|

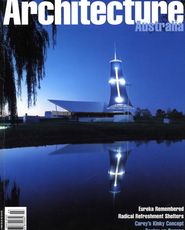

| Project Description In its design for the Eureka Centre, Cox Sanderson Ness adapted the key symbolic gestures of the original Stockade in an intentionally non-literal way. The original flag was flown horizontally but the new flag flies vertically from a 50 metre-high mast which soars on an angle (not as a vertical post) above the visitor pavilion. The mast penetrates the centre’s roof like a skewer and is tensioned across three truss beams and supported by cables. In plan, the architects recall the original Stockade hill (its exact location is still debated), with heavy masonry walls curving around the centre’s symbolic cores: an internal contemplation space and a commemorative lawn on the roof. To the north and west of those cores are exhibition, commercial, administration and commemorative facilities, including an outdoor café. The facade is distinguished by a bellied screen of horizontal oregon slats which evoke (again not literally) the Stockade’s original fence posts. Environmental benefits include passive ventilation through automated louvres at high and low levels, thermal insulation through subterranean spaces and masonry walls; evaporative cooling instead of air conditioning, and sunscreening via the slatted facade. Architect’s Statement by Patrick Ness Comment by Anthony Styant-Browne Site and building parti result in a highly ordered structure which provides a surprisingly open armature around which visitors and participants can construct their own interpretations of Eureka. A new ground plane creates an under (and over) world; the eastern extension of Sturt Street to the original monument is an axis of movement from below to above, and a line of division between major programmatic elements-café (south) and display/theatre genealogy (north); the contemplation space on this axis is an intersection with the commemorative axis from the genealogy tower to a small lake; and an undulating diagonal, the original Eureka ‘lead’, divides the site into Eurocentric (existing exotic planting) and Australian (indigenous plantings in ranks) domains. Derived from mapping of traces on the site, this structure sets up a number of oppositions which provide a lens through which the centre’s participants view the Eureka incident. |

|

Movement through the building is a choreography of axial and concentric patterns,

defined by clear paths and punctuated by strongly figural places-a superb built

example of Norberg-Schultz’s schemas of place, path and domain. Approached

axially across a forecourt, the entrance requires the visitor to execute a Lutyens

side step off axis into the foyer, from which he/she can resume an axial procession

up the stairs beside a narrow slot of water-paved space to the piano nobile of the

grassed gathering space; or make a hard left into the tall, annular space of the

temporary exhibition area with its inwardly canted walls-one glazed behind a

bulging timber slatted screen. The spaces have an attenuated, yet compressed

quality which one imagines is characteristic of underground architecture. Two

spaces in this suite are quite remarkable: the genealogy tower is a tall, truncated

trapezoidal pyramid penetrated by the flag mast, from which a path leads past a

sunken, gravelled courtyard, animated with shadows of the flag above, to the

contemplation space-

a silent, smooth-walled conical chamber containing a relic of the original Eureka

flag. Water plays softly at its floor’s perimeter, reflecting the play of light at the

ceiling. Those spaces given over to exhibition have been drained of architectural

presence through conversion into scenographic settings for multi-media

presentations of the Eureka experience-a commercial and popular necessity. This

is OK and part of offering a plurality of interpretations of Eureka. The Eureka Centre explores three different architectures simultaneously: the architecture of the earth through berm, curved concrete retaining wall, thick-walled top-lit cells; the architecture of the sky through sticky timber trusses and pergolas recalling mine vent scoops; and the architecture of flight through the flag’s light framework of struts and ties rigged like the wings of an old Tiger Moth aircraft. To pull this off is difficult but the architects succeed, despite some ragged seams here and there. Skewering through the building, the mast is at once a crucial connector and a foreign body violently penetrating the structure. This violation demands to be acknowledged but, at the highly charged junction of mast and roof, there is a penetration as perfunctory as a plumbing vent flashing. At the opening of the building on March 27, Premier Kennett (wisely declining to fire a cannon shot; sensitive to the issue of gun control), remarked on the meaning of the Eureka story to contemporary Australian culture and the role which would be played by the centre in focusing debate and interpretation of that event. On that brilliant, blue-skied day in the crowded gathering space, as the blue and white balloons were released into the sky, his words rang true. The architects of the Eureka Centre had established a profound sense of place and occasion. Tony Styant-Browne is the principal of Anthony Styant-Browne Architecture & Urban Design in Melbourne. Eureka Stockade Interpretive Centre,

Ballarat, Victoria | |