Dianne Peacock considers a recent exhibition and book on Howard Arkley, which invites us to look anew at the place where most Australians live.

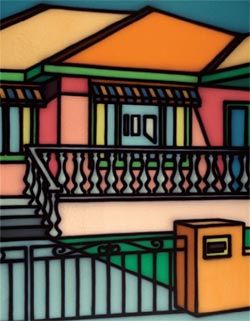

Howard Arkley, Theatrical Facade, 1996. Parliament House Collection, Canberra.

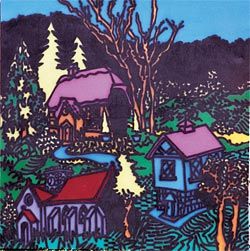

Howard Arkley, Tudor Village, 1986. Copyright courtesy of The Estate of Howard Arkley. Licensed by Kalli Rolfe Contemporary Art.

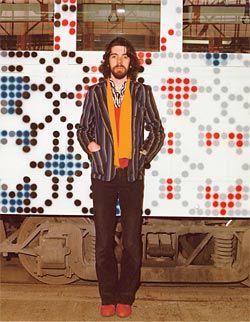

Howard Arkley, Metallic, 1981. State Art Collection, Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth.

Howard Arkley in front of his Tram no. 384, 1980. Howard Arkley Archive. Copyright courtesy of The Estate of Howard Arkley. Licensed by Kalli Rolfe Contemporary Art.

Howard Arkley, 1951–1999, transformed our vision of suburbia with his airbrush paintings of its houses. Pop aesthetics and a celebratory attitude contribute to their popular appeal. At once domestic and heroic in character, Arkley’s houses do not lack grandeur. Serious attention is given to the decorative, the fastidious and the display of pattern and material. Does Arkley’s work offer architecture a way into the suburbs?

Arkley’s houses offer nuanced and contradictory readings of suburbia through an ambivalent and lively relationship with the suburbs, a relationship that Arkley himself sustained through art practice and lived experience. The heavy black airbrush line characteristic of the house paintings leaves a thin haze of spray over the edges of the coloured areas it borders. This heightens their luminosity and produces the effect of heat haze, where, for instance, a roofline is set against a white cloud, or a yellow wall shimmers next to darker, shaded walls. Every element of house and garden is contained by this outline. Heat and glare, deserted streets with trimmed lawns; the suburbs are also boring and stifling, and the suburban home a symbol of middle-class values in a utopia of home ownership. The airbrush carries commercial rather than high art associations, and stencilling aids production of multiple images as pattern. There are parallels here with the suburban house, whose designs are repeatable, while each is different from its neighbour. Commerce, display, skill and repetition play a large part in their making.

An extensive touring exhibition curated by Jason Smith of the National Gallery of Victoria and a new monograph, Carnival in Suburbia: The Art of Howard Arkley by John Gregory, provide broad surveys of Arkley’s work and its subject matter – of which the suburban house forms only a part. The reader benefits from Gregory’s privileged access to Arkley’s archive – a chapter on source material reveals newspaper real estate advertisements and 1970s US decorator manuals, among diverse pop cultural and art historical sources and the artist’s own photographs of suburban elements. Titles of the suburban house and interior paintings often reflect these sources: Modern OYO Flats, Cosy Clinker and Deluxe Setting. Spartan Space (Homage to De Stijl), 1992, references Gerrit Rietveld’s Schroder House of 1924.

Postmodernism’s use of appropriation, its collapse of high and low culture, its use of irony and layered meaning are more than evident in the work of Howard Arkley. His practice developed in the milieu of the punk and feminist movements, and amid serious discussions and interest from peers.1 Arkley’s early black-and-white airbrush works, which open the exhibition, are subtle constructions: a revelation to viewers familiar only with his suburban paintings. Feminism offered artists a context in which to explore decorative and ornamental traditions, and while Gregory questions this influence, these traditions were, at least, taken seriously. The resulting body of work included the painting of Melbourne Tram no. 384, 1980, and the geometric compositions Disco and Metallic, both 1981.

