Installation view of Built showing Narelle Jubelin’s Soft Shoulder (1994) and Callum Morton’s Monument #23: Slump (2009).

Installation view. Works from left to right are by Lucas Jodogne, Stephen Bush, Narelle Jubelin, Sam Durant and Kate McMillan.

The other side of Callum Morton’s Monument #23: Slump (2009). Installation view at Roslyn Oxley 9 Gallery, Sydney, 26 February – 21 March, 2009.Photograph Ivan Buljan.

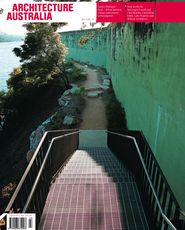

Alongside the usual touring and one-off exhibitions, recently the Art Gallery of Western Australia has been exhibiting what it calls “dynamic presentations” of its permanent collection. Succinctly titled with names such as Body, Mapping, Home and Presence, their clever curatorial organization gives a reason for multiple returns to the gallery, and also makes connections between new and more familiar pieces from the gallery’s permanent collection. James Angus’s fantastic conjoined-twinned Bicycles (2007) and South African photographer David Goldblatt’s tender Particulars (1975–85) – closely cropped photographs of bodily gestures taken without his usual searing eye – are among some of my favourite discoveries from these exhibitions. One of the most recent of these shows to open is Built, organized around the gallery’s recent acquisition of Callum Morton’s Monument #23: Slump (2009).

Morton’s work is a large double-sided insertion in a side gallery, whose “back” is visible from the central circulation space of the gallery. The work literally slumps towards the viewer, a faux blockwork wall, held up by temporary props and sandwalls, sagging under an unknown weight. On its reverse side, brise-soleil are convincingly rendered as collapsing, shadows precisely cast across their surface towards the folds in the slumping wall. This is one of a number of works by Morton that engage with the specific legacy of heroic modernity. The modernist objects that litter Morton’s work – Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh, Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House, Harry Seidler’s Rose Seidler House – actually don’t need the artist’s help to point out their failings. The Farnsworth and Seidler houses are now owned by historic house trusts, as museum pieces to be restored and protected. The Farnsworth was previously owned by Lord Peter Palumbo, whose collection of modernist buildings included Le Corbusier’s Maisons Jaoul in Paris and a Frank Lloyd Wright house just down the road from Fallingwater. Modernity’s victory was so complete that it became what it sought to destroy; the bourgeois collecting culture that the museum represents and that modernity sought to demolish has absorbed its icons. Hal Foster describes this as modernism’s Pyrrhic victory, where the spoils of victory are outweighed by its losses. In this case, the utopian aspirations of the modernist project have become the flaccid backdrop to “lifestyle” – the Seidler house can be booked for fashion shoots or your special event. The plaza between Chandigarh’s High Court and Assembly is occupied by armed guards and the Tower of Shadows, its utopian space empty and sunbaked. In this context Morton’s work appears redundant, pointing out already self-evident truths. We killed those modernist heroes without his help (or did they kill themselves?). Where does that leave Morton’s work – an interesting trompe l’oeil, which tricks the eye and evokes a convincing sense of weight? A fragile Tilted Arc made of fibreglass and plastic that challenges you to see what is on its other side? Is it anti-heroic in a heroic way?

The curatorial pairing of Morton’s work with that of Narelle Jubelin is jarring. Soft Shoulder (1994) is a series of found and finely worked objects arranged along an enlarged mantelpiece that required closer attention, attention that was interrupted by the gallery’s security whenever the artwork was approached. While these delicate objects – engraved letters, framed multiple layers of what looked like text and gauze – remain distant from the viewer their impact is hard to register.

The second room of the exhibition avoids the awkwardness of the relationship between Morton’s and Jubelin’s work with a collection that builds on the relationship between ruin and order. Photographs by Lucas Jodogne and Anne Zahalka document an emptiness defined by the layered systems and histories of cities. Drawing on the lineage of New Topographic’s depiction of the urban environment, neither Jodogne’s nor Zahalka’s images are immediate; rather, they unravel their meaning through slow consideration.

For me it is these less bombastic works that suggest a more complicated relationship between the built environment and its use as a vehicle for creative endeavour. Concepts on the verge of collapse (2003), Kate McMillan’s survey of transient shelters built by homeless people in Tokyo, is matter-of-factly captured by her camera. Her images sit somewhere between a deliberate snapshot anti-aesthetic and images where the subjects are fetishized by the camera. McMillan’s photographs survey but they aren’t those of the anthropologist, exoticizing an “other”. Sometimes incomplete in their recording, they are taken as if in polite haste with a desire not to stare too hard. But the shelters are always located in a context, usually within the flows and eddies of urban life: public walkways, alleys and the edges of pavements. These images are tragic and complicated structures of record with a typology and construction language of their own. With the crispness of their tarpaulin folds the shelters can almost be read as stereotypically Japanese, but their thin temporality has a purpose that transcends their contingency. Set against the wealth of an industrialized and technologically advanced nation, their maker’s desire for shelter, order and fixity is made more poignant.

Curator Jenepher Duncan argues that the artists in this exhibition use the “representation of architectural form as a vehicle for creative enquiry”. As well as obvious formal, tectonic and spatial qualities of the built, this “vehicle” comes with a series of less well-defined qualities – social, cultural, political and even moral – that are able to be appropriated, exploited or questioned by the artist.

Instead of the representation of built form merely serving as a vehicle for artist speculation, this seems to disregard the potential of the lives of buildings, their occupants and their careful selection by artists. For example, Joanna Lamb’s meticulous paintings of suburban houses show her interest in the detailed recording of meter boxes, cranked down pipes and the fretted timberwork of their verandahs. While the seriality of the four paintings Flatland (2006) explores what the curator calls “sequential abstraction and colour perception”, these works aren’t what Duncan calls “featureless” in their perceived depiction of the “actual and metaphorical emptiness of suburban living”. Lamb has chosen a specific house in a specific location at a specific time – a modest early-twentieth-century worker’s weatherboard cottage which, like its neighbour, is set askew to the street, its shadow cast across its flat green lawn. It is the tension between the particularities of the house in its individual portraits and the abstraction of the house across the series that compels the viewer to search through and track every aspect of the house, to reconsider the everyday. Perhaps what annoys me is the laziness of the worn clichés – that suburbia equals moral, spiritual and creative emptiness, and that modernism equals failed dystopia. It is more complicated and interesting than that; these should be statements about art as well as architecture, compelling us to reconsider what is on the walls of the gallery and what is built around us.

Philip Goldswain is a lecturer in architecture at the University of Western Australia.

Joanna Lamb Flatland (Figure A-D) (2006). State Art Collection, Art Gallery of Western Australia. Purchased with funds from the Contemporary Art Group, Art Gallery of Western Australia Foundation, 2006.