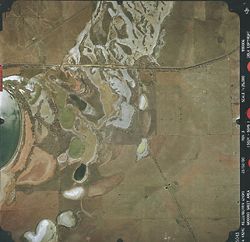

Satellite image Perth to Kalgoorlie, showing the Goldfields Water Supply Pipeline.

Aerial photograph and photomontage of Baandee.

Wheatbelt sanctuary site drawing.

The uncoiling, recoiling perceptual model, Speed_Space.

Overviews of the exhibition at the Holmes à Court Gallery. Earlier projects lead up to the perceptual model, with photographic studies of each Wheatbelt town on the walls.

Narelle Yabuka considers Speed_Space – Architecture, Landscape and Perceptual Horizons, by Stephen Neille.

Western Australia has always been a fertile playing ground for tough entrepreneurs, and its history is dominated by tales of male strength – in farming, industry and mining. As with the eastern two-thirds of the country, a “pioneering” mentality has dominated both non-Indigenous events and the construction of post-settlement history in WA. Prominent WA historian Tom Stannage has been one to question the idea of the “pioneer”, as it describes the serving of private interests first and last, rather than contributing to a common good.1 The PhD work of Stephen Neille (architect and senior lecturer at Curtin University of Technology), exhibited at East Perth’s Holmes à Court Gallery, questions architectural pioneering at WA’s greatest single-site project – the Wheatbelt region.

This area is twice the size of Tasmania, and could be looked on as an ultimate expression of pioneer thinking. When observed via aerial or satellite photography, the region displays a pixelated quality – not the result of poor photographic resolution, but of the domineering geometry of agricultural land ownership. A noticeable aberration is a line that slices through the pixels, snaking from Mundaring Weir in Perth’s hills to Kalgoorlie, and joining dot-like townships along its route. C. Y. O’Connor’s engineering feat, the Goldfields Water Supply Pipeline, is flanked by a road that speeds unrelentingly past the vast and fatigued tract of fictitious nature composing the Wheatbelt, and through a string of towns in various stages of survival, some prospering but most degrading.

The absurdity of the physical condition of the region has fascinated Neille for some years. In it he sees an environment that is falling apart, where landscape, hope and rational exploitation are disappearing, and nature has been exceeded. In the Wheatbelt’s surface, the sense of overbearing land exhaustion is evident. The surface, says Neille, “records our continuing need to build human habitat and our continuing lack of regard for a land undergoing collapse.” If architecture could play some role for the “common good” here, how might it be conceived, and how might it indeed address and exist within a vast site of saturated emptiness? How might architectural production surpass the pioneering mentality that has fatigued the land and arguably run its course?

Site often plays a determining role in the outcome of architectural work. Neille’s exploration of the constructed Wheatbelt site began with his 1998 Master of Architecture project, the Rambler’s Gallery, and the Big Journey/Small Buildings project of 2000, the latter conceived with Stephen Parkin. The Rambler’s Gallery drew on seven spatial typologies to create seven double-skinned gallery pavilions, which appear to create a whole pavilion when seen from the road. The architectural object was perceived as a go-between, straddling site and perception. The Big Journey/Small Buildings project invited twenty architect/educators associated with the university to create a constellation of speculative architectural projects – based in the towns located along the pipeline – on the themes of site and place, architecture and distance, and architecture and landscape. For Neille there remained, however, the nagging problem of context being inadequately addressed; the problematic reality of the physical locations was rarely dealt with. The solution to the problems was not, perhaps, the making of more projects in the landscape – a typically pioneering attitude. Rather, it may lie in the altering of human will – a shift in the perception of and approach to landscape.

Thus, his PhD research by project began and ended with the triangular relationship between human perception, architectural idea making and constructed landscapes. It concerned itself with documenting and searching for a new perception of the experience of the Wheatbelt. It asked, what aspect of reality could be exposed in such a way that it might affect our experience of architecture and landscape, affect our poetic intelligence? What kind of exposure might affect our re-imagining of site and therefore lead to the achievement of new architectural work? How might the observer of site realize a closer approximation of the truthful landscape?

The culminating result was the perceptual model Speed_Space – an uncoiling and recoiling muse that shows architectural experience to be a self-made constellation acting as a force of imagining. The line along the Goldfields Water Supply Pipeline was considered as an experiential sequence. The towns spread along it were recorded photographically and the photographs cut into the segments of a sphere that coils to overlap the separate parts into a single whole – a holistic memory of moments on the journey through the Wheatbelt. Speed_Space encourages wholeness of perception as a driver for architectural thinking, prompting speculation about the recurring conditions of fatigue evident in the site – a recoiling from the experience of exceeding nature.

The exhibited Speed_Space model occupied an unobtrusive yet culminating position in the Holmes à Court Gallery, preceded by earlier projects and circumscribed by walls hung with photographic studies of each Wheatbelt town. Aerial photographs and monochromatic photomontages appropriately prevented a direct “reading” of the physical conditions of the towns.

This showing of academic work in a commercial gallery closely followed the staging of Australia’s Venice Biennale show in the same space. Curtin’s Professor Geoff Warn (of Donaldson + Warn, Architects) was instrumental in securing showings for both exhibitions, and the Holmes à Court Gallery has demonstrated an encouraging commitment to establishing a greater community dialogue on cultural issues. Both exhibitions were well attended – perhaps a sign that Perth audiences are keen to enter a renewed engagement with architecture.

1. C. T. Stannage, Western Australia’s Heritage: The Pioneer Myth (Perth: UWA University Extension, 1985).

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Jan 2008

Words:

Narelle Yabuka

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2008