The success of the large-scale Primitive, 1981, teeming with irreverent cartoon-like figures drawn from the artist’s visual diaries, initiated Arkley’s move into figuration and, from there, to the creation of iconic works. Primitive was recovered and restored for the exhibition. Its title, as we are informed by numerous references, derives from a song by The Cramps (but, I feel compelled to add, this song was originally by New York garage band The Groupies, 1966).

Arkley’s collaboration with Juan Davila on a series of interior tableaux combining paintings with painted objects, Blue Chip Instant Decorator: A Room, 1991–92, is included in the exhibition. An earlier collaborative project, Artists and Architects ’86, paired Arkley with Howard Raggatt.2 The pair worked separately, after agreeing on the site of the encounter: Melbourne’s Model Tudor Village. This abandoned utopia proved fertile ground for Arkley, who, after visiting the site on a stormy night, produced the spooky Tudor Village paintings of 1986.

John Gregory recalled discussing with Arkley the prospect of painting an actual house. While Arkley liked the idea, the project never eventuated. But perhaps it resonates in Cassandra Complex’s richly patterned Great Smith Aussie Home of 2006. According to the architect, the birthplace of this house is “a complex leafy electric disco”. And the house wanted “to add layers of space to time, to make time bigger through rich reverberations of two-dimensional surfaces”. The house features patterned ornamentation to selected external and interior surfaces. A stencilled pattern of gold bunnies and other creatures adapted from Little Golden Books adorns the main entrance. Other rabbit figures are abstracted to form a pattern cut into stainless steel screens. Edges here are precise, screen patterns are laser-cut, there is a high level of finish and pattern is balanced by relatively plain surfaces. There is intensity and the potential, in given light conditions, for the screen patterns to dance, disco-like.

Gregory develops a thesis on the carnivalesque in relation to Arkley’s diverse output – masks, grotesques, ornamented bodies, painted furniture – and ultimately brings the house paintings into this territory. Theatrical Facade, 1996, combines perspectival linework with Arkley’s freehand mastery of the airbrush in its curvaceous balustrades. The featurism attacked by Robin Boyd is celebrated here in paint. It is now also enjoyed by architects in Melbourne’s Suburban Detail of the Month competition and calendar project.

Arkley used irony in his treatment of the suburbs, but, like painter John Brack before him, refrained from satirizing his subject matter. As with the work of Edmond and Corrigan, Arkley dignified the place where most Australians live. Art offers architecture (and architects) a form of mutual engagement. Corbett Lyon is a collector of contemporary Australian art, including significant Arkleys in the exhibition (Shadow Factories, 1990, is one of several urban works), while Lyons is notable for its development of intensely patterned, large-scaled architectural surfaces such as at the VUT Online Training Centre, St Albans, and Swinburne University’s Lilydale campus, in suburban Melbourne.

Regarding the suburbs, Arkley once said, “What I would actually like to do is equivalent to when you’re driving along in the country and you look at the landscape and you say ‘Oh there’s a Fred Williams’. You change the way people see it. And you make people look at it.”3 It is not difficult to encounter his landscapes in the suburbs – more so, now, as they take on the glow of nostalgia. We might now look to art that engages with evolving contemporary forms of dwelling: McMansion-ville, the overseas student city apartment block, chronic itinerancy and the retirement resort. It’s out there.

1 Ashley Crawford and Ray Edgar, Spray: The Work of Howard Arkley, updated and revised edition (Craftsman House, 2001) provides much of this background.

2 Artists and Architects ’86, Transition no.17, June 1986. See especially Harriet Edquist, “Artist and Architect”.

3 Interview with Ashley Crawford and Ray Edgar, 1991, quoted in Spray: The Work of Howard Arkley.