Prompted by a recent exhibition, Peter Moran reconsiders the oeuvre and contribution of Julius Elischer.

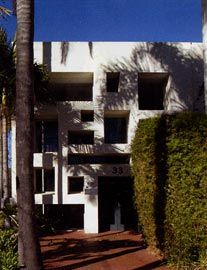

Foulkes-Taylor showroom, 1964.

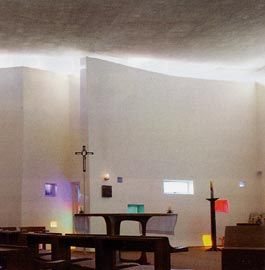

Wollaston Anglican Chapel, Mt Claremont, 1964. Images: Robert Frith.

Lisle and Leaweena Lodges, Mt Claremont, 1978.

Branchi House, City Beach, 1969. Images: Michael Bradshaw

A recent picture book of Australian architecture, Austral Eden by Patrick Bingham- Hall, includes three postwar buildings in Perth: Ferguson, Clifton and Brand’s Brutalist Hale School Memorial Hall, a sculptural concrete block house by Iwan Iwanoff and a small 18 x 14 x 7 metre white masonry box designed in 1964 by Julius Elischer. But this furniture showroom for David Foulkes-Taylor is not an isolated piece. It is the more salient of a series of characteristic white thick-walled structures undertaken by the émigré Hungarian architect after he commenced practice in Perth in the early 1960s. The recent exhibition Julius Elischer Architect: Selected Projects 1958-1985, curated by Michael Bradshaw and Simon Anderson, and the accompanying catalogue edited by Kate Hislop, brings this work into the public realm once more, and provides an opportunity to reconsider Elischer’s contribution.

Postwar architecture in Perth was a period of new beginnings and this was reflected in the adoption of Modern architecture after the mix of traditionalism and Deco of the inter-war period. The Modernist work of local practitioners who had been educated, travelled or gained experience overseas was sharpened by the impact of European émigrés like Iwanoff and Elischer. In Elischer’s case, the transplanted threads of rationalism and formalism were rendered in his buildings in complex and often unexpected ways through a reflexiveness to site and a mastery of brief.

Born in 1918 in Budapest into a professional family background of medicine, the arts and architecture, Julius Elischer’s architectural education and postgraduate studies were interrupted by the later stages of the European War. Displaced from Hungary, he worked in Germany on reconstruction projects and competitions, before immigrating to Melbourne in 1951. Coming to Perth with Stramit in 1957, Elischer decided to remain and he worked as an architectural draughtsman. After a stint teaching design at Cornell in 1963 (on the basis of a 1950 competition win while still in Germany), he returned to Perth to register as an architect and formally open his practice. He retired in 1986, though his staff continued the office until 1991. Now 85 years old, he gave a short and moving speech at the opening of the exhibition.

Apart from his practice, Elischer was also involved in architectural education and maintained wider interests in the construction industry. He developed lightweight panel systems, took out various patents and was a joint partner in a prefabrication business with activities in remote WA, South-east Asia and at one point Africa. As an architectural student at UWA in the latter half of the seventies, I had Julius as year convenor for two of the five years of the course. My relationship with him was ambivalent. He avoided intellectualizing and was exasperated by the preoccupations of the time, later labelled “post-modern”. It was easy, then, to stereotype him as a narrow Modernist.

In retrospect, as the exhibition makes clear, this stereotyping was sustained only by an incomplete appreciation of his work. Indeed, connections can be drawn between it and the critical concerns of the seventies – although Julius himself would not have made these links himself. For example, knowledge of the Yokine Baptist Church (1971), a raised box with an enormous super-graphic JESUS SAID I AM THE WAY on the street elevation, would have prompted a conversation about Venturi’s Learning from Las Vegas – and this wasn’t an isolated coupling of “signifier” and “shed”. Equally, an understanding of the Wright House (1976) and the later churches would have initiated other lines of discussion – maybe Haring and Scharoun, certainly Aalto. Sufficiently encouraged, this discussion might have expanded to include Demetri Porphyrios’s use of Foucault’s homotopic/heterotopic distinction in his analysis of Aalto’s work. Christopher Alexander’s Pattern Language may not have fared so well. However, Alexander’s injunction to work directly with the site, engaging the full range of the human perceptual apparatus within a holistic empirical framework, may have struck a deeply sympathetic chord.

Alexander attacked the abstract formalism of Modernism. In his architectural work Elischer always sublimated the instrumental to the experiential. This is particularly significant given his other interests – engineering patents, actual ownership of a prefabricated building company – and the orthodoxies prevalent among other architects of the time. Elischer always deployed surface, mass and enclosure, with an awareness of the sharp qualities of Perth light.

Frequent structural and construction ingeniousness was not paraded, but removed from the experience of the buildings. Technique, like drawings, was a convenience, predicated by economy. Differentiation of material was suppressed. The work was sculptural and intuitivethough a specific modernist sensibility and vocabulary of forms mediated this intuition.

The tension with rationalism was in the sensitivity to context – be it the “commercial strip” or the suburban fringe, like the knoll at the centre of the site for the Wright House. This project illustrates how Elischer increasingly sought to build in the landscape. Moreover, he actively “built site” on Perth’s sand plain, amplifying and exaggerating levels. Frequently massive retaining walls were used to create elevated plinths for his residential projects, accommodating raised terraces for outdoor living in Perth’s “mediterranean” climate. In his introductory essay for the catalogue accompanying the exhibition, Simon Anderson draws the following conclusion: “Julius Elischer’s view of modern architecture is different to those of the historians of architecture, and to those of most other architects. His architecture’s great and lasting contribution is above all else the primacy it places on the site as a physical and cultural generator of form and space.” ›› The Elischer exhibition is part of an ongoing informal series on the work of postwar Modernists that has so far covered Howlett, Summerhayes, Finn, Krantz & Sheldon and Overman. The series provides the opportunity to review much important and neglected work.

Large format drawings, extracted from the archives of the respective offices, have formed the core of these exhibitions. As such they have been of interest as much for their form as for their content. There are some issues with legibility when these large drawings are compressed to suit the relatively small format of the accompanying catalogues. Nonetheless, these little booklets are an important, and at this stage almost singular, resource on postwar work in Perth. In Elischer’s case, the catalogue coverage is supplemented by a project chronology, providing the means for a fuller examination of his work. This list focusses on the recognized “architectural” works and, as such it continues the architect’s own apparent distinction between the tasks of “architecture” and those of utilitarian “building” (in his prefabricated work and related patents).

The project listing is also useful because Elischer is an architect who repays close study, at all levels, including that of detail. An interesting instance was his exploitation of Perth’s “double brick” tradition and his breaking of the tyranny of its 270 mm overall width with his characteristic “thick”, white painted or rendered, load-bearing walls. Aesthetic and structural requirements were met by expanding the brickwork wall cavity. Internal piers, achieved simply with bricks bedded in DPC bonded through both leaves, provided stability. There were no (uneconomic) steel columns or complex flashings. Expansion joints in the brickwork panels were treated as glazed slits, sometimes incorporating louvres for ventilation, with the ends of the two leaves offset so that the interior surface could be gently washed with reflected light.

Elsewhere, punched openings had deep reveals to similarly soften the impact of Perth’s harsh sun. The expressive possibilities of these simple ploys were most poignantly realised early in the iconic Foulkes-Taylor showroom. It will no doubt remain Elischer’s most well known and, in a sense, complete work. However, as this exhibition reveals, for Julius this building was not closure but a departure and the beginnings of significant contribution to Modern architecture in Western Australia.