Images from the Stephenson & Turner Archive, which forms the basis for the exhibition. Long Room, Melbourne Cricket Club, Melbourne Cricket Ground, 1927, by Stephenson & Meldrum. Gelatin silver photograph by Commercial Photographic.

Australian Pavilion, New Zealand Centennial Exhibition,Wellington, NZ, 1940, by Stephenson & Turner. Gelatin silver photograph by Russell Roberts.

Porte-cochére at the main entrance of the King George V Memorial Hospital for Mothers and Babies, Camperdown, Sydney, 1941, by Stephenson & Turner. Gelatin silver photograph by Milton Kent.

Patients on the balcony ward at the Children’s Orthopaedic Hospital, Frankston, 1936, by Stephenson & Meldrum. Gelatin silver photograph by Commercial Photographic.

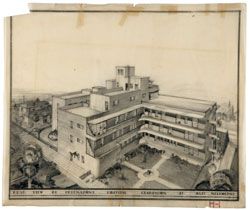

Perspective of the rear of the Freemasons Hospital, Clarendon Street, East Melbourne,1936, by Stephenson & Meldrum.

THE STAGING OF architectural exhibitions is often problematic because they are generally not considered (in Australia at least) to hold sufficient public interest to attract an audience. Thankfully this appears to be changing and there has been a wave of exhibitions about architecture and architectural photography around the country in the last year. This is in part due to a renewed interest in architectural histories, particularly local ones, and to the ever-wider acceptance of conservation. Exhibitions and catalogues can play an invaluable role recording buildings and places and interpreting archival documents in ways that may help to shift the sometimes bankrupt debates surrounding preservation or demolition towards conservation through scholarly documentation and public education. (The international conservation organization DOCOMOMO has as its primary aim just this: the conservation of modern movement places and buildings via documentation.) The increased prominence of exhibitions is also due in part to institutions such as universities and libraries now lending significant support and recognizing the value of this form of architectural research.

The current exhibition at the State Library of Victoria, Australian Modern: The Architecture of Stephenson & Turner, is the most recent example of the value of the didactic historical exhibition. It draws on the archive of the firm’s work, which was given to the State Library of Victoria in 1994. This is the largest of the library’s architectural collections, containing some 283 drawers and over 200 tubes of drawings, 15 boxes of photographs, and 389 metres of specifications and correspondence.

Curated by Rowen Wilken, the exhibition is ordered around two themes of health and prosperity and a chronology of the firm’s output. A number of types of images are displayed including presentation photographs and sketches, site plans, working drawings and details. (A favourite is the detail for a soap tray, towel rail and smoker’s tray of 1941.) Choosing a mode of exhibition for such a range of representations that had quite different original purposes is always a dilemma. Here, they are displayed in a fairly conventional way – neatly framed “originals” elegantly and sparsely arrayed on white walls. The result is coherent, informative and accessible for a wide public audience. This is the right curatorial position for the venue of the State Library, but many other aspects of this immense archive could also be explored and displayed – like the messy and contingent process of architectural production from sketch to completed building, and the materiality of the types of architectural documents in the archive.

This physicality of both documents and process is rather cleaned up by the formal framing.

The accompanying catalogue is written by Philip Goad, Rowen Wilken and Julie Willis, and published by Miegunyah Press in conjunction with the State Library of Victoria. The fine quality of the individual essays and the image production, in an elegant grey tone, elevates the catalogue to a substantial and lasting publication. The book is meticulously referenced and provides essential additional information for future research including an extensive selection of images, a key buildings reference, an exhibition checklist, selected bibliographies and catalogue notes. The inclusion of full-page photographs to break up the sections of the book goes some way to convey the faith in modernity inherent in a number of the buildings. (Although it is a shame to interrupt the archival value of these fantastic photographs with title overlays.)

