Beautiful and powerful, the works in Ian Friend’s recent exhibition respond to romantic ideals of archtiecture and the work of Giuseppe Terragni.

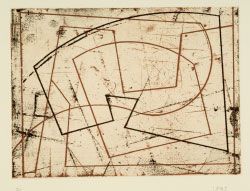

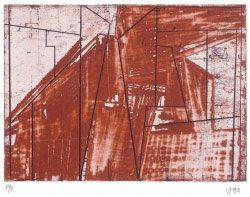

Soft-ground etchings (1995). A collaboration between Friend and Melbourne printmaker John Loane, the works record every detail of the printing process. Terragni V.

Terragni I.

Terragni III. Photographs by Gary Sommerfeld.

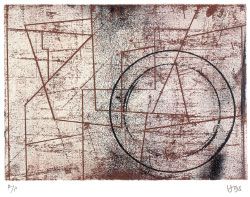

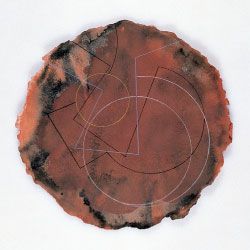

Tondo: Terragni . The paintings are the outcome of slow processes of accretion, which emphasize their materiality.

Futures Technology Centre, Hobart, 1995, a collaboration between Friend and artists Kevin Todd and Sara Lindsay and architect Paul Lan. Enlargement of the business card for the concrete company and client for the project, Duggans.

The build and unbuilt architecture produced during the brief career of the Italian Rationalist Giuseppe Terragni (1904–1943) has inspired not only architects and historians but also artists in other disciplines, including Ian Friend. A British-born artist, trained in drawing and painting, a graduate of the Slade School of Fine Art in London, Friend immigrated to Australia in 1985 and since 1996 has resided mostly in Brisbane. As one of his architect friends, I know he is an avid reader of poetry and architecture, infatuated by both. But most practising architects would not identify with Friend’s definition of architecture. It is a romantic, utopian one – practised nowadays only by vanguard architects but still a lingering dream of many – and is perhaps best summed up by a statement Friend delights in, “Architecture should be left to artists and structural engineers!” It is no surprise, then, that he has been preoccupied by the architecture of Terragni and has responded to it in a series of works displayed in his exhibition, Ian Friend: Terragni , at the Queensland University of Technology Art Museum.

The exhibition collates works Friend produced in the mid-1990s, in response primarily to Giuseppe Terragni and Pietro Lingeri’s unrealized Danteum in Rome (1938). Friend became acquainted with this through Thomas L. Schumacher’s 1993 book, The Danteum: Architecture, Poetics, and Politics under Italian Fascism , and his 1991 book, Surface & Symbol: Giuseppe Terragni and the Architecture of Italian Rationalism . The Danteum was to be a centre and museum to celebrate the writings of the thirteenth-century poet Dante Alighieri, a primary source of Mussolini’s political aspirations for Italy. Terragni and Lingeri’s design emerged directly from Dante’s poetic spaces of Paradiso, Purgatorio and Inferno as outlined in his The Divine Comedy . The original metaphysical watercolours of the project preface Schumacher’s 1993 book. For Friend, one of the most inspirational and seductive was the watercolour of Paradiso, an ethereal room filled with a matrix of glass columns. Another tangential influence was Paul Virilio’s Bunker Archeology , published in English in 1994, in particular the chapter “An Aesthetics of Disappearance”. As Friend wrote in Transition 61/62, “all of [Virilio’s] photographs of Nazi bunkers sinking into the sand [are] extraordinarily beautiful” and “I believe his thesis is entirely accurate in that fascism can only survive by the dynamic of constant expansion and that to define defensive borders (through concrete bunkers) signals the death of that dynamic and the political demise of fascism.”

The prints and related drawings on display at the QUT Art Museum are equally “extraordinarily beautiful”. They include two Indian ink, gouache, watercolour and crayon on paper Tondo: Terragni works; five soft-ground etchings titled Terragni and twenty-five working proofs; photographs of the Futures Technology Centre in North Hobart – a public art project commissioned by the Tasmanian Government, which Friend collaborated on with artists Kevin Todd and Sara Lindsay and architect Paul Lan; the constructivist-style 1800 x 1600 mm lino print and crayon Report from the Besieged City no. 1 ; and the Indian ink, gouache and pencil Lictor’s Tower no. 1 and Lictor’s Tower no. 2.

Friend’s initial response to Terragni and Lingeri’s Danteum and the life and death of Fascism was manifested in a series of twenty-five tondi , of which only Tondo: Terragni Set 6, no. 2 and no. 3 are on display. The two 300-mm-diameter circular paintings are the outcome of Friend’s slow process of layering washes of ink, gouache and crayon over on Twinrocker handmade paper, in what he has described as “a kind of accretion”. The process is both constructive and destructive – the works are built up by a technique of addition and subtraction and the materiality is emphasized by the exaggerated feather deckle, which is itself emphasized rather than concealed by the manner in which the works are framed. Perhaps as a consequence of this sequential, staged method, the tondi ingeniously capture the ethereal quality of the Danteum watercolours through abstraction without any hint of mimicry. Their melancholic beauty somehow returns also to Virilio’s bunker architecture.

The other significant framed series in the exhibition is a set of five soft-ground etchings titled Terragni , which the QUT Art Museum acquired in 1998 for their permanent collection. They are the outcome of Friend’s collaboration with Melbourne printmaker John Loane of Viridian Press. The delicate production technique of soft-ground etching records fine lines, smudges and fingerprints of the artist – every detail of the printing process – in a two-plate combination using Black and Burnt Sienna. The exhibition also contains remnants of the printing process used to create these five works, which curator Gordon Craig argues “give an insight into Friend’s creative process”. These remnants include twenty-five unframed working proofs which float loosely on one wall, pinned only in the top corners, and the ten highly polished copper printing plates displayed in a central cabinet.

The photographs of the Futures Technology Centre affirm Friend’s philosophy that architecture is an artistic practice and make a sharp return to the architecture of Terragni. Friend wrote to me of it, “the building was the first (and only) example in Tasmania of artists (myself, Todd and Lindsay) working with an architect (Lan) to make art part of the building, rather than an obligatory afterthought … i.e. the art is in the building, not decorating it, or acting as an adjunct, or architectural conceit.” The facade and plan of the Futures Technology Centre test geometry in the same ways Friend’s tondi and etchings do. As a consequence, the Hobart building contains essences of not only the Danteum but also the geometrical explorations in Terragni’s seminal Casa del Fascio, Como (1932–36). As a critique of entry and the maintenance of boundaries, a feature of the Danteum, an outsider is forced to enter the Futures Technology Centre from the side rather than the front.

The remaining three works in the exhibition, the large Report from the Besieged City no. 1 and two small paintings of Lictor’s towers, seem less directly influenced by any particular building. More personal experiments with the architectural concepts of political enclosure and territorial defence found in the Danteum, Virilio’s photographs and the politics of Fascism, they also draw on a poem about invasion and architecture’s relationship to it by Zbigniew Herbert, the Polish poet and fighter in the underground resistance against the Nazis. The work’s title is taken from the name of this poem, in which Friend has highlighted the following words:

“I am supposed to be exact but I don’t know when the invasion began two hundred years ago in December in September, perhaps yesterday at dawn everyone here suffers from a loss of the sense of time all we have left is the place the attachment to the place we still rule over the ruins of temples spectres of gardens and houses if we lose the ruins nothing will be left”

Accompanying the exhibition is a catalogue of poetry called Architecture’s Tomb by Robert Nelson, art critic for The Age . Written in response to Friend’s Terragni works, Nelson’s poems bring together the media of poetry, architecture and painting within which Friend operates. It also cleverly makes comment on Terragni and Lingeri’s Danteum legacy. I conclude with Nelson’s words:

“If Terragni’s ideas had achieved credibility, no one would challenge the builder’s nobility, neither as a modernist nor as a man whose design is a base and invidious plan. As a failure, however, it acts as a tomb which remains every architect’s ultimate room.”

Igea Troiani is a modern architectural historian and partner in Happeninc. Ian Friend is a co-founder with Robyn Daw of Art Bunker.