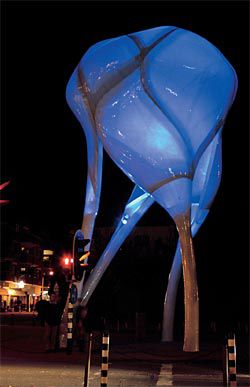

NOX’s D-Tower, 1999–2004, Doetinchem, charts the shifting moods of the city through changing lighting. The project is a collaboration with Rotterdam artist Q. S. Serafijn.

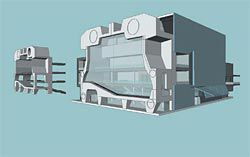

An example of FXV’s interest in ephemeral urbanism, this project was originally developed for the competition The Light at the End of the Tunnel, which sought creative and viable architectural ideas for restoring London’s railway viaducts. The component system is being developed into a deployable system for urban renewal.

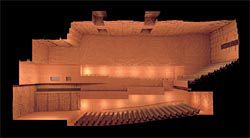

ARM’s project for the Melbourne Recital Centre houses the “precious” chamber within the “packaging” of the building.

Between the biennial Festival of Arts, and the Festival of Ideas in alternate years, talkfests on architecture and urbanism have become an established fixture of Adelaide’s cultural scene in recent years.

“Possible Worlds: The Architecture of Imagination”, a one-day symposium organized under the visual arts programme of the current (2006) cycle of the Adelaide Festival, was encouraging evidence that architecture remains, at least for the moment, “hot media” – to cite the still apposite notion of Marshall McLuhan, half a century on. Once again, in spite of almost no advertising, hundreds of interested citizens in addition to architectural students and practitioners were prepared to come out and immerse themselves for hours in the imagery and issues, if not the esoterica, of contemporary architectural discourse.

As curators Jennifer Harvey and Sean Pickersgill state, this symposium was “intended to provoke interest and speculation on the manner in which architecture can and will shape our lives in the future”. Futurology is at best a speculative exercise. But what was most striking about the actual discussion that ensued was the renewed insight it cast upon certain radically inventive strands of architectural thought and experiment in the past, and their enduring pertinence to the emerging new forms and orders of the urban present, if not the future.

Of the four keynote talks, the three morning speakers – Lars Spuybroek (principal of NOX Architects, Rotterdam), John Bell (director of FXV, London), and Neil Masterton (Ashton Raggatt McDougall) – represented the un-stated focus of the symposium on issues of digital mediation and invention in contemporary practice.

While focusing on seemingly arcane examples of early Renaissance religious paintings, the fourth speaker, Andrew Benjamin (UTS), addressed cognate issues in architectural representation. A final panel discussion, chaired by Justine Clark (editor, Architecture Australia), was initiated with a prepared response to the previous speakers by Sue Phillips (Phillips Pilkington Architects, Adelaide) in which local possibilities and implications of the day’s issues were explored.

Heralded as a master among contemporary digitally immersed architects and artists in Europe, Lars Spuybroek offered a disarmingly engaging introduction to the driving ideas, strategies and tactics of his work. Articulating a fundamental distinction that would be revisted variously through the course of the day, Spuybroek differentiated the time-honoured notion of the designer as a form-giver from his fascination with the notion of emergent order, or “epigenesis”.

In revealing accounts of a selection of his own art and architectural works, Spuybroek explored some of the challenges encountered in attempting to connect the possibilities of emergence and self-organization observable in other evocative examples of dynamic systems, such as bird flocks or soap bubbles, to the unique problems of architecture.

While the tools of digitally sophisticated designers today are new, Spuybroek reminded us that they only enable us to revisit old problems in a new light. Antoni Gaudi and Frei Otto, among others, had been there before.

Like Spuybroek, John Bell’s subsequent polemic on ephemeral architecture and the agency of the designer in the contemporary “city of bits” was underpinned with a reassuring historical perspective on the nature of the work and ideas at issue.

Championing Archigram and their situationist tactics as precursors to the emerging “cyborg urbanism” and “short-wave” dynamics of the way we actually live in cities today, Bell shared his profound appreciation in retrospect for the genuinely inventive and far-seeing futurism of these pre-digital pioneers of radical new forms of urban and social space.

The increasingly urban-scale design work of ARM of Melbourne proved an interesting foil for further demonstration and later discussion of many of the design strategies and tactics described by the previous two speakers. Speaking on behalf of the firm, Neil Masterton articulated a conscious creative tension in their work experimenting with “big things”, either as icons in themselves or as the occult objects/ideas that impress themselves on the “generic stuff” of building. This was illustrated memorably in ARM’s current project for the Melbourne Recital Centre, in which the section reveals the precious chamber of the concert hall itself inside the generic packing of the architectural superstructure.

Returning somewhat obliquely to the stated themes of the symposium – possible worlds and the architectural imagination – Andrew Benjamin brought the discussion back to fundamental aspects of architectural theory in the final formal talk of the day.

With the advent of the digital, he argued, we need to question the status of the architectural image, as part of the need for a renewal of architectural theory more generally. Marked by the contingency of its reception in time and place, the architectural image has an aleatory nature, or afterlife, which cannot be predicted, in the form-giving sense of a finite prescription for a predetermined architecture. The latent possibilities of such a projection can only emerge in real-time – as each of the earlier speakers had demonstrated through the contingent experience of experiment and practice.

Working at the intersection of theory, criticism and practice, John Bell offered some of the most compelling and potentially productive insights of the day, for this reviewer, with his critique of “long-wave” design and planning ideologies in the “short-wave” realities of contemporary urbanism. Moreover, Bell clearly attempted to address the actual brief of the symposium’s sponsor, the South Australian Government Department of Environment and Heritage, who had asked speakers to offer ideas on how architecture may be involved in a more sustainable way of thinking about environmental design.

Inadvertently perhaps, but unforgettably nevertheless, Bell’s nostalgic celebration of the ephemeral lightness of being of Archigram’s 1970s project for “Event City” offered a paradoxical answer. For a big country town such as Adelaide – which, for one month every two years, is transformed into the “Event City” without equal in this half of the globe – the bigness of the more metropolitan architecture and urbanism to which it has often aspired is simply not necessary, not to mention unsustainable. In a smarter, lighter world of technologically integrated environments designed to respond to and enrich the moment, not to shape the future irrevocably, it might just be possible to have one’s cake and eat it too.