Rowen Wilken’s opening essay “For Health and Prosperity: the Colossus of Australian Architecture” provides a general introduction to the output of Stephenson & Meldrum (1921–1937), followed by Stephenson & Turner, across a number of fields including health, commerce, education, residential and exhibition buildings. At its peak Stephenson & Turner was the largest practice in Australia with some 300 to 400 staff in many offices across Australia, Asia and New Zealand. Architectural production on this scale is by no means a singular effort, and Wilken acknowledges, both in the essay and the exhibition interpretation, the strong input of many individuals over the years, including a number of women.

The subsequent essays, like the exhibition layout, develop the two major spheres of impact of Stephenson & Turner’s work: health and prosperity. The second essay, “The Health of Modernism: Expression and Efficiency in Hospital Architecture 1955–1967” by Julie Willis, is an important account of the pivotal role Stephenson & Turner played in the development of hospital and healthcare architecture in Australia and internationally. Willis outlines the reciprocal relationship between innovations in healthcare knowledge and practice and the language of Modernism, and figures this as critical to understanding broader trends in twentieth-century architecture in Australia and elsewhere. The images reproduced in the essay illustrate the direct effects of Stephenson & Turner’s research travel on Australian healthcare design. For example, on his 1932–33 trip to Arthur, Stephenson was particularly impressed with developments in European Modernism including the work of Mendelsohn, Aalto and Döcker.

This essay could easily be the subject of a larger account that would tease out many issues – including the tantalizing statement, “If Le Corbusier built houses that were ‘machines for living’, Stephenson & Turner built hospitals that were machines for healing.” ›› And although it is perhaps a relief not to find the almost obligatory references to Michel Foucault’s The Birth of the Clinic, it would be revealing to locate the firm’s hospital oeuvre in a broader spatial history of twentieth-century health technologies, and the changing relations between patient and expert. In a topical aside, Willis also describes how Stephenson & Turner were invited, alongside Walter Gropius and Frank Lloyd Wright, by the Kingdom of Iraq to advise on modernizing their infrastructure in the late 1950s. It would be intriguing to follow the fate of such Modernist structures in Iraq today and the current attempts by a European group of conservation architects to document them.

Philip Goad’s essay, “The Business of Modernism: Propriety and Process in Corporate Architecture”, charts the growth of the firm’s commercial work and client base from the modest beginnings of Stephenson & Meldrum’s alterations to Collins Court and the Wattle Tea Rooms (1921), to large-scale commissions in the 1960s including the Colonial Mutual Life Assurance Building (1963) and the IBM Centre (1962–64). He examines the delicate balance sought between the constant quest for technical and pragmatic innovation, and the longstanding sense of architectural propriety towards the continuity of the urban context.

The catalogue locates the firm’s work within the broader themes of modernization and progress in Australia. Hence the term “Australian Modern” is coined to reinforce the significance of Stephenson & Turner’s architecture, which – as both Robin Boyd and Goad suggest – has almost been overlooked because of its very ubiquity. That is not to say that Stephenson himself was not recognized for his achievements in hospital design, recognition which culminated in his being awarded the Royal Institute of British Architects’ Gold Medal in 1954 – hot on the heels of Le Corbusier, the previous winner.

Australian Modern provides a great model for potential collaborations between the resources of state libraries and architectural researchers across the country. This exhibition and catalogue give, both together and separately, an accessible account of the work of Stephenson & Turner. As the authors readily acknowledge, many aspects of the archive remain unexamined. For example, further investigation into Stephenson’s travel could reveal a lot about how architectural exchange and influence operated in the mid twentieth century, both interstate and between Australia, the Americas and Europe. The power of any public visual archive for telling stories about ourselves has been dramatized in Stephen Poliakoff’s play Shooting the Past in which he writes of an enormous photographic collection that is in danger of being broken apart. The argument is poignantly mounted for holding the collection together through the unique possibility of making endless and serendipitous connections between images that will allow for any number of future historical stories to be told. Similarly, due to the immense size of this archive of built history, there are many subsequent interpretations that may be made around the fluctuations of future historical and conservation interests.

DR HANNAH LEWI IS A SENIOR LECTURER IN ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE.