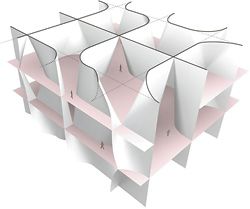

Art Museum Berkeley – the internal surfaces, with the chamfered grid highlighted on the uppermost plane.

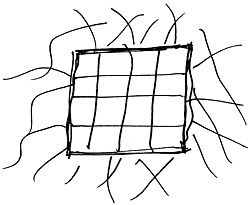

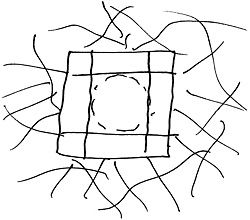

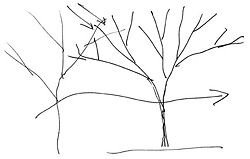

A. Dynamic order of the natural environment is interrupted by the imposition of architectural order.

B. Ito describes his Generative Order for architecture in relation to the adaptive growth of a tree that follows its own internal mechanisms but is also influenced by light, wind and surrounding conditions.

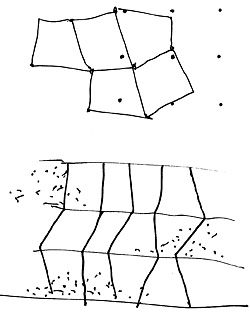

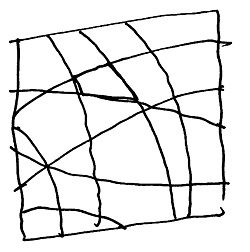

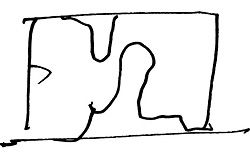

C. Random shifts from the grid across three floors generate a series of commercial spaces in an unbuilt proposal for a department store, maintaining the optimum volume between columns that increases sales (plan and section).

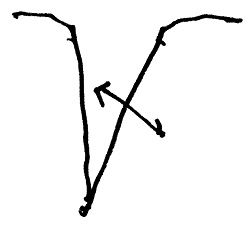

D. Vertical perforation of the cube through organic pylons in the Sendai Mediatheque, Sendai, Japan (plan and elevation).

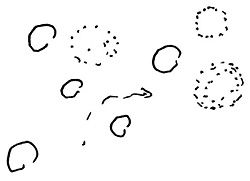

E. Plan detail of the study and media zones in the Sendai Mediatheque. Ito adds that in addition to non-prescribed activities, his staff noticed the adjacency of senior and teenager reading clubs led to a shift in fashion sense in the elderly patrons!

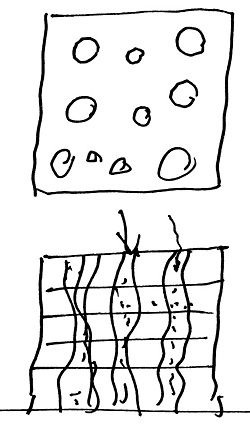

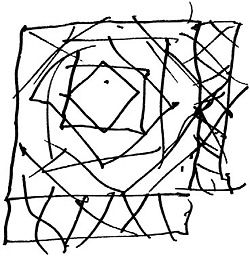

F. Incremental scale-and-rotation of the square in the temporary pavilion adjacent to the Serpentine Gallery, Hyde Park, London (plan).

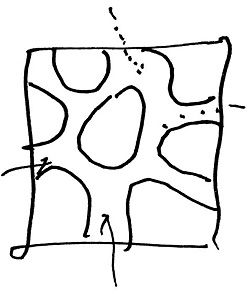

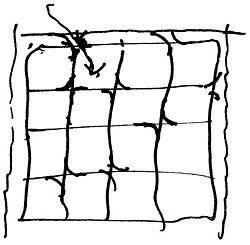

G. Alternating points in overlaid grids are pinned with an inner membrane, whereby separation of the floors creates volumetrically continuous surfaces in the Taichung Metropolitan Opera House, Taichung, Taiwan (plan).

Toyo Ito expressed some disbelief when I asked him to draw impromptu during a recent interview. Ito was in Sydney and Melbourne for the Australian Institute of Architects International Lecture Series and, as I expected, his drawings revealed some of the intricacies of his design motivations – in particular his idea that architecture might lead us to rediscover some of our “animal instincts”.

Ito’s first observation is that architecture’s role has been to place a rigid, geometric order within the dynamic and fluid order of the natural environment. At the urban scale, he argues that architecture and technology make us increasingly homogeneous, with our lives constrained by the forms around us. His first sketch shows two plans in which the fluid movement of people/nature is interrupted by the boundary of the cube (A). He argues that it is necessary for architecture to allow a more animalistic mode of inhabitation that is not restricted by the boundary.

To examine this idea one could ask: What are animal responses to order imposed from the outside? Biology and experimental psychology show that animal responses to artificially imposed order vary from modification of routine behaviour to the development of socially and biochemically manifested mental illnesses. Migration and increased exposure to disease also occur. In the long term, mutation and evolution and even extinction are outcomes that are neither positive nor negative if imposed order is there to stay. In the urban realm, Ito offers his analogy of the contemporary human as an urban Tarzan. While succumbing to ordered life imposed by the rationalist grid, freedom is experienced in the boundless jungle of communications technologies.

In Ito’s design concept of “Generative Order”, architecture responds like an organism among organisms and the environment influences the way growth adapts. Ito explains that architecture should be like a tree, which, although it has its own internal growth mechanisms, is shaped and formed by the context of available light, space, nutrients and airflow (B).

