AUSTRALIAN ARCHITECTURE IS CURRENTLY ENCRUSTED WITH RUST. WILLIAM TAYLOR SPECULATES ON WHAT THIS MIGHT SAY ABOUT CONTEMPORARY ARCHITECTURE AND ITS CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE AUSTRALIAN LANDSCAPE.

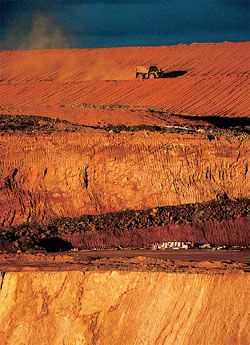

Superpit, Kalgoorlie.

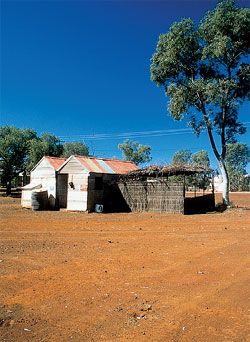

Gwalia heritage miner’s village (Leonora,WA).

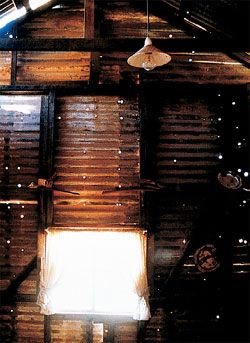

Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, by Wood Marsh, rust detail. Photographs William Taylor.

The remote Karijini National Park Visitors Centre, by Woodhead International. The weathered steel matches the red earth on which the building rests, constructing a reverential relationship to the landscape. Photograph John Gollings.

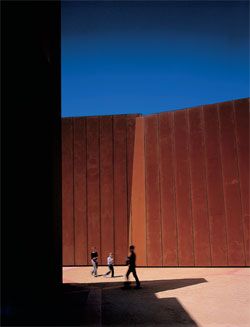

The rusted form of the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, by Wood Marsh, celebrates the everyday urban landscape – metal and bricks, factories and warehouses. Photographs Derek Swalwell.

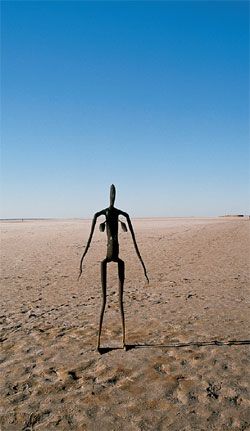

Inside Australia by Anton Gormley casts landscapes like the Australian outback as places devoid of history. Photographs William Taylor.

IF RECENTLY COMPLETED projects are any indication of emerging trends and national sensibilities, then there has been a renaissance of rust in Australia. For years the bane of architects and builders, we are now encrusted with the stuff and happily so. Notable projects in both urban and remote areas are complemented by scores of lesser buildings – beach houses and backyard additions, park and street furniture – made from rusting metal and dreams of decay.

Offhand justifications for using self-weathering (core-ten or T-1) steel, entail frequent claims regarding the protective patina it acquires or poetic appeals to the genius loci of our wide brown (read: ruddy, russet or rusty) land. But these do little to account for this trend. Glib pronouncements of a new Australian style should be checked by thoughts of former times when rust was something to be banished from buildings, not only because it threatened their structural integrity, but as it could be interpreted as a sign of human neglect. If rust has overtaken stainless steel and polished surfaces as tokens of high style, what does this say about changing values and our sense of ourselves? As a substance of particular properties, to be inhibited or turned to imaginative purposes, rust is a newcomer, relative to the industrial age. Once denoting corruption of various kinds, the term has come to denote an impurity integral with novel, highly refined alloys and new occasions for using them.

Core-ten steel was popularized in the 1960s and used on prestigious buildings like the Ford Foundation in New York City by Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo. It was fashionable – that is, until rust stains spread from facades onto pavements and threatened the distinctive separation of building and landscape, figure and ground desired by architects of the International Style. Core-ten was more likely tolerated on aesthetic grounds when used for public sculpture, as with the works of Albert Paley in the 1980s and 90s, though the assemblage of form and obvious decay could still pose a threat to public sensibilities, depending on the choice of setting. Richard Serra used the material for a series of “arc” sculptures, notably for his controversial Tilted Arc installation for Federal Plaza in New York City, which was ultimately dismantled and replaced by Martha Schwartz’s more pedestrian design of curving park benches. More recently, weathering steel for public sculpture and buildings has joined the list of other popular “natural” materials like stucco and wood in heritage-conscious areas – particularly where obtrusiveness or glare is a problem.

