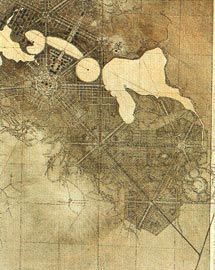

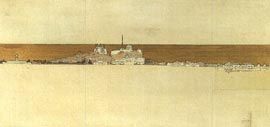

Detail from the City and environs drawing. NAA: A710, 38.

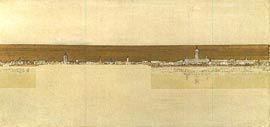

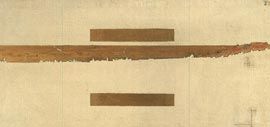

Section A-B, northerly side of the water axis. NAA: A710, 39-42.

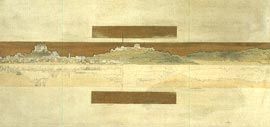

Section C-D, easterly side of the land axis. NAA: A710, 44-47.

View from the summit of Mt Ainslie. NAA: A710, 48-50.

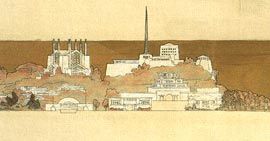

Detail showing cathedral and military college. NAA: A710, 45.

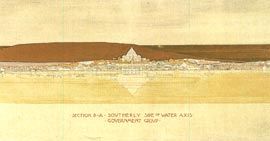

Section B-A, southerly side of the water axis. NAA: A710, 43.

A Vision Splendid, at the National Archives, publicly displays the full set of the Griffins’ drawings for Canberra for the first time since 1917. A number of the drawings on show are well known through publication and other forms of reproduction, and many architectural viewers will be at least partly familiar with the content of the images. Yet the visceral quality of ink, dyes and gold on satin cannot be reproduced. To see these things “in the flesh” is an exquisite and moving experience.

The drawings were produced through a complex and exacting process that is outlined in the accompanying catalogue.

Marion Mahoney Griffin made them initially with a quill pen in ink on linen, these were then lithographed onto “window shade holland and rendered with watercolour and photograph dyes”. These drawings were in turn lithographed onto satin, which was then dipped into thin blue size and stretched on board. When dry the drawings were rendered, removed from the board and lightly dusted to remove enough size to reveal the satin surface. This labour and care, the bodily work and the light touch required in their making, have all in some way marked the drawings. Despite frequent reproduction, these objects retain a palpable aura.

Archives are hushed places where one carefully encounters the material object, often while searching for more abstract kinds of information. Researching, one sits, white-gloved, for hours; the boredom of sifting always tempered by the possibility of the thrill of discovery. The archive is a place of contemplation and consideration. The exhibition is an altogether busier environment, where much of this sifting has already been done. But the curators and designers of A Vision Splendid have used the exhibition to convey both this sense of discovery, and the idea that the story is constructed from archival documents – from minutes, memoranda, and other traces of institutional and personal activity. The exhibition uses this material to locate the drawings in broader social and political contexts. Quotations from a wide variety of documents are used liberally to convey the fate of the Griffins’ “vision” at the hands of Federal bureaucrats. The accidental marks that have accumulated on the drawings over the years are also used to tell the story of the drawings. One caption draws attention to an inkblot, which was not apparent in the early photographs of the drawings. Was this, the caption speculates, the result of an irritated official waving his pen around?

This interpretative material seems successful in actively engaging the visitor.

When I visited, others were also poring over the drawings, comparing them to the Canberra they knew, but even more people seemed fascinated by the political machinations that surrounded the realisation (or not) of the design. Yet the interpretative panels seem cluttered and over-designed – especially when compared with the sparse lushness of the drawings themselves. This clutter is standard fare in contemporary exhibition design, but it is still disappointing.

A similar aesthetic is at work in the catalogue, where it is more restrained and much more successful.

The drawings intrigue both from a distance and close up, where the finely detailed grain of the proposed built fabric is absorbing. But the layout of the exhibition is also slightly frustrating. There is nowhere to sit quietly and look; nowhere to contemplate at length the richness of these remarkable drawings. A large column also impedes any overall view of the panoramic series of sectional drawings.

The exhibition publicity describes the scheme as Walter Burley Griffin’s design, drawn by Marion Mahoney Griffin. This ignores the complexity of collaborative endeavour and assumes that drawing has no inventive or generative power. Unwittingly perhaps, this material reinscribes a whole series of assumptions, gendered and otherwise. These cliches are something that the catalogue essay, a wide-ranging, intelligent and accessible piece by Christopher Vernon, assiduously avoids as it carefully acknowledges design as a collaborative activity.

This exhibition has turned out to be the most successful ever mounted by the National Archives and while these drawings and the surrounding tale have a special place in the hearts of many architects the lay exhibition-goer seems equally captivated.

Seeing them is indeed a splendid thing.

Justine Clark is assistant editor of Architecture Australia. A Vision Splendid: How the Griffins Imagined Australia’s National Capital is on display at the National Archives, Canberra, until 29 September 2002