But Ito’s concept of generative order is not necessarily a useful metaphor for understanding his animal-boundary rationale. Though he uses the tree metaphor to describe his work, it appears that Ito’s “natural world” is not the biological or climatic world but the human culture of choice, decision and demand as demonstrated in the occupation of buildings. It is the collective spatial mind.

In this light, technology is the greater hidden force that places “order” on the environment. Indeed, all design products speak of a technological order, be it the order enabled by a fabrication method or the socio-cultural order prescribed by adoption of the new. In this way, design evolution is a series of order-generating stages and adaptation occurs in response to the technology of the time.

Curiously, Ito’s model of designing seems not one of adoption of the freedom of technology but one of resistance, of finding the animal through constraint. The drawings will explain.

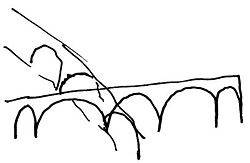

Sketches (C) to (J) are of Ito’s works, detailed in the captions, which show an implicit, step-by-step evolution in his oeuvre. Each building originates from a basic cube. From here, formal diversity and function are created by applying a consistent rule, which represents a controlled mutation of the modernist grid, appropriated to each contextual instance. Figure (C) illustrates how the pylons in an unrealized department store are randomly shifted from the grid across three floors to create a continually shifting multilayered space. In (G), the Taichung Metropolitan Opera House in Taiwan, alternating points in overlaid grids are pinned with an inner membrane such that separation of the floors creates an undulating, yet rigorous, intermediate surface within. In (F), (H) and I, the grid itself is twisted or fragmented, generating new spatial and structural solutions.

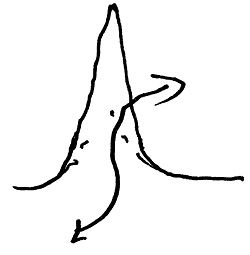

Although Ito explains he has no single guiding principle, his drawings suggest a set of projects based on the construction of algorithmic challenges that relinquish control from the grid. Even though he argues that a generative order should occur in the adaptation of the building, he clearly advocates a “psychological order” of movement through a building as the result of architectonic articulation. This idea of control-release is beautifully demonstrated in his most recent project, the Art Museum Berkeley (I),(J). Here a 4x4 grid is distorted at alternate intersections using curves, connecting diagonally located zones. The distortion is again alternated between floors such that the openings become triangulated in vertical space: some spaces are opened at the ground level, others at the ceiling height (J). The result is a precisely mutated modernist grid. The spaces created within this philosophy are incredible and inspire an elemental awe.

Ito’s buildings are technologically impressive. While concealing processes of constraint behind their spatial diversity, they overtly exhibit great feats of technological poise. Sendai Mediatheque, the Taichung Opera House and the Art Museum Berkeley are monumental expressions of technology.

The technologies Ito deploys are the same as any international starchitect today – digital casting in construction and computational modelling of force-form at play. Yet the aesthetic he achieves has a distinction not hindered by the freedom offered by technology. As Ito reveals in his lecture, innovation takes place within the very precise formwork created by his dedicated Japanese contractors. But without doubt such innovation is dependent on mechatronics innovation, dependent on computing innovation, dependent on mathematics innovation and so on. Architectural fabrication – like the tree – grows and adapts based on the state of surrounding innovation. It is both an actuator and a receptor of the larger technological paradigm.

Regardless of the powers enabled by this combination of dedication and milieu, Ito denies innovating for the sake of innovation. He reiterates that his main goal is to improve the freedom and comfort of the people inhabiting his buildings. But even with this rationale, he surely cannot deny that technology enables a new spatial order and potentially new behavioural order. Ito avoids the simple assumption that a freer geometry equates with freer movement. For him collective spatial behaviour is not a simple process of reversal to the primitive.

Perhaps a technological meme can run its course. Ito’s sketches suggest that the idea of rational-modernist order has gained enough evolutionary strength in our collective habits. From here even subtle variations in order allow a substantial shift towards a fluid inhabitation of the built environment. In this understanding, Ito’s mutation of the rationalist grid might slowly bring about an evolution towards “uninhibitionism” in space as a form of behavioural resistance to order. The animal instinct would then be a construction of architecture rather than a reversal based on complete geometric fluidity.

In passing discussion, Ito says that the Japanese as a culture are not particularly creative but that theirs is the skill to borrow and refine, calling it the talent of sophistication. In contrast, Ito claims that his work has no signature, no style, and does not aim for evolutionary refinement; every building is a new style, a new approach, with new challenges. Yet in these sketch-discussions, the rationale I see emerge is one of a highly controlled tactic of mutation of existing order. While each building appears formally distinct, there is a continuing logic of step-by-step permutation of the grid.

Perhaps for the same reason that technology allows the inhabitant of a homogeneous Japanese city a Tarzan-like release, Ito’s grid mutations are the architect’s expression of discrete, momentary release within a larger paradigm of submission – technological order. I wonder, is this the genius of resistance against a teleology of technological progress? Or is it the hidden obsession of a man who lives in one of the most invisibly controlled societies in the world?

Regardless – and without question – the results are extraordinary. Ito’s works are landmarks of architectural progress. There is no other conclusion: Creativity in design or in spatial inhabitation must be an act of resistance. This is the animal in us all.

H. Weaving of the grid to generate an intersecting arch and vault system in Tama Art University Library, Tama, Japan (axonometric detail and plan).

I. The chamfering of selected grid intersections, alternating over numerous levels, creates a diagonally splitting matrix volume in the Art Museum Berkeley (elevation).

I. The chamfering of selected grid intersections, alternating over numerous levels, creates a diagonally splitting matrix volume in the Art Museum Berkeley (plan).

J. Internal elevation detail of the angular voids created between gallery spaces by the chamfering on alternate floors in the Art Museum Berkeley.