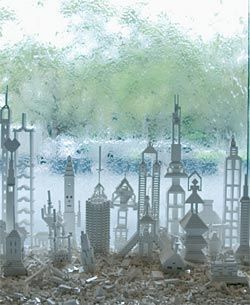

Olafur Eliasson’s The Cubic Structural Evolution Project 2004, National Gallery of Victoria. Purchased by the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation Grant 2005. Detail seen through the NGV’s water wall.

Looking out through the window.

Members of the public were invited to construct the project from white plastic Lego blocks.

Detail.

Under construction.

Mounds of white blocks form a layer of debris around the tower bases.

Detail.

The project grew larger and more complex over time, as more people added their contribution.

Karen Burns considers The Cubic Structural Evolution Project 2004 by Olafur Eliasson.

If you haven’t yet heard the Icelandic/Danish artist Olafur Eliasson spoken of in architectural circles, you probably will soon. A star of contemporary installation art, Eliasson appears with increasing frequency in architectural writings, studio projects and conversations. An interview with the eminent New-York-based architectural theorist Mark Wigley was included in a 2006 book on the artist, Your Engagement has Consequences On the Relativity of Your Reality, and a recent architectural essay collection, Soft Architecture, includes Eliasson’s famous Weather Project, a large-scale installation at the Tate. The artist’s work parallels a number of contemporary architectural interests while remaining publicly critical of architecture’s institutional power and residual Modernist impulses.

It is a little disappointing, therefore, to be somewhat underwhelmed by one of Eliasson’s works, The Cubic Structural Evolution Project 2004, exhibited at the National Gallery of Victoria earlier this year. “It’s pretty,” said one of my students.

Eliasson describes his installations as constructions, seeking to avoid the word “architecture” by favouring the making of environments. We might counter this hard-edged polemic by noting that increasingly, architecture is investigating the ways in which a building can successfully manage its internal microclimate through a greater regard for external conditions, in the pursuit of more environmentally sensitive design. Moreover, architecture is also concerned with tactile sensations and affect. Helene Furjan, in one of the Soft Architecture essays, argues that the new architectural skin is a “thick skin”, attentive to its adjacent ambient conditions. Eliasson’s wary distance from architecture is perhaps rooted in a reaction to Modernism, but his political critique of capitalism and sense that art should be distant from this economic system may also provide a clue to his stance.

His materials are ephemeral. This is post-object art. His projects are usually participatory, and in this he eschews the role of the solitary artist as the arbiter of a work’s production and meaning. Many of these concerns are shared by architects, so I find his anti-architecture position a little puzzling and a little misguided. It feels as if he is wrestling with the ghost of what architecture has been. Perhaps it’s best to ignore this and look at productive intersections with contemporary architecture.

The Cubic Structural Evolution Project 2004 enshrines Eliasson’s fascination for and critical disagreements with Modernism. In seeking to fashion a post-Modernist sense of space, Eliasson, I assume ironically in this project, uses some fundamental elements of twentieth-century space. This work reflects on the continuous production of urban space and the fluctuating demolition and rebuilding of cities. His chosen materials are quite spare and simple: some four hundred thousand white Lego blocks deposited on a long white timber table about eight metres long and two metres deep, accompanied by white stools for the participants, and a mirrored tabletop that covers most of the surface of the table. Using the Lego blocks, gallery-goers were invited to construct the project.

On the two occasions I visited the installation, building was well underway and many towers covered the table. The towers varied in their form, from traditional Modernist slabs to skeletal open frames, Metabolist towers, crane-topped roofs and a massive, leaning, solid wall tower. And my personal favourite, a robot tower. Despite the variety, the work was aesthetically unified because of initial decisions made by the artist. And these decisions were central to the aesthetic sensibilities governing the project and the determining conditions framing the trajectory and choices of the participants.

Colour choice was carefully controlled: only white Lego, of one dimension, was available. How different, messy and more like a city the project would have been if all the colours and sizes of Lego had been made available.

Aesthetic control over colour was further exercised in the choice of a white painted timber surface for the table and stools. Undoubtedly the decision was ideological as well as aesthetic. Eliasson, in an interview with Wigley, associated Modernist architecture with whiteness. During the interview, conducted after The Cubic Structural Evolution Project 2004’s production, Wigley observed that the colour white only became a hallmark of Modernism in the postwar period. Earlier, canonical Modernism had used beige and other counterpoint colours.

Perhaps Eliasson knew that Moshe Safdie had used white Lego blocks in the design process for Habitat.

Nevertheless, this one aesthetic choice provided a means of artistic control in a project generated by its users. Other directions may have been set for participants. Is it possible for people not to build towers when the curatorial wall text describes this as a city project? The choice of material may have guided participants further. Lego is designed for vertical stacking rather than horizontal extension. People are generating this project but they are operating within a set of constraints determined by the artist.

The miniaturized white city of towers was visually alluring, in part because a model of a city allows us an encompassing view of a space that in its lived reality exceeds our powers to grasp it. These are the pleasures of Modernism as well as some of its perils. But a neat, totalizing vision of the well-made and orderly city was refused in this project. I was most compelled by the hundreds of white Lego blocks that piled up around the bottom of the towers and formed rising white mounds.

Many of the towers were obscured at ground level, mired in this white debris. Ruination from below threatened.

These discarded or as yet unused Lego blocks resonated with metaphorical possibilities in a way that the towers’ literal forms did not. The mounds could be snowdrifts or ruins or remnants of the past, |or war-damaged, collapsed structures. And in the tension between the two kinds of construction a larger vision of history emerged, wider than Modernism’s shores. Eliasson is undoubtedly part of this history, working upon Modernism’s ruins.

The installation was simple and visually appealing, unified in its white aesthetic and presenting a compressed history of twentieth-century towers. The tower prevailed, suggesting the extent to which these forms have permeated a larger public consciousness. But those of us internal to architecture are well acquainted with the critique of Modernism, and Eliasson’s other projects offer different kinds of spatial experience.

The Weather Project – a large, ephemeral installation of yellow light and fog – was experiential, ambient and an affect-charged engagement with the viewer’s senses. The Tunnel used non-conventional building materials to construct a wire-arched tunnel whose external “wall” comprised rows and rows of terracotta pots housing flowering pelargoniums. (At least, that’s what these botanical specimens look like to this non-horticulturalist.)

My disappointment, then, on viewing the work at the National Gallery was founded in a passing acquaintance with the artist’s other works, which, in their use of non-traditional materials, sensation and climatic ambience, seemed to intersect with the direction of architecture’s contemporary currents.

The Cubic Structural Evolution Project 2004 was pretty, but not as memorable, nor as promising of alternative environments, as some of the artist’s other works.

Karen Burns is an architectural historian, theorist and critic based in Melbourne.