Certain moments in Western thought prefigure our complex appreciation of rust today. In the Oxford English Dictionary two definitions stand out, firstly, “The action or process of oxidating; combination with oxygen; conversion into an oxide or oxygen-compound” and secondly, “Moral corrosion or canker; corruption”. The view of rust as an action or process is counterpoised to one whereby the substance represents a threat to personal integrity, just as corrosion threatens the soundness of a ship or building. The understanding of rust as the outcome of a process of oxidation was based partly on developments in chemistry in the late eighteenth century, particularly the language of atomic chemistry invented by John Dalton and his contemporaries. Thoughts on rust in an age of science were also guided by analogies drawn between the observations of decay in different materials. In 1770, prior to modern theories of combustion, George Stahl, a German physician, likened the action of rust on metal to the charcoal that forms on wood during burning. John Tyndall, writing in 1863 of the propulsive force of heat in the human body, described what we now call carbon dioxide as “the rust of the body, which is continually cleared away by the lungs”. It was but a small leap of the imagination for poets and moralists to find, in the burning of wood and the rusting of metal, language to lament the physical and spiritual decay of humankind or, alternatively, the value of age. The authority of Scripture was frequently called upon for support, as in the book of Matthew (6:20–21) and advice to “lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust doth corrupt, and where thieves do not break through nor steal: For where your treasure is, there will your heart be also.” Contrasting this association of rust with corruption, Alexander Pope noted in 1737 that “Authors, like coins, grow dear as they grow old; It is the rust we value, not the gold.”

Both sentiments bring to mind the ascetic movement known as pietism. Practised by members of several Christian sects, though particularly popular among Lutherans, pietism called for modesty and abstinence in the conduct of personal life. Applied to architecture it encouraged the design of buildings with equal restraint, usually with modest scale and limited ornamentation. The American Shakers were pious in both regards, known for their unassuming buildings and ways of life. In Australia a pious (or Lutheran?) respect for landscape foregrounds efforts by designers to build upon the bounteous deposits of iron below ground by placing rust-ridden things upon it as though anything appearing more permanent would be impudent.

›› Here the land has carried such weight of meaning for some time. Glenn Murcutt’s encouragement to “touch the ground lightly” is now largely a cliché, though his advice should not be taken lightly. It is indicative of a view shared by his admirers outside Australia of the uniqueness of the antipodean environment and for many within the country of the exceptionality of something akin to the “Australian experience”. There are other factors at work here, though. The growing importance of environmental concerns worldwide, the prominence in the academy of philosophies that stress the inherent meaningfulness of building and dwelling, and interests over the past several decades in regionalism all draw our attention to the ground on which we design and build. The allure of landscape is particularly acute in this country, however, where the uniqueness of flora and fauna is tempered by awareness of their fragility and of the impact of settlement on native ecosystems. The unresolved issue of Indigenous land rights fosters sensitivity to how other peoples have occupied, used and drawn meaning from the country in ways, presumably, less intrusive than those of our expanding suburbs.

Elsewhere, concerns of place-making and thoughts of being in the world suggest the value of immobility, fixity and traditions that grow from a single source or common ground. Tellingly, here, one finds evidence for the cultivation of transience, mobility and impermanence as part of the experience of living in Australia. Architects and students are likely to favour maps over final destinations, to frame their work by shadows rather than trees and to cover their surfaces with rust rather than paint. They build for a curious species, one that is always, already an outsider in its own homes.

These thoughts and efforts are derived from history as well as contemporary circumstances. Australian landscape has assumed such iconic value for designers because there is so much of it. For the entire period of British colonization, and even today, despite the ubiquity of air travel, we insisted and insist on thinking of it as so far away. For many there remains the longstanding view of the continent taken from the sea, an ensemble of coastlines seemingly with little else in between. The idea of terra nullius remains enshrined in a landscape of rusting wrecked ships and shearing sheds and abandoned mining towns: the detritus of colonial enterprise and source of design inspiration.

The idea of an empty land where you do things and put things has made us, like our colonial predecessors, witnesses to isolation. Cosmopolitan values and experiences governed thoughts on the landscape in the past and continue to do so today. As travel times have become largely irrelevant, geological time – like the Dreamtime – is for many a datum that measures the divide between nature and culture comprising a sense of identity. Efforts to identify a uniquely Australian culture are likely to be built not so much on urban typologies, topography or morphology, but on the suspicion (for some an article of faith) that our hold on the land is tenuous at best and our sense of ourselves fluid and changing – hence, the difficult task of making buildings appear the same. For this, rust comes in handy.

The Karijini National Park Visitors Centre in Western Australia by Woodhead International is an interesting exercise in contrived oxidation, which makes reference to landscape in an orthodox reverential way. Located in a region comprising some of the world’s oldest geological formations, the site has only recently been explored by the descendants of European settlers and exploited. Iron fills the air with dust and colours the local community and export facility at Port Hedland vivid red.

