Entry to Supermodels . Image: Brett Boardman

World Tower Comparison, by Richard Braddish, Urban Design and Heritage, Planning Department, City of Sydney. The series of models was located along a window edge of the exhibition space. Image: Brett Boardman

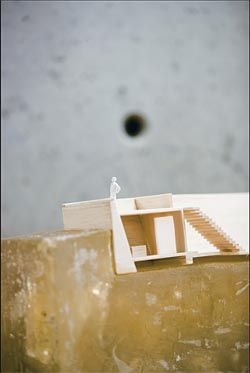

Detail of Mt Stromlo Walkway by Amelia Holliday. Image: Brett Boardman

Detail of some of the East Darling Harbour competition models. Image: Brett Boardman

Detail of Wall Panel by Simon Grimes, with Negative Space by Jenny Hien and Form Generation by Gaurav Malhotra seen in the background. Image: Brett Boardman

Overview of the exhibition with Timber Framing by Virginia Wong See in the foreground. Image: Brett Boardman

Marian Macken considers Supermodels: an exhibition of space and form in architectural models – a ‘tablescape’ of diverse architectural models curated by Sam Marshall.

In the Soane Museum, in London, hangs a painting which shows all the architect John Soane’s works, both built and unbuilt, as models of different sizes and materials, packed into a single huge room. Robert Harbison has written that this brings out the “miracle of models, which can put the whole world in a small space”. The exhibition Supermodels – curated by Sam Marshall, with financial assistance from the NSW Architects Registration Board’s Byera Hadley Travelling Scholarship – takes a similar approach, in displaying nearly 450 models made, predominantly, by Sydney architects and architecture students.

The exhibition is in three spaces. The first contains models made as part of submissions for the recent East Darling Harbour competition, and, along a window edge, a personal overview of local and international buildings and their relationship to the world’s tallest building badge, by Richard Braddish, City of Sydney Council model maker. In the other two rooms, Marshall has gathered together models from the offices of practitioners.

According to Marshall, the impetus of the exhibition was to create a medium between architects and the public, via the showing of architects’ wares, to form a “table-scape” of models at chest height and eye level.

The models range in type, including modelled vignettes of the development of individual schemes; presentation models; interior models; toy construction kits; detail construction models; sectional urban studies; models made after the fact, paring back built complexity to post factum conceptual simplicity; modelled interpretations of well-known buildings; and models not actually proposing a built work, but exploring an abstract spatiality.

The models range in scale, from those displaying an obvious 1:100-ness to those needing a title to clarify interpretation.

For example, SJB Architects’ white card and plastic model, titled Facade Study, could just as believably have read “Joinery Unit Study”. The catalogue allows this freedom by omitting scale information. The models are made of different materials, from monolithic lead (Quarry, Dale Jones-Evans Architecture) and plaster (House for a Billionaire, Wes Grunsell) and the mono-materiality of balsa (Backpacker Hostel, Connie Zhang) and boxboard (Negative Space, Jenny Hien) to assemblages in wood, metal, resin, plastic, clay, sandstone, bronze and folded paper.

The East Darling Harbour models, due to their sharing of site and brief and scale, invite initial comparisons of content and scheme. But these models, seen within the greater context of this particular exhibition, and cut off from the symbiosis of their drawings, invite examination based on other criteria. They are seen here within the realm of model making itself, and it is the representation of the city, the portrayal of the existing, that invites observation.

Interestingly, this forms a connection with the rest of the exhibition: it is the site of the making of those other models.

The act of model making, of making miniature a proposed building, creates fascination. Qualities associated with this change of scale include intimacy and interiority. However, as Susan Stewart has written, the act of holding the miniature within the hands creates qualities of the giant in the viewer, leading to exclusion and distance. Architects have acknowledged this remoteness by creating models that have taken on the role of presenting architecture, not representing it; the model as referent, with its own identity and presence and, therefore, perhaps self-consciousness. As Michael Graves has said, “We’re not making real buildings; we’re making models of ideas.”

The origins of this shift within model making lie in the 1976 seminal exhibition Idea as model, curated by Peter Eisenman, in New York. Eisenman intended to display the model as a conceptual rather than a narrative tool, revealing the artistic existence that models could have, independent of the project they represented.

However, Christian Hubert, in his essay in the catalogue of this exhibition, writes of the extent of this objecthood: “The space of the model lies on the border between representation and actuality … neither pure representation nor transcendent object.

It claims a certain autonomous objecthood, yet this condition is always incomplete.

The model is always a model of. The desire of the model is to act as a simulacrum of another object, as a surrogate which allows for imaginative occupation.”

The models in this exhibition are the manifestation of the act of making. There is a relationship between the model maker and the model, and between the viewer and the model. Therefore, the mark of the hand of the maker transfers to the viewer, something a photograph of the built work can never do. In Supermodels , sometimes the eye is drawn to the coarser models, the ones with uneven edges pinned together, such as Sam Crawford Architects’ Bathroom Addition or the model by Bruce Eeles, made when he himself was a student. There is an honesty and immediacy to these types of models, exposing the craft of the profession, revealing a healthy shedding of the usual editing of an office’s output before it reaches the public gaze. This lack of pretension is contributed to by the location of the exhibition itself – not in a white-walled gallery, but, instead, in an as-yet-unleased commercial space, with bare concrete block walls and fluorescent lights, the models sitting on raw plywood. Unfortunately, some sit within their own acrylic cases and, due to this, are slightly removed from the viewer and their modelled neighbours.

Often group shows fail due to their generality. However, in this case, because seemingly dissimilar architectures are placed next to each other, connections and similarities can be speculated on that would not exist at a built scale, or across pages of drawings. By providing a core sample of three-dimensional representation, via a driftnet approach of gathering, the exhibition presents an overview of one city’s architectural labours. Supermodels provokes consideration of other exhibitions, such as a similar survey of the spatial representations of allied professions – landscape architecture’s rendering of terrain or stage design’s theatre sets.

Models are usually seen as exploratory and preparatory to a building. The emphasis is on their generative qualities, and their revelatory capacities in getting to the design. The models in this exhibition are no longer “current” within their own design processes, and hence are separated from their earlier roles. They have become records of a process, inviting reflection that a space of time offers. The usual way of documenting architecture is by photographing the built work, which often involves the ubiquitous stylist’s fitout.

In the case of Supermodels, architecture is documented by dwelling on the artefacts of architecture’s process, allowing them to elucidate, narrate and comment. And as the exhibition disregards architectural classifications at a built level, it leads to an inclusivity sometimes missing from the profession.

Marian Macken is a master of architecture (thesis) student at the University of Technology, Sydney, writing on the topic of models. She was also an exhibitor in Supermodels. Supermodels showed at the St Margaret’s complex, Sydney, in September.