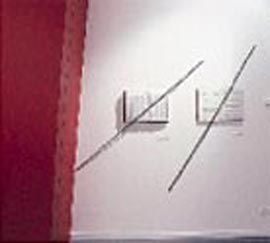

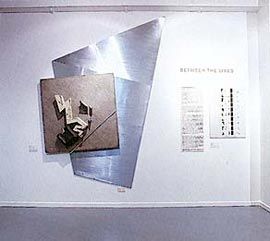

Black steel bars pin the Gedenkbuch and the score for Schönberg’s Moses and Aron to the walls of the Jewish Museum of Melbourne; both works were key to Libeskind’s Jewish Museum at the Berlin Museum.

Installation detail.

Jewish Projects at the Jewish Museum of Melbourne. Photos Garry Sommerfeld, courtesy National Gallery of Victoria.

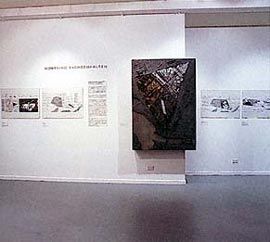

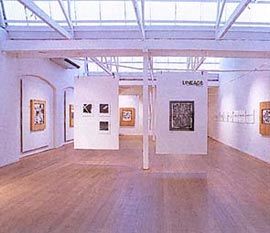

Drawn Projects at Span Gallery. Photo Trevor Mein.

Museum Projects at the National Gallery of Victoria. Photos Garry Sommerfeld, courtesy National Gallery of Victoria.

Where do you begin with an exhibition of complex work, called Lineage, staged in three locations by two institutions and a dealer gallery? To a certain extent, we each begin with what we know. My beginning was Chamber Works, a beautiful series of drawings that first captivated me when they made their way around the world as a boxed set in the mid-1980s. Span Gallery’s show of drawn works was the last exhibition I got to, but memories of Chamber Works haunted my visits to the Jewish Museum of Australia (Jewish Projects) and the National Gallery of Victoria (Museum Projects).

Chamber Works is a sequence of spatial explorations that deploys architecture’s most ordinary convention – black lines on white paper. However, here everyday lines and notational devices are freed from the imperative to represent directly. They spin, twist, swirl and stagger; strutting across the page, the dotted, dashed and ruled lines of architectural convention take on a new life.

To construct meaning the viewer must actively interpret.

In the exhibitions, these dancing lines seemed to be everywhere – both physically and conceptually. Formal links can be made between Chamber Works and some of the building designs but this is too easy. The drawn works are not simply patterns for making buildings; they are parallel architectural explorations, the traces of ideas and possibilities. As Donald Bates comments in his catalogue essay, “the line and lineage in the work of Daniel Libeskind is itself…multiple, twisted, returning and simultaneous”.

This is not to suggest that Chamber Works is the key to Libeskind’s oeuvre, but it does suggest certain modes of encounter.

Libeskind’s work (drawn, built or written) calls for active respondents. It demands that you bring things with you, and that you take things away. To quote one of the wall texts at the NGV: “If a museum is good then it continues to operate in the minds of its visitors after its closing hours. It continues to be an image which can be filled with dreams, analyses and thoughts…. But that is true of good architecture anywhere – it continues to be something that does not simply haunt in a negative sense, but instead gives a breathing room to speculate and to think of new ways of being.”%br% By spreading the exhibition across the city, the NGV and the Jewish Museum are engaging new audiences and forging new institutional and community links. Indeed, its staging at different locations reminds us of the different constituencies who might have a stake in the work, and of the different ways it might be framed. As a project, Libeskind’s Jewish Museum in Berlin has been part of the architectural landscape for years now.

But it is much more unsettling to examine it in Melbourne’s Jewish Museum than it is to see it while flicking through the pages of an international architectural journal.

In presenting this work both institutions are also engaging with their own futures and rethinking their pasts. The NGV is considering its own prospective directions, in line with contemporary rethinking of the role of museums. Lineage is also the NGV’s first architecture exhibition and signals that institution’s intention to present more architectural and design work in the future.

For the Jewish Museum of Australia, it is also about a different kind of future, and a much more direct engagement with the almost unspeakable past. Director Helen Light describes Libeskind’s work as a model of how to “draw indelible lines between the past and the future so that memory is retained and maintained as a bedrock on which to build a better world”. The Jewish collective memory, Light suggests, is charged with both remembering and reconstructing. “What kind of lineage,” she asks, “can be constructed that is respectful, healthy and enduring?” There are also other pasts to draw on in this remaking: “It is as if Libeskind has dragged the Jewish literary tradition into the 21st century; reinvigorating it, making it live anew…. Libeskind’s work thus points a way forward for Judaism in Germany, in Europe, beyond the Holocaust.”%br% Lab Architects designed all three exhibitions. Each one is simply organised, with drawings and text on the walls and models in the centre. The drawn projects were elegantly hung in Span’s simple white space. The two museum installations take cues from Libeskind’s own work – there are angled walls and irregular tilted stands for models. The beautiful boxed catalogue also alludes to Libeskind’s manner of presenting drawn and written work.

But it is disappointing not to have the drawn works and records of building projects somehow playing off each other more directly. Their separation suggests an artificial distinction. By showing projects like Chamber Works and Micromegas at Span, the drawn projects tend to be isolated as “art”, and become dissociated from their important role in architectural culture.

Exhibiting architecture is, however, always tricky. In the Jewish Museum and Span, the intimacy of the spaces works well with the intimacy of the drawings and models. The NGV’s installation is less successful. The mezzanine space in the Russell Street gallery seems to leak out over the much larger Versace show below, and the Friends of the Gallery space on the other side is distracting.

However, these are temporary spaces in a beautiful building.

Some of the projects displayed in Lineage appear more successful than others; nonetheless Libeskind’s optimistic belief that we might still use architecture to engage, and to help make a better world, is hopeful and compelling. But if Libeskind tells us anything it is that the relationship between past and future so not clear-cut. We do not leave the past behind when we move into the future.

Lineage is indeed a complicated thing.

Justine Clark.