Constructed using weathered steel that matches the red earth it rests on, the plan of the building is said to be a “metaphoric goanna”. Notwithstanding such animistic references, the design is guided by a particular and familiar view of the land as a place of timelessness where buildings appear as organic and as the refinement of natural materials. The project brings to mind another, Massimiliano Fuksas’s design for the entrance to the cave paintings at Niaux, France (1988–93), which is likened to a prehistoric beast emerging from its lair. It too is made of rusting steel, though commanding a highly prominent position in a manner that would most likely be unacceptable here.

It is worth comparing the project for the Pilbarra visitors centre to the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA) in Melbourne, which deals with the uniqueness of place and the meaning of rust differently. Whereas the Visitors Centre, like Fuksas’s Musee des Graffiti, announces the place where cultural identity is born, the ACCA resists fixity. It turns in on itself to house culture as an ever-changing process. The project’s architect, Roger Wood, describes the building modestly, as conceptually simple: “It’s just a shed with a steel skin.”

Writers have noted the designer’s attempt to instil a sense of ephemerality in the project, describing how it resists a fixed reading of scale, eroding as one approaches like the weathering steel that covers it. Forms are both permeable and protective while the patina acquired by surfaces alludes to the faded red bricks of surrounding industrial buildings. Interiors are described in generic terms of spaces for events – for becoming, not being. Windows are not used, though light is strategically admitted through gaps or tears in the exterior wall surfaces.

The project has been likened to the work of Serra. Though celebrating industrial manufacture, the ACCA turns in on itself, as Sandra Kaji-O’Grady has written for Architecture Australia, offering little vantage point to survey the surrounding landscape of red brick factories and warehouses. Urbanity is contained within the centre, though through activities that occur there over time, not as a representation of the past.

The Karijini National Park Visitors Centre and the ACCA use rusting metal in different ways, reinforcing a pious regard for the two building sites. In other contexts or historical circumstances this would be manifest in the penitential piling of stone upon stone, but in Australia today piety is built on all that is valued as transitory in the “Australian experience”. It is built on a desire to “touch the ground lightly”, to call Murcutt to mind, that ultimately appropriates the land as a place of spiritual syncretism. At Karijini it is built from the rust that disappears into the earth while failing to stain the ground, being already the same colour. It is built from the language of primary elements, of ashes to ashes and dust to dust, oxide to oxide. It is the piety of hermits – or their admirers. It suggests a longing for timelessness that in another context would lead one to admire ancient ruins, white walls rising from a limestone headland or honey-coloured columns warmed by a Mediterranean sun. In Melbourne it is built from the rust of the everyday, the red of metal and bricks, factories and warehouses. It too fails to stain the earth, for the earth has already been marked by human enterprise. It is the piety of the entrepreneur and endless activity – the place of the coenobite. Given these two conceptions of landscape, facing both an empty, timeless land of star-spangled skies and a stockpile of natural resources to be consumed, the Australian experience is construed as unique.

It is with a curious mix of nostalgia for empty lands and bewilderment at their transformation through human activity that one approaches a landscape peopled by the final project considered here, the installation by Anthony Gormley on Lake Ballard in Western Australia. The site for Gormley’s project, completed in January 2003, is a 70-kilometre-square expanse of salt lake 500 kilometres from Perth. In a place so isolated and exposed that visitors must be extraordinarily committed to undertake the pilgrimage there, Gormley positioned 51 figures cast in carbonized steel (not self-weathering exactly, but very flaky) and set into the surface of the salt. The small town of Menzies, 55 kilometres away, provided models for Gormley, its residents allowing their bodies to be electronically scanned, digitized and then shrunk to a third of their natural volume. Features other than gender are left blank. Echoing familiar sentiments, one reviewer described how the “sighting of these disturbingly beautiful figures evokes thoughts of spirituality, of mankind’s endurance and his relationship to land and nation. As one staggers across the lake’s powdered surface, feet weighed down by salt deposits, heat mirages affect perception – are those figures on the horizon statues, or visitors or entirely imaginary?” ›› Gormley’s vision is a very familiar and very European one. His installation titled Inside Australia makes us all aliens in our own homes and casts landscape like the outback as places devoid of history though promising some kind of spiritual experience. If the Karijini Visitors Centre and the ACCA are pious acts, then these sculptures are votive figures and we – the few with the time, the money and the four-wheel drives to visit them – are the penitents.

By thinking about or through the landscape, the meanings that accrue to territory and the materials that compose it, we can not only design interesting buildings and sculpture, we can also question important things. Thoughts on the transience of human experience come to mind. In more familiar lands like the historically-charged landscapes of Europe, geology has been a force which suddenly and explosively intrudes on human history and scars urban landscapes with signs of rift and collapse. In Australia we are drawn to create our own unsteady foundations by acknowledging the precariousness of our hold on the land. The tragic, though for many visitors magnificent, remains of ancient buildings rent by seismic forces or degraded slowly over time are counterpoised here by an aesthetic formed by houses of cards and walls that rust.

DR WILLIAM TAYLOR IS ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA.