ONE OF BRISBANE’S OLDEST PRACTICES HAS HAD A REMARKABLE EFFECT ON THAT CITY’S FABRIC. DOUGLAS NEALE REVIEWS AN EXHIBITION AND FILM BY IGEA TROIANI WHICH CELEBRATES THE WORK, THE PEOPLE AND THE PRACTICE.

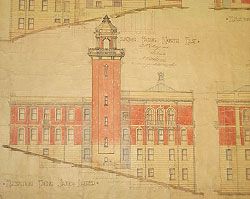

Detail from the original drawing of the Trades and Labour Hall (1919) by Charles McLay. Fryer Library University of Queensland.

Overview of the exhibition. Photograph Scott Burrows.

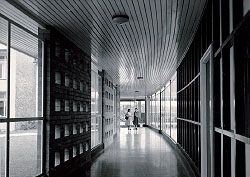

Interior of the curved walkway at Women’s College, University of Queensland.Women’s College Archive.

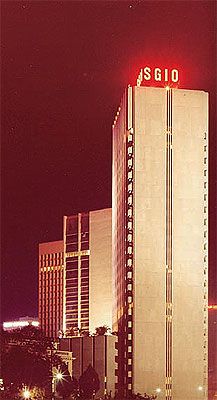

SGIO Tower, by Keith Frost (1971). Conrad Gargett Architecture Archive

IN THE LATE 1960s and early 1970s Brisbane began to transform its identity, particularly in the CBD. Today, one of the city’s more memorable and defining urban experiences is to be had travelling north along the Southeast Freeway, swinging onto the Riverside Expressway and then into the space of the CBD. This experience is generated, in no small part, by a tapestry of tall buildings (all less than thirty years old) held tightly by the bend of the river as it picks its way through the complex array of hills and ridges that figure the Brisbane landscape.

It’s this tapestry that Professor Michael Keniger refers to when describing the work of Conrad Gargett Architecture (or, more familiarly, Conrad and Gargett) in the introduction of the film that accompanies a modest though elegant exhibition celebrating the firm’s 115 years of practice. Curated by Igea Troiani, who also produced the film, the exhibition showed at the QUT Art Museum.

As Keniger observes, Conrad and Gargett’s work resonates within Brisbane to a remarkable degree. During the mid to late 1980s the office had a very large working model of the city. Students were charged with keeping it up to date. When I arrived in 1988 as a final year student I was curious to know why more than half the towers were blue card and the remainder white – of course, Conrad and Gargett were responsible for the blue! Two things struck me as significant at that time and have remained with me. Firstly, I was staggered to discover Eddie Hayes (of Hayes and Scott) tucked away at the back of the office on floor 21 of the Suncorp Building (formerly SGIO). Even as a student I regarded Eddie as a major local hero, and here he was at Conrad and Gargett, easing into retirement doing contract documentation. The other significant thing was the building itself.

The 24-storey SGIO Building, completed in 1971, was one of the city’s first ventures in reshaping its identity. Designed by Keith Frost, who sadly died while still a director of Conrad and Gargett, SGIO is emblematic of a group of buildings that transformed the practice. It is also one of the most successful and innovative towers in the city. Through a combination of passive climatic design and imaginative core arrangement, it offers two-way unimpeded views through the depth of the building, a rare phenomenon in tower design. In addition, the public forecourt fountain and landscaping, roof-level restaurant, car parks and theatre contained within the building programme brought an unheralded urban sophistication to Brisbane’s architecture.

The SGIO Building also demonstrates two aspects of the practice which have endured over the last 115 years: the capacity to attract skilled and noted architects to a corporate framework, and a regard for applying, quietly, sound design principles that embellish the life of their clients. Frost, in his role at C&G (as it was known from the 1970s to the 1990s), was a Brisbane equivalent of Skidmore Owings and Merrill’s Gordon Bunshaft at the height of that US practice’s great experiment with the high-rise tower fifteen or twenty years earlier. Following Frost, Sipen Rojnavibul has assumed a similar role. Her work for the Commonwealth Bank and the State Law Building (affectionately regarded by the citizenry as “Gotham City”) continues this mode. Many other notable architects came within the orbit of Conrad and Gargett. The clever graphic on the cover of the exhibition pamphlet lists all the individuals who have worked at Conrad and Gargett over the practice’s life. Apart from Eddie Hayes, eagle eyes can spot Paula Whitman (current President of the RAIA Queensland Chapter), Rex Addison, Brian Donovan, Graham Bligh and many others.

