View of exhibition installation with capitals made to Lucien Henry’s design.

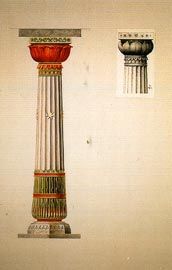

Waratah column, two types of capitals, watercolour by Lucien Henry.

The full-size “lyrebird” chair is based on one of Henry’s designs and was commissioned by the Powerhouse Museum in 2000 from International Conservation Services, Sydney. The exhibition displays it surrounded by designs for the room in which it was to be located.

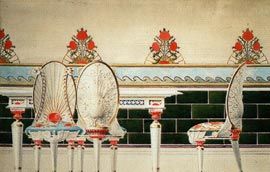

Chairs, table and dado, watercolour by Lucien Henry.

Fragments and objects displayed among Henry’s drawings at the Powerhouse exhibition.

Crematorium, Henry’s only surviving design of a complete building.

Visions of a Republic: The Work of Lucien Henry exhibits, for the first time, the late-19th- century decorative art produced in Sydney by this little-known French artist. At one level Henry’s work is informed by a concern with the antique and the significance of an archaeological recovery of a culture’s artistic heritage. But in the context of colonial Sydney, Henry was also concerned to provide the foundation of a yet-to-arrive Australian artistic culture.

A student of Jean-Léon Gérôme at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Henry was transported to New Caledonia aged 23 for his role in the defence of the 1871 Paris Commune. He made his way to Sydney in 1879, and spent twelve years in the colony as a teacher and practitioner of the decorative arts. His oeuvre consists of one hundred watercolour designs for applied art at various scales: from domestic objects, fittings and friezes, to columns, sections of public buildings and a spectacular crematorium reminiscent of Ledoux. The watercolours were completed as plates for a failed book project called Australian Decorative Arts, which was to show how a local design culture might emerge under