74’ 56 [SPACE IN THE SOUND OF ARCHITECTURE]

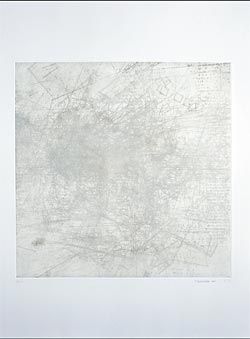

PHOTOGRAPHY ROBERT COLVIN. Overview of the recent exhibition by Chelle Macnaughtan. Three lines of prints hung in the gallery space, while the plates used to make the prints lined one gallery wall.

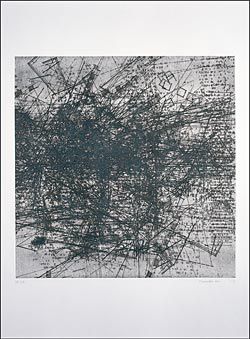

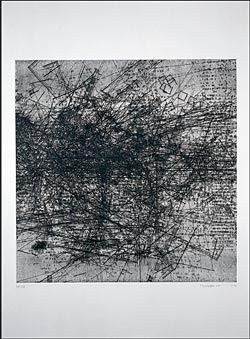

One of the series of prints hung across the exhibition space. Pulled off the same plate and inked in a single batch, the prints become darker over the series.

Alex Selenitsch reviews a recent exhibition by Chelle Macnaughtan, which uses printmaking techniques to explore links between sound and architecture.

“Art is without noise (as that term is employed in information theory): art is a system which is pure, no unit goes wasted…” Roland Barthes Image Music Text.Barthes’ contemporary version of the Renaissance idea of wholeness – where nothing can be taken away or added – emphasizes the artwork as a product, as an object, despite the use of the word “system”. Against this, architecture and music (and theatre too) share a large zone called production. In this zone, architect and composer are parallel figures with similar tasks.

The key document in this common zone is the score. All artists must imagine something before it exists, but in normal practice architects and composers have to put it in writing for others to realize. This “writing” concerns both intention and fact – both are couched in codes like plans, sections and elevations, or five lines with dots and symbols on them.

This is where Barthes’ proposition comes unstuck. No score can fully describe the facts, let alone the intent, of a creative idea.

Interpretation, addition and excision are realities of performance. In Testaments Betrayed, Milan Kundera writes a deeply felt examination of the things done by others to the music of composers, regardless of the explicit instructions of the composer.

Similarly, all architects know the strange feeling that swells up, 200 metres or so from the site, before they inspect the difference between the score and its performance.

Composers tackled these issues head-on in the 1950s and 1960s. One of their aims was to separate essential instructions, to be precisely followed, from those that could be observed in an arbitrary fashion (if at all).

The unique occasion that is every performance switched into compositions that could be different each time they were performed, or different when they were assembled into a score. Chance or hazard – the unpredictable – became an aesthetic issue. As well as the liberating effects on performers and audiences, and a subsequent shuffling of the traditional power relations between composers, performers and listeners, the 1950s and 60s produced lots of visually appealing scores. Composers invented remarkably individual graphic solutions to the problems of notating the production of sound. The magic of making marks infused the research and shifted music’s visuality into the same zone that architecture, drawing, painting and design occupy.

This is the zone explored by Chelle Macnaughtan in a multiple work recently installed at Melbourne’s Über gallery. Über is a deep, shop-like space, with white walls (of course). Nine printing plates, each 500 millimetres square, were fixed in line to the long wall on the left-hand side of the entrance. Twenty-seven prints were then hung in the deep space, in three lines of nine each, as if to dry. Over this played an ambient soundtrack of Macnaughtan walking through the Jewish Museum in Berlin. On my visit it was particularly quiet (“Probably the bit in the Holocaust section,” said the artist when I asked about the lack of sound during my visit). The first line of prints on the left was white, the middle one grey, the right-hand side one black. The move from white to black was steady and consistent, all the prints having been inked from a single batch made darker and darker over the series. White, grey and black sets were made off the same set of nine plates creating three sets of prints, from white to black, going through the whole sequence.

In the sequence, the biggest shock was the jump from the first print, which was embossed paper – a pure signal – to the next print, which was the first to carry the noise of the ink. Through the sequence the ink got noisier and noisier, allowing the pure system (to use Barthes’ term) to be seen.

This system was an overlaid field of lines and numbers. The graphic image was derived from two-dimensional representations of the artist’s recording of all sounds while walking through the Jewish Museum, a combination of a specific path and constantly total sound envelope.

This effect was easily seen in the prints: they were all different, but all the same.

“All different but all the same” is a result of their process of composition. This is a method that selects pre-existing systems to survey, extracts subsets of patterns, then overlays these subsets to create new patterns. Its vernacular or non-art talisman is the map; its aesthetic principle is the moiré or interference pattern. Images are invariably over-determined; they have too much data, which resolves into images of crowds, flocks, clouds, galaxies and so on.

Daniel Libeskind has a ghost-like presence in this exhibition. He is there in Macnaughtan’s choice of sound source, in her use of a quote and in the citation of Libeskind’s Chamber Works in her artist’s statement. But Libeskind is only the noisiest of the architects who use this process. Many other artists are also working in this way across many categories and styles, and Macnaughtan’s work could equally be thought of as a walk through this kind of compositional process.

The importance of the method in 74’ 56” is that it can apply both to architecture and to music, and that the outcomes are not illustrations or translations, even when specific artworks are used as the system of the initial survey. This makes Macnaughtan’s installation pleasingly difficult to classify. The prints could be maps, images of sound (both as record and as prediction), or images of dense space.

More importantly, these works are prints, peeled off the nine plates lined up on the wall of the gallery. The plates are the scores of the work, and each print is itself a performance, even a ritual, as anyone who has been engaged with printmaking can attest. Macnaughtan’s use of printmaking provides a mediating arena between architecture and music. The movement from the survey to plate to print – from score to performance to record of the performance – is a model for a new process that links a score to making to architecture.

This sounds conventional, except that in Macnaughtan’s model of the sequence, as offered through this exhibition, the score and making are directly and physically connected. The same person, the architect/composer, makes the plate and makes the print: imagine such a situation for architecture. ALEX SELENITSCH IS A MELBOURNE-BASED POET AND ARCHITECT, AND A SENIOR LECTURER IN THE FACULTY OF ARCHITECTURE, BUILDING AND PLANNING, UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE. CHELLE MACNAUGHTAN IS A PHD CANDIDATE AT RMIT UNIVERSITY. SHE RECENTLY RECEIVED THE INAUGURAL RAIA LYSAGHT SCHOLARSHIP, WHICH WILL HELP FUND RESEARCH EXTENDING THE IDEAS EXPLORED IN THIS EXHIBITION.