The exhibition is a reminder of the breadth and depth of the practice’s work. The portfolio runs to thousands of projects across the full gamut of building types, including hospitals, schools, offices, military, industrial, residential, heritage and aged care. What to include? What to reject? Troiani has adopted the democratic strategy of presenting twelve projects: one for each decade of the practice. This in itself must have presented enormous difficulties. For example, the first project to establish the firm – the Brisbane Head Fire Station, won in competition in 1889 by Government architect Henry Wallace Atkinson – is an obvious beginning, but its inclusion precludes Keith Frost’s Kemp Place Fire Station from the 1960s.

The exhibition’s presentation of the first six decades demonstrates an adherence to style revival: projects include the robust neoclassicism of the Trades and Labour Hall (1919) by Charles McLay, and the Spanish Mission style of Craigston Apartments (1928) by Arnold Henry Conrad. Mangus Hall at the Church of England Grammar School, designed in 1949 by T.B.F. (Bren) Gargett as part of a group of buildings begun in 1935, is selected as the 1940s example. With its dominant gable roof form and articulate red brick base, it owes copybook allegiance to the Arts and Crafts and the English Freestyle of Voysey and Shaw, but it has a confident presence that has easily allowed more recent additions to unselfconsciously add to a campus of fine buildings.

The second six decades is organized to show the opening up of the practice to a more overtly modern idiom. Notable projects include the Women’s College at the University of Queensland (1958), also by Frost; and Block 7, Royal Brisbane Hospital (1968–1977, the continuation of large government commissions for hospitals); as well as commissions for banks – Head Office, Commonwealth Bank of Australia (1989); and insurance companies – SGIO Office Building and Theatre (1971).

For such a vast output, this is a small exhibition. It is housed in just one of the bays at QUT Art Gallery. Almost domestic in scale, this provided Troiani with another challenge. She has overcome this tight space by augmenting the twelve elegantly designed panels (one for each building/decade) with a short fourteen-minute film. Made in collaboration with photographer and editor Shaun Charles and composer Paul Hankinson, the film previews ten of the presented buildings, intercut with interviews of recent and current directors and former clients. These interviews explain the work and give the exhibition a tangible quality that would have otherwise been precluded by the modesty of the display.

The film is interesting in its methodology. There is no interlocution – a role Troiani could have played as researcher and critic – architects, clients and buildings “speak” for themselves without commentary. This mode of interview/recording as a non-mediated form of inquiry stems from Troiani’s doctoral research into the culture of practice and has previously been successfully employed in Building Mayne Hall, a longer film made in 2004 exploring the circumstances surrounding the procurement of Mayne Hall at the University of Queensland.

The modesty of the exhibition would be a minor quibble if it were not for the paucity of this kind of public engagement with architecture in Brisbane. Since Don Watson curated Well Made Plansat Brisbane City Hall Gallery in 1988, there have been as few as six or seven public exhibitions of architecture. For example, last year,Wilson Architects, that other long-lived local architectural institution, presented an overview of their art practice, mostly paintings with tiny glimpses of some recent buildings, at the University of Queensland’s James and Mary Emelia Mayne Centre (formerly Mayne Hall, designed by Wilson Architects). Prior to this Andrew Wilson (no relation) curated an exhibition of the work of Hayes and Scott in 2002 and his Birrell project travelled from RMIT to Brisbane City Hall Art Gallery in 1997. There has also been architectural content in exhibitions on broader cultural subjects at venues such as the Museum of Brisbane, but little else gets serious exposure.

In contrast, John Murphy’s recent Sydney Opera House exhibition at the Museum of Sydney is bolstered by the kind of support – financial, curatorial, but above all intellectual – that Troiani could only dream of. Utzon deserves this pre-eminence and John Murphy and the Museum of Sydney are to be congratulated for this sophisticated retrospective. However, if we as a profession seek to broaden the debate on architecture and advocate the enhancement of the built environment we need more than the lavish, albeit appropriate, celebration of an iconic building already well established in the nation’s psyche. Igea Troiani’s exhibition and film warrant close inspection. They hint at how we might appreciate local architectural practice, in a manner that has a regard for care and thoughtfulness in the making and the occupation of architecture. This deserves more detailed exposure and discussion.

DOUGLAS NEALE IS AN ARCHITECT AND ASSOCIATE LECTURER IN ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND. HE WAS AN EMPLOYEE AT CONRAD AND GARGETT ARCHITECTS BETWEEN 1988 AND 1995 AND RETURNED BRIEFLY IN 1998 BEFORE HIS APPOINTMENT TO THE UNIVERSITY OF QUEENS