CALLUM MORTON’S ART PRACTICE USES HUMOUR TO INTERROGATE QUESTIONS OF FUNCTION AND ARCHITECTURE. SUSAN BEST REVIEWS HIS EXHIBITION OF ANIMATED MODELS AT THE MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART.

Gas, 2003, transforms Philip Johnson’s Glass House into a service station. View of model installed at the MCA.

International Style Compound, 2000, derived from the Farnsworth House, installed at the MCA. Photographs Greg Weight, courtesy of the artist and the MCA.

Cabanon and on and on… 2002–03. Photograph Richard Crompton, courtesy of the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne.

Oh Brigitte 2001 (detail). Collection of Anna and Morry Schwartz. Photograph Richard Crompton, courtesy of the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery.

Untitled, 2003 (with Nick Hubicki), installed at the MCA. Photograph Greg Weight, courtesy of the artist and the MCA.

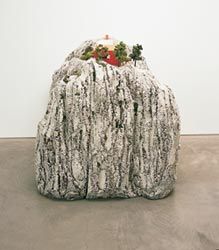

Habitat 2003, installation view at the National Gallery of Victoria. Corbett Lyon and Yueji Lyon Collection. Photograph Helen Oliver-Skuse, courtesy of the artist and the National Gallery of Victoria.

THE RICH SEAM BETWEEN art and design is now being explored by a new species of practitioner called “design-artists” or “artist-designers”. Practitioners working between these two areas include Andrea Zittel, Jorge Pardo and Joep van Lieshout. It is this new category of practice that best accommodates the work of Callum Morton. Sitting between architecture and art, his work reflects his training first as an architect and then as an artist.

Morton has previously worked in a site-specific mode, adding redundant structures to existing exhibition spaces – structures such as balconies with apparent access provided by fully detailed doorways. These earlier works often circled around the rhetoric of architectural function in subtle and humorous ways. For example, the balconies appeared functional by dutifully following the architectural language of the site. Melding with the space in this way, they seemed to camouflage themselves, to disguise their status as surplus to requirements, as non-functional additions.We learn much here about the power of architectural language: mimicking the language of the site can give spurious additions authority, a claim to be functional, as it were. The Modernist concern about the essential versus the ornamental can be bypassed if the “ornament” sneakily deploys the correct language. Indeed, the deployment of the deadpan language of institutional architecture almost convinces us to accept the nonsensical appearance of an external structure inside. Almost, but not quite. This authority was undercut by the subtle humour of the additions – why would an exhibition space need a balcony? Where is the view? Or perhaps, the question turns around on the viewer at this point, positioned precisely in the position of the viewed.

The current exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, Callum Morton: More Talk about Buildings and Mood, does not include site-specific works; instead it is comprised of architectural models. Some of the buildings are instantly recognizable: the United Nations tower in New York which now constantly flashes across our television screens, the Farnsworth House and Casa Malaparte. Others are perhaps less well known – Le Corbusier’s cabin at Cap Martin, Captain Cook’s cottage, a housing complex in Montreal by Moshe Safdie – or less immediately recognizable, Philip Johnson’s Glass House is transformed into a service station.

The function of architecture is again a key question addressed by these works, only this time function is aligned with the accommodation of life. Morton’s project could be summarized as trying to show this function by breathing life into the architectural model.

The idea is an exceptionally good one: architectural models, no matter how accurately they represent a building (and perhaps this perfection is precisely the problem), are a remarkably lifeless form of representation. For the non-architect (and I’m really speaking for myself here) it is extremely hard to imagine the building when presented with the model. The title of this exhibition, “buildings and mood”, identifies precisely what I think architectural models lack: tone, mood and expressivity.

Morton installs light and sound into architectural models, often creating an interesting dissonance between the perfection of the models and the irreverent activities they accommodate. In some works he also tries to recapture something of the history of the buildings. For example, the Casa Malaparte model, Oh Brigitte (2001), in both its title and soundtrack recalls the film made by Godard, which used the building as a setting. The film starred Brigitte Bardot as the disgruntled wife of a screenwriter and ended with the word “Silenzio” (which periodically issues from the model).

Similarly, Cabanon and on and on (2002–2003), the model of Corb’s cabin has the sound of a heartbeat proceeding to cardiac arrest. The wall text tells us that Corb died of a heart attack in this cabin, although a more reliable source, the architectural historian Beatriz Colomina, claims he went down to the sea from Eileen Gray’s house E.1027 and swam to his death. The interesting and scurrilous history of the building – its rivalrous relationship to Gray’s house above which it was built – appears in the wall text but unfortunately isn’t incorporated into the form of the work. In fact, in many of the works the wall text is doing a lot of the work. I kept wishing the ideas were incorporated into the works, rather than narrated as the context or set-up for the visual and aural gags. I also kept wishing for the more subtle humour of the earlier work rather than the one-liners that seemed to dominate this exhibition.

The most disappointing work in this regard is Untitled (2003), a model of the UN headquarters from which issues the sounds of children playing war games. This repopulation of the building with childish games seemed a rather cheap shot. Turning the work of the UN into petty schoolyard fights doesn’t offer much insight into the building or the UN. On the other hand, the most engaging work in the exhibition, the housing complex Habitat (2003), is a very insightful interrogation of the building, which deploys gentle humour rather than relying upon an obvious gag. This work approaches the condition of film by using sound and light to convey a sense of duration – the work compresses a day in the life of the complex into a half-hour sequence of changing lights and sounds. With this work, one starts to realize how much can be conveyed by sound and light.

For example, sounds represent both the individual activities of particular occupants and the shared rhythms of daily life. The sound of synchronized ablutions as the occupants get up, and then again when they go to bed, and the thundering sound of feet on the stairs leaving for work and returning, are amusing evocations of lives bound together by time rather than a more noble ideal like communal life. Light is also used in two different ways: to represent the individual lives of apartment dwellers – a light comes on in an apartment accompanied by a specific sound – and in a non-representational way as if connoting the life of the building.

The non-representational sequences of flashing red, green, yellow and blue lights suggest a dynamic Mondrian canvas, as though the complex was conceived, in the absence of the occupants’ activities, as an abstract work of art. This dual use of light is a very subtle way of drawing attention to the gap between architectural ideas and their lived reality.

On the whole, this is an enjoyable show and I’m sure architectural insiders, who are not as dependent upon the wall text to get the joke, will have a lot of fun with the irreverent humour. However, the more serious issues about architectural function and representation, also broached by Morton’s models, were mostly not well served by the gag-format, which tended to terminate contemplation with “I get it”, rather than stimulating further reflection.

Perhaps humour needs more bite to serve reflection. The humour in this exhibition largely turns on bringing the high low: an architectural icon like the Glass House becomes a gas station, the Farnsworth House is duplicated four times to suggest project homes, Cook’s historic cottage hosts a lusty romp, the UN becomes a schoolyard. Habitat, however, suggests a more layered and complex answer to the problems of adding mood and humour to lifeless models. I hope Habitat, rather than the UN building, represents the future direction of Morton’s work.

DR SUSAN BEST IS A SENIOR LECTURER AT THE SCHOOL OF ART HISTORY AND THEORY, UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES. CALLUM MORTON: MORE TALK ABOUT BUILDINGS AND MOOD SHOWS AT THE MCA, SYDNEY, UNTIL 26 JANUARY.