Plan of Goiânia by Attilio Corrêa Lima, with revisions by Armando de Godoy, 1934. Courtesy Christopher Vernon.

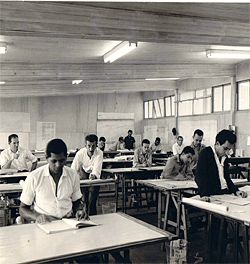

Oscar Niemeyer’s studio at Brasilia, 1958. Reuben Lane is at the far left and Niemeyer is visible at the back of the studio, leaning over a drafting board. Courtesy Reuben Lane.

Christopher Vernon reflects on the long history of engagement between Australia and Brazil.

Browsing the shelves of an Adelaide out-of-print bookshop years ago, I happened across a copy of Brazil Builds: Architecture New and Old 1652–1942 by Philip L. Goodwin; long an admirer of Brazilian modernism, I promptly bought it. For me, this was a surprising find. I was certainly aware that Brazil had sensationalized architectural circles in the Americas, beginning in 1939 with its New York World’s Fair pavilion and accelerated by the Museum of Modern Art’s 1943 exhibition, the catalogue for which I now held in my hands. Up until the time of my Adelaide purchase, however, I had seldom considered Brazil’s Australian impact; now with a catalyst to do so, I soon uncovered a rich exchange between the two Southern Hemisphere nations.

Brazil entered Australia’s architectural imagination via a town planning portal, at least as early as 1914. That year, with the enterprise to build a new national capital pervading the professional climate, George Taylor published Town Planning for Australia. He directed attention across the Pacific to Brazil. In 1894, the state of Minas Gerais, he reported, removed its capital from Ouro Preto and began constructing another on “virgin land”, Belo Horizonte (Beautiful Horizon). Only a decade later, some thirty thousand people resided in the city; it had also gained government and public edifices, “electric light, trams, theatres and other luxuries available”. Envisaging a similar future for germinal Canberra, Taylor offered the Brazilian example as overseas validation for Australia’s decision. Taylor may not have been the first Australian to scrutinize the capital; it was possibly known earlier to at least one Canberra competitor. At Belo Horizonte, urbanist Aarão Reis organized its streets on a chequerboard and then superimposed another grid of boulevards at forty-five degrees to the first, creating a radial plan. In his Canberra submission, Melbourne architect Alexander Macdonald also employed this technique. There was even an entry by an Australian living in Paraguay, perhaps a lingering refugee from one of the two utopian colonies of Australians there. By 1914, Latin America, if not specifically Brazil, was likely already well established in Australia’s ken.

For Australia and Brazil alike, 1927 was a portentous year. That May, Australia’s Parliament finally opened in Canberra. On the day, the Canberra Times trumpeted Brazil’s similar decision to erect a purpose-built capital, leaving Rio de Janeiro “to prosper as a commercial city”. Brasilia, however, would wait another three decades for a political champion to make it reality. Parliament’s opening also renewed media attention to Walter and Marion Griffin’s city plan. Only months later, two Latin American journals reproduced their layout, one heralding it “the most splendid lesson for us in modern urbanism”. With such accounts as its export conduit, the Griffins’ design would not go unnoticed in Brazil. In 1927 the Brazilian Government retained French urbanist Donat-Alfred Agache to orchestrate monumental design interventions at Rio de Janeiro. As with Canberra, that city gains grandeur not from concentrations of architectural magnificence, but from its spectacular landscape setting. Nonetheless, Agache was now to blast grand boulevards through and new building sites within its mountainous terrain. He was earlier, in an ethereal coincidence, one of the Griffins’ Canberra competition rivals, placed third in the contest. Polygonal geometries pervade his Rio de Janeiro proposals, suggesting that the Frenchman took backwards glances at the prize-winning Australian plan. In 1933, six years after Canberra’s Latin American surface, Brazil’s state of Goiás followed Minas Gerais’ lead and began a new capital de novo, named Goiânia. The nucleus of its layout distinctly resembles Canberra’s, which hardly seems a coincidence.

Australia and Brazil converged at the 1939 World’s Fair. There, like their Brazilian counterparts, architects Stephenson and Turner assimilated a modernist vocabulary for Australia’s pavilion, partly to assert an identity independent of the country’s status as one of Great Britain’s dominions. Unlike Brazil’s freestanding structure, however, the “Australian Pavilion” was one in name only; it was actually an interior installation within an American-designed building. Nonetheless, Australian Thomas O’Mahony, in New York overseeing the project’s construction, would not have overlooked Lucio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer’s Brazilian pavilion rising nearby.

