambiente “D. Aicardi’” they have been literally growing the exhibition ever since. During their opening remarks, they highlighted the technical difficulties associated with this kind of work. Many of the plants died or failed to germinate. These difficulties would be well known to horticulturalists, but perhaps not that obvious to passers-by.

However, the exhibition raises more profound questions. It asks us to be more conscious of the environment, habitat and cultural history within which we work as designers. And more than that, to engage in acts of protection and even reparation. It is hard to argue with this, but in reifying nature, the exhibition contains within it, as philosopher Timothy Morton warns, the potential for further distancing the type of nature “over there.” In the realised exhibition, however, the technical requirements for the plants’ survival during the six months of the biennale have been assimilated into the overall work within the pavilion, but not hidden. A balance is deftly found between horticulture, atmosphere, information and architecture.

I cannot help thinking of the way in which the exhibition reflects our world, the ever-increasing surface area of food production under lights and glass, shrinking habitats protected within national parks, irrigation diverting water. Repair brings us into contact with ourselves as nature, in an increasingly mechanized world. Baracco describes the grassland installation as a “provocation,” a “reconstitution” – the vegetation is real, but its configuration is contrived. The sources of energy transferred from the Italian grid to the some 10,000 plants are printed on the wall: “64 percent fossil, 21 percent hydro, 9 percent wind and solar, 5 percent nuclear and 1 percent geothermal,” leaving us in no doubt as to the plants’ remove from their “natural” source of solar radiation.

The exhibition’s living topography of plants is sustained by a lighting feature, Skylight , which simulates the sun’s energy.

Image: Rory Gardiner

The Repair exhibition signals crisis, but the crisis it responds to is not about architecture. Rather it is about mechanization, food production and logistics. It is not that architecture, per se, is destroying landscape – rather, it is that we are. The creative directors’ response to the Freespace theme, as evidenced in their opening remarks, asks us to “consider the earth as a client.” Doing so does not necessarily mean a reified nature and the work on display here goes some way toward proving this. Kullurk/Coolart: Somers Farm and Wetlands by NMBW Architecture Studio with William Goodsir and RMIT Architecture subtly modifies land to transform hydrology, enabling the clients to continue to farm while at the same time improving biodiversity. “Repair,” in this instance, is not simply abandoning land to nature. The portrayal of walkers, cyclists and pet dogs enjoying Glebe4: The Foreshore Walk – JMD Design’s reconstitution of harbour foreshore and mangrove habitat – is unashamedly suburban in its slowness. The landscape within which Baracco and Wright’s Garden House is immersed is shown as it is, or more precisely as you would imagine it to be, with or without the house. And yet the house, in interacting with it, becomes it. In a biennale that, despite the overall “Freespace” theme, seems to harbour a distancing of nature, Repair takes a step in a very particular direction. The idea that architecture, by coming into contact with an immersive environment, both changes it and simultaneously becomes it is what we experience.

Repair is a brave and risky undertaking. The projects on display are modest, but each work touches a larger reality, a system or process that exists beyond the immediate architecture. The exhibition itself is fragile and, despite all of the research and preparation, a little unpredictable. The plants will be in a perpetual state of springtime, in a box that cannot be precisely controlled, where humidity levels are a known problem. If the plants wither, will the curators leave them in place? Answer: yes/maybe! But to what extent?

Repair demands your attention and time, but it is generous and sensual, and in being so it somehow gives time back.

The 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale, including the Repair exhibition is open to the public from 26 May to 25 November 2018.

The 2018 Australian Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale creative team led by Baracco and Wright with Linda Tegg also included architect and anthropologist Paul Memmott, landscape architect Chris Sawyer, landscape architect and urban designer Tim O’Loan, ecologist David Freudenberger, curatorial advisor Catherine Murphy, and architects Lance van Maanen and Jonathan Ware.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 29 Aug 2018

Words:

Dermot Foley

Images:

Rory Gardiner

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2018