THE FLEETING IMAGE

San Silvestro, Bevagna, Italy (Maestro Binello, 1195).

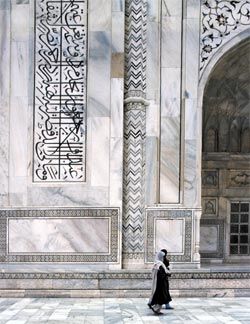

Taj Mahal, Agra, India (1630–53).

Mezquita, Cordoba, Spain (875–987).

Fish-eye view of the dome of St Peter’s Basilica, Rome, Italy (Michelangelo, 1593).

Philip Goldswain reviews an exhibition of architectural photographs by Michal Lewi.

The seventy-seven photographs recently exhibited at the University of Western Australia’s Cullity Gallery gave a small glimpse into the impressive archive of selfdescribed “serious amateur photographer” Michal Lewi. Taken over 35 years of travel, the images document the retired Western Australian lawyer’s knowledgeable interest in architecture. Born in Prague, Lewi was educated in England and practised law in Singapore before settling in Perth in 1961.

As chairman of the National Trust of Western Australia he photographed many of the buildings under its custodianship and his images are one of the best records of what has now disappeared under the wrecker’s ball. However, instead of the pragmatic and the prosaic concerns of those documentary photographs, these images are concerned with the emblematic and the poetic. With a remarkably consistent eye, careful and deliberate composition and painstaking timing they reveal a perceptive and lyrical understanding of architectural space and its occupation.

Lewi adopts, for the most part, the classical three-quarter view, allowing the viewer to comprehend the building’s form in a single image. Other compositions reveal further subtleties – in some images Lewi gazes upward to the vaulted ceilings of Gothic cathedrals, revealing the variety of relationships between the ribbed ceilings and the walls they spring from.

Lewi also takes advantage of the felicitous moment. A wizened Italian man stoops to check his watch, his bent form echoing the twisting columns on the church of San Silvestro behind him. Two veiled Indian women walk past the Shan Jahan’s “monument to love” where someone has scrawled a love heart punctured by an arrow onto the white Persian marble. Three weary nuns, bent over with the burden of their religious calling, emerge from the heavy stonework of their abbey’s church.

Four men at prayer in Old Delhi’s Jami Masjid look like they are consulting the 70s timepieces inlaid into the red sandstone, rather than Mecca.

In contrast to the specificity of these moments many other photographs appear to exist outside time through composition and manipulation. A carefully framed view of the Ibn Tulun Mosque in Cairo artificially suggests a skyline unchanged since the Middle Ages. An elevation of George Temple Poole’s gold-rush era Land Titles Office in Perth is actually a view that was never seen, made possible here through the digital removal of a Modernist building from the background – a premonition of the offending building’s eventual demolition.

Under the curatorial direction of Bill Taylor and Hannah Lewi, these disparate and wide ranging photographs were organized into subtle groups that rewarded repeated viewing. Similar photographic compositions collected divergent images such as San Miniato al Monte, Florence and Palladio’s Villa Poiana or Fischer von Erlach’s Karlskirche and the Kizhy Cathedral, Russia. An interest in reflectivity placed the Barcelona Pavilion next to a moated temple in Beijing’s Forbidden City and the Alhambra in Granada. A similarity of architectonic elements organized images from across the Mediterranean, linking Sicily, Bologna and Egypt. Contrasting responses to similar religious spaces were also hung together: the exquisitely ordered and densely columned space of the Mezquita in Cordoba and the empty forecourt of Jami Masjid hinted at the different manifestations of sacred space in Islam.

This organizational technique meant that images of the same building were scattered through the gallery, allowing the viewer to draw together these careful groupings into a cohesive whole. For instance, the same red and white stone arches of mosques can be seen in buildings from Spain, Turkey and India. Different aspects of the Taj Mahal are revealed through its various placements throughout the exhibition space as well as creating connections between it and other buildings that would otherwise remain isolated from one another.

Some of the most evocative images are those where the human figure is central to the image. A single worshipper prostrates himself in the carpeted expanse of the Suleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul.

A Mao-suited man gives scale to a red lacquered Chinese doorway. A whitewashed wall in Jaisalmer painted with images of Hindu deities becomes the backdrop to a herd of holy cows being fed by a turbaned passer-by. Rather than merely being a device for adding scale, these figures reinforce the fleeting nature of the photographic instant.

These coincidental juxtapositions lend a specificity to the image that the figureless photographs lack.

Lewi’s images also point to the displacement by the camera of the sketch book on the modern architectural Grand Tour. The scrutiny of the mechanical gaze, rather then the act of drawing, is the new mode of revelation. Unlike the process of drawing, where understanding is gained through the observant eye and the coordinated hand, the revelatory moment of photography is in its later examination.

However, the notion of capturing the very specific light of a specific place in a mechanized and industrialized process has modern poetic resonance that might challenge the romance of the sketch. The architectural camera can have diverse purposes – a medium of record, a device of self-education as well as an apparatus of possession.

The scrutiny of the architectural image is particularly appropriate when speaking of the photographs of travellers from the Antipodes. Simon Anderson has traced the relationship between photographs and the “flat and thin Australian aesthetic” of the architecture of Modernist Gordon Finn.

Gus Ferguson has published and exhibited images from his “architectural pilgrimages” of the 1960s, which concentrated on the vernacular architecture of the Mediterranean and the Middle East and which deserve further critical attention. Harry Seidler’s recent publication, The Grand Tour (2004), reads like a photographic sketch book.

To this we can now add the images of Michal Lewi who, in his generous donation of these images to the school of architecture at UWA, has provided another opportunity for the close investigation of the intricate relationships established by the photographing of buildings.

PHILIP GOLDSWAIN IS A LECTURER IN ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA.