Photographer Paul Pavlou, photomedia manager, UTS.

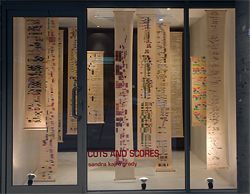

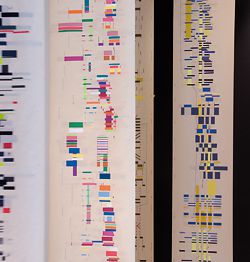

Looking into the DAB Lab gallery. The rolls of woven paper are suspended vertically, creating an environment of overlapping screens.

Jack o Lantern (detail).

Monterey Cliffs (detail).

Details of the hanging installation.

Winter Bird (detail).

Veronica’s Sash (detail).

Playing colour. Olivia Hyde reviews Sandra Kaji-O’Grady’s recent exhibition at the DAB Lab.

The DAB Lab is more of a shopfront than a gallery – a small space, a few metres across and the same in depth. It overlooks the raised courtyard of the Design, Architecture and Building faculty of UTS, next to the cafe. Directed by Aanya Roennfeldt, the gallery is intended to provide managerial assistance and a public showcase for faculty and postgraduate work. As such, it operates as a means to peer review creative or project-driven research work. Each exhibition is subject to curatorial selection by peers, an exegesis and a catalogue that includes an associated critical review of the work – in this case by Naomi Stead.

Cuts and Scores, Sandra Kaji-O’Grady’s installation in this space, derives in part from her doctoral study of serialism in architecture, art and music, which led to an interest in the American composer Conlon Nancarrow. Nancarrow, a committed socialist, went into self-exile in Mexico in the 1940s after he was refused a US passport for his political sympathies. Faced with a lifetime of musical isolation, he ordered an Ampico Reproducing Piano – a pianola – and the required hole punching equipment to allow him to create self-performing music. Though to some extent a reaction to adversity, the system also allowed him to explore his own interests: “As long as I’ve been writing music I’ve been dreaming of getting rid of the performers.” Nancarrow’s compositions explore the idea of impossible music – “extreme scores”, as one writer put it – music of such polyrhythmic complexity that it is beyond the range of the human performer (though in recent years various pianists have risen to the challenge). It is unclear to what extent Nancarrow’s compositions were a surprise to him, visual compositions that revealed their true musical face only when “played”. Certainly they are not random and many of the devices appear both visual and musical in intent – the impossibly fast glissando or oversized chord, for example. For Kaji-O’Grady, though, his work was of interest specifically for its cultural ambitions as an artistic process over which the artist has limited control, and for its potential to speak of the overlap between the visual and the musical arts. A selection of Nancarrow’s polyphonic “post performer” music was played at the opening of the exhibition.

In Cuts and Scores two largely extinct notational systems – one of colour, one of sound – are brought together. The first is the Dulux Colour Specifier, the second a series of pianola rolls (Nancarrow’s work inspired Kaji-O’Grady to start a collection). The pages of the colour specifier have been sliced into strips and bands (cuts) and woven into the perforations of the pianola scores. The results have an obsessive and inscrutable quality. Sometimes there appears to be a strong conceptual strategy – the width of the bands emulates the pianola perforations while moving from one hue to another. At other times the relationship is more instinctual. Adding to the inscrutability, the titles of each roll – Winter Bird, Monterey Cliffs – hint at a romantic descriptive intent but transpire to be names from the Dulux paint sample range. The rolls have been suspended vertically within the gallery, creating a spatial environment of overlapping screens. Given Kaji-O’Grady’s interest in Nancarrow and the systems of serialism, the exhibit suggests, to this viewer at least, the beginnings of a long, fruitful and somewhat esoteric exploration of the possibilities of “playing” colour.

This is the ninth exhibit at the DAB Lab research gallery since its inception in November 2006. So what is research in this context? Traditionally one might describe research as any practice that adds to a body of knowledge. Means differ across fields. “Research” as a word tends to be linked with “development”, “R and D”, and, as such, to the sciences and the generation of explicit results through experimentation, such as products. In the humanities the term “scholarship” is more traditional. Scholarship implies something more like the immersion of an individual in a subject – a vocation. In areas such as the fine arts, architecture and design, the terms research and scholarship sit uneasily. Excepting historical, theoretical or technological undertakings within the field, the principal means of generating knowledge within these areas are through practice, by practitioners. In fact, it was the energetic rejection of the academy by artists of the early twentieth century that led to the vast changes in the scope and understanding of art practice that have taken place since. For architecture the relationship is perhaps most confused of all, given architecture’s slippery identity – neither science nor humanity nor art – but in some regards all three. Can a work of architecture be research? Does it add to a body of knowledge?

To some extent this is a moot point, but as soon as the creative schools become subject to the systems and structures of universities, such anomalies arise. It’s interesting to note, however, that terminology and credentialism aside, much of the most provocative and generative project-based architectural research of the last twenty years has come out of the largely independent schools: the Architectural Association in London, the Cooper Union in New York, SciArc in LA. In all cases a culture emerged under the patronage of a strong leading figure of creative scholarly enquiry through available means. Discussion and debate flourished. Studio teaching, the exploration of representational systems, competitions, exhibitions and installation-scaled work, along with publication, flourished as media for architectural experimentation, exploring unusual cross-disciplinary relationships and pushing at the boundaries of what constituted the architectural project. Starting in the late 80s, these schools led the way in expanding the realm of architectural practice and opened up new ways of thinking about the potential of the project in architecture.

Towards the end of his life, Nancarrow and his work emerged into the limelight. He was feted, awarded large bursaries and invited to tour widely. The DAB Lab may be a small start, but if the recent and noticeable increase in energy over at the UTS architecture faculty is something to go by, let’s hope it too is the start of something bigger.

Olivia Hyde is currently teaching final year design at UNSW and is an associate at Bligh Voller Nield in Sydney. She studied architecture at the Bartlett School in London and is co-coordinator of the Urban Islands international design workshop.

www.urbanislands.info