An overview of Out from Under, showing the panels by Chris Bosse of PTW Architects.

Panels from left to right: Dale Jones-Evans Architecture; Terroir (in the corner); Tony Owen NDM; Andrew Burges Architects.

Detail of a model by John Wardle Architects.

Chenchow Little’s series of models. Image: Anthony Burke

Looking towards the work of John Wardle Architects on the back wall, with detail of m3architecture’s panel in the foreground.

The opening night of the exhibition. Image: Anthony Burke

Detail of the panel by Offshore Studio.

Detail of the panel by Staughton Architects.

Nicholas de Monchaux reflects on a San Francisco exhibition of young Australian practices escaping the mystic bush ethos.

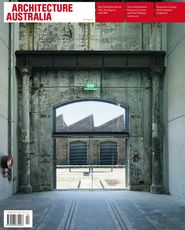

How does America see Australia – architecturally? In San Francisco, the exhibit Out from Under, viewed at the SFAIA, proposes a set of young Australian practices that, as characterized by curator Anthony Burke, together “signal a release from the grip of a mystic bush ethos”.

As much as they loom large in America’s image of Australia, it’s not Paul Hogan and Steve Irwin who preoccupy Burke, but rather the epic silhouette of Glenn Murcutt, whose bioclimatically vernacular Modern introduced most American architects to a compelling, distinctively Australian way of building decades ago. Admiration for Murcutt’s achievements has garnered him America’s and the world’s laurels – not just the Pritzker, but such bonbons as the Thomas Jefferson medal given in memory of America’s only architect-president.

After referencing the singular image of corrugated steel in the bush, however, Out from Under presents a blisteringly cosmopolitan set of architectural methodologies. As if to partially reassure a foreign audience, the galvanized sheeting is not completely H absent, but it’s hard to find, and where you see it – tubed and filigreed by Kerstin Thompson Architects of Melbourne, or buoyantly extruded by Tony Owen NDM of Sydney – it’s used in urban buildings as an ironic reference to a well-loved vernacular. And lest we make any mistake, the red triangles that cascade across Owen’s exhibit board resolve themselves below into a green-on-red X-ray of a violently stilettoed heel.

Paul Hogan, meet Kylie Minogue.

So what image does the exhibit as a whole present? From the desert coast of California, it is not a particularly coherent message, but a particularly relevant one. From urban galleries to private houses, from stadia to suburbia, Out from Under proposes a generation of Australian architects grappling with the same issues as their American peers, except possibly more so. The strands in American architectural practice that resonate most clearly with the San Francisco show are those describing the areas of contemporary practice – from low-tech ecological change to high-tech digital fabrication – in which the greatest uncertainties lie.

In some of the exhibit’s best offerings, low-tech and high-tech strands reinforce each other to open new architectural territory. In Dale Jones-Evans’ Art Wall for King’s Cross in Sydney, for example, a massive Coreten wall becomes a laser-etched, filigreed sunscreen whose decorative surface defies conventional architectural categories. More subtly, the Water Cube invented for Beijing’s 2008 games by PTW Architects with Arup and CSCEC (represented in the exhibition by Chris Bosse and his works) seems the essence of an unbuildable digital rendering – until the glorious construction photos reveal that the pores of the delicate structure are, in fact, giant and very real plastic bags. Projects by m3architecture of Queensland and Minifi e Nixon of Melbourne appear to render the traditional masonry of Australian urban construction into delirious surfaces of colour and texture whose life cycle would definitely seem to have included a span as computer bits.

In 1980, around the same time that Glenn Murcutt’s name first appeared in American architectural journals, one of America’s own giants, critic Gore Vidal, famously quipped, “Sydney is everything San Francisco thinks it is – and far more beautiful.” And true to form, many of the featured projects resemble, and sometimes outshine, their American counterparts. Yet the most eye-popping projects in Out from Under present a picture of Australian practice that is, wonderfully, less beautiful than its American big brother. From McBride Charles Ryan’s stripy facades (as in the Templestowe Park Primary School Multi-Purpose Hall) to Minifie Nixon’s giant aluminium pores (the VCA Centre for Ideas), the uncompromising forms and colours of many of Out from Under’s urban buildings, one has to admit, would have a hard time getting built as permanent structures in America’s downtowns. With their festival appearance, such buildings seem to recall the temporary nature of all building, not least in the improbable built ecology that Australia shares with this other Pacific coast.

It is on this note that the lessons of Out from Under are perhaps the most provocative. For all the exhibit’s efforts to declare itself an urbane alternative to the bush architecture by which Australian practice might be stereotyped, it is useful to recall that Australia’s cities are as ecologically vulnerable as its romantic countryside, if not more so (as San Francisco worries about a second year of drought, Sydney enters its second decade of the same). The ecological connections to the West Coast are especially clear in the timeline of Sean Godsell’s work presented by his exhibit boards, which departs Australia for new commissions in the Arizona desert.

Finally, a sense of ecological transience is reinforced by an image in the exhibit that treasures not a building, but rather its gradual disappearance.

Neeson Murcutt presents a project for a brick lookout in Sydney’s Olympic Park. At the centre of the site, the masonry blocks are responsibly ordered, yet at the project’s periphery, we face a pile of decomposing blocks (the project’s most beautiful image), whose edge is continuously eaten, and so re-engineered, by the swirling waves of Sydney’s great harbour.

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Jul 2007

Words:

Nicholas de Monchaux

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2007