In 1945, furthering the southern dialogue, Walter Bunning published Homes in the Sun. Advocating climatically responsive architecture, Bunning illustrated two Brazilian examples. A São Paulo courtyard-plan house, 1941, by expatriate architect Bernard Rudofsky, for Bunning, perfectly demonstrated “opening out a house to allow good air circulation in a hot climate”. He also reproduced the iconic Ministry of Education and Health Building, designed by a team of Brazilian architects, including Costa and Niemeyer, in consultation with Le Corbusier, 1937. The adjustable louvres cladding the edifice compelled its inclusion; excluding sunlight with such devices was, Bunning believed, also apt for Australia. Later, Stephen Trotter’s climatic concerns led him to Brazil, which featured in his 1963 study Cities in the Sun.

In 1956, Brazil elected Juscelino Kubitschek its President. Branding his campaign “Fifty Years of Progress in Five”, Kubitschek pledged to finally realize Brazil’s centuries-old capital vision. Although Brasilia’s story is now legendary, we must revisit it briefly to discern the project’s lesser-known Australian implications. Also in 1956, underpinning the Brasilia enterprise, diplomat J. O. de Meira Penna made a global study of national capitals, later published as Quando mudam as capitais (When capitals are moved), 1958; he included Canberra within his scrutiny, again bringing it to local attention. Brazil, like Australia, opted to secure its capital’s design via competition; however, Brazil limited its contest to nationals. British town planner William Holford served as its international adjudicator. In March 1957, Lucio Costa’s plan emerged victorious. Holford travelled to Canberra that June to give expert advice on its development. Brasilia was now poised to impact the Australian capital.

The most dramatic built outcome of Holford’s consultancy was Canberra’s much-anticipated lake, 1964, a central component of the Griffins’ plan. Holford’s water body, however, encapsulated prominent departure: eschewing the geometric clarity originally envisaged for its central basins, the new lake’s margins metamorphosed irregularly. Moreover, Holford believed its banks to be the ideal locus for Australia’s yet-to-be-constructed permanent parliament buildings. This view was informed not by the Griffins’ thinking, but by his own Brazilian experience. At Brasilia, Costa concentrated the seats of legislative, executive and judiciary powers together in the Praça dos Três Poderes (Square of the Three Powers), at one end of his Eixo Monumental (Monumental Axis), near the city’s artificial lake. Taking this government assemblage as precedent, Holford proposed an Australian “lakeside parliament”. This varied dramatically from the Griffins’ design; abandoning their original elevated site, Holford shifted the parliamentary complex down the city’s central land axis to the lake shore. Implementation of the scheme began in 1958; however, it was abandoned a decade later. One survivor of Holford’s initiative is the National Library of Australia, whose principal architect was Walter Bunning. Brazil had already captured Bunning’s imagination. If Holford’s lakeside parliament resonates with Costa’s Praça dos Três Poderes, then Bunning’s library does no less so with Niemeyer’s Palácio do Planalto (Palace of the Highlands or Presidential Palace), 1958, and Palace of the Supreme Court, 1958.

When Brasilia opened in 1960, Oscar Niemeyer had begun to emerge as Brazilian modernism’s champion; he even garnered Australian mention that year in Robin Boyd’s The Australian Ugliness. Today, Niemeyer’s repute has burgeoned. Indeed, prior to speaking at Brasilia, I was cautioned to choose my words carefully when mentioning the now-heroic architect. In Australia it is conventional wisdom that the late Harry Seidler worked for Niemeyer. He was not, however, the only Australian to do so. Lecturing on Australian and Brazilian connections in Canberra last May, I was approached afterwards by Reuben Lane. In a revelation akin to my Adelaide discovery, the Sydney architect informed me that he, too, was once in Niemeyer’s employ. Lane, while still a student, was seduced by the Brazilian’s “lyrical free forming designs” and vowed to work for him upon graduation. In 1958 he did just that, working on site at Brasilia, no less.

The landscape preoccupation that pervades Australian and Brazilian notions of national identity connects the two countries, and their respective national capitals demonstrate this. Australian mystique about the bush emerged in the early twentieth century. No longer was it regarded as a sombre or “haunting” obstacle to settlement. At Canberra, the Griffins allowed the site’s physical attributes, its hill summits and watercourse, to determine their cross-axial scheme’s alignments. Through this structural dialogue, their design monumentalized the indigenous landscape. Like the bush’s Australian status, the jungle is embedded within Brazil’s cultural psyche. In Brasilia’s time, the jungle was seen as uncivilized, the antithesis of culture. Consequently, one of the first manoeuvres at Brasilia was to eradicate its site’s cerrado vegetal mantle. Although this was later replaced partly with native plantings, many of these are heavily manicured so as to obscure their local origin. As in Australia, landscape appreciation came later. Brasilia has now reached the half-century mark and Canberra’s centenary is fast approaching. Despite time’s passage, there is a final, enduring perception linking the two capitals. They are each viewed locally by many as surreal, artificial cities – Brasilia is “un-Brazilian” and Canberra “un-Australian”.

Christopher Vernon is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Visual Arts at the University of Western Australia. This essay is derived from his opening night lecture for the exhibition Connections: Australia and Brazil at the