LIVING THE MODERN_AUSTRALIAN ARCHITECTURE

“A swarm of colourful fish.” Suspended illuminated panels present the work of 25 Australian practices. Photograph Anke Sademann.

Bombala Farmhouse, NSW, 1998, by Collins and Turner. Photograph Ross Honeysett.

Dock 5, Melbourne, 2007, by John Wardle Architects in association with Hassell. Photograph John Gollings.

Old House, Richmond, Victoria, 2006, by Jackson Clements Burrows. Photograph John Gollings.

Leederville, WA, 1999, by Donaldson + Warn. Photograph Martin Farquharson.

Foxground Residence, NSW, 2005, by Studio Internationale. Photograph Martin van der Wal.

Dome House, Hawthorn, Victoria, 2004, by McBride Charles Ryan. Photograph John Gollings.

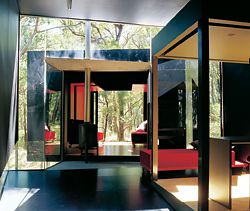

The Black House, Red Hill, Victoria, 2002, by David Luck Architecture. Photograph Catherine Tremayne.

Liverpool Crescent House, Hobart, Tasmania, 2005, by Terroir. Photograph Ray Joyce.

International in tradition, local in flavour. Sarah Quigley considers the exhibition at the Deutsches Architektur Zentrum.

Berlin-Mitte has become a pretty toney neighbourhood, but the German Centre for Architecture is on its shabby outskirts, far from the glass-fronted galleries and glossy stores. Situated between old Stalinist apartment blocks and Turkish car yards, in an old brick factory that used to manufacture soap, it’s the temporary home to a large-scale exhibition on Australian modern architecture.

After the chilly autumn weather outside, the exhibition hall seems full of warmth and light – not least because most of the photographs feature the brilliant blue skies associated with Australia. The white walls, too, are splashed with blue, with a painted time line stretching around the room, detailing the history of Modernism.

Living the Modern_Australian Architecture features 48 buildings from 25 practices, both established and emerging. By focusing on residential architecture, the exhibition highlights the way that Australian architects first imported Modernist European concepts and then modified them, creating a uniquely progressive architecture. This “adventuresome” spirit literally shines through – all projects have been exhibited on floating white ovals lit from within.

Curators Claudia Perren and Kristien Ring describe the display concept as a “swarm of colorful fish”, but in fact the suspended illuminated displays look more like clouds, or zeppelins. All three images are appropriate enough for Australian architecture, conjuring up bold and progressive design coupled with an unswerving consideration of environment. Photographs, texts and plans have been drafted into six subcategories: Minimal, Sculptural, Frames, Interaction, Landscape, and East/West.

Minimalism is an obvious starting point, for the reduction of form has long been an indicator of Modernism. Mies van der Rohe’s maxim “Less is more” is dramatically realized in buildings such as Ian Moore Architects’ Air tower on Queensland’s Gold Coast. The slender dual bodies soar to 37 stories, maximizing ocean views; but their stark, exposed forms have been designed with comfort in mind – deeply recessed balconies minimize heat gain, while glazed floor-to-ceiling windows allow for maximum natural light.

A minimalist example at the other end of the scale is the Collins and Turner Farmhouse in New South Wales. This low dwelling – two adjoining rectangles of steel, corrugated iron, aluminium and glass – crouches on its stark, dry landscape like a grasshopper. At home with its environment, utterly modern in appearance, it’s unmistakably Australian in its functionality but universal in its use of abstract form.

The low, sleek lines of Studio Internationale’s Foxground Residence (NSW) reveal a similar deference to both location and Modernist tradition – as do David Langston-Jones’s Queensland and NSW houses. The adaptation of minimalist form is seen to be subtle but crucial, due to Australia’s harsh natural environment and growing environmental concerns.

The “Sculptural” projects appear in sharp contrast. Curves replace angles; flat roofs are ousted by asymmetry. Here the increasingly popular fusion of art and architecture becomes most apparent: quite literally in the case of Fender Katsalidis’ Republic Tower in Melbourne, with a street-level wall dedicated to the display of public art. More subliminal connections emerge in McBride Charles Ryan’s Dome House in Victoria, whose beautifully unexpected, half-fractured exterior alludes to the work of American artist Gordon Matta-Clark.

Also in Victoria, the brutal concrete exterior of Wood Marsh’s Gottlieb House nods to the stark monumental forms favoured by artist Richard Serra, yet its elegant, spacious interiors allow an unexpected interplay of natural light and shadow. These are the kinds of building that invoke Le Corbusier’s words: “By the use of inert material, and starting from conditions more or less utilitarian, you have established certain relationships which have aroused my emotions.”

After the clear-cut Minimal and Sculptural categories, those of “Frame” and “Interaction” appear arbitrary, and a little whimsical. “Frame” focuses on the way that steel-and-glass constructions can let “interior and exterior spaces overlap and melt together”. Yet the selected buildings, from John Wardle’s towering Dock 5 in Melbourne to Jackson Clements Burrows’ cleverly disguised “Old House” (which employs a photographic facade of the original house), seem to highlight Australian ingenuity more than anything else. The same is true of the Interaction category. The curatorial aim here is to highlight “interaction between architecture and humans, architecture and nature, nature and culture, public and private, interior and exterior, light and shadow, void and solid, past, present and future” – which reads like a manifesto for architects from almost any era, anywhere. Regardless of textual waffle, the houses are stunning: Kerstin Thompson’s arrowed black house at Lake Connewarre, with its “folded” roof; Donaldson + Warn’s Leederville residence, inspired by a small disused foundry.

With Landscape and East/West, the focus of the show returns more firmly and confidently to assert the truly modern approach of Australian architecture. A quotation from Glenn Murcutt highlights the environmental challenges: “There is an overriding horizontality … The sunlight is so intense … that it separates and isolates objects.” And the featured houses show innovative solutions that are placing Australia’s architects on an international map. Denton Corker Marshall’s house on Phillip Island, and their Sheep Farm House in Kyneton, have both been partially sunken into the ground. In spite of their stunningly modern designs, both appear to have grown up from the earth itself. Terroir’s rectangular houses on steep, tree-covered sites in Tasmania display a similar fusion of bold design and environmental sensitivity.

The East/West category provides a perfect conclusion, for this most clearly points out the specific and divided nature of Australian architecture. Modernism, like many other international movements, has been transformed in its transference – from Old to New Worlds, from the West to Asia, and even from the east to west coasts of Australia. Some of the most strikingly visual houses are displayed here. Lippmann Associates’ Butterfly House, a delicate curved white structure above Sydney Harbour, was built for a client with feng shui beliefs who requested “no straight lines”. David Luck’s Black House and White House (one rural, one urban) employ simple Miesian designs to jaw-dropping effect.

To wander through the cluster of display “fish” is to gain a sense of the extreme innovation at play in contemporary Australian architecture. The Modernist link is a perfect theoretical starting point for a show that’s international in tradition but has a decidedly local flavour. The issues at the heart of Australian architecture today – an independent and original expression of Modernism, site-specific design and sustainable solutions – are catching the attention of the wider world.

Dr Sarah Quigley is a novelist, columnist and critic who has been based in Berlin for the past seven years.

Living the Modern_Australian Architecture was at DAZ/Deutsches Architektur Zentrum 12 September – 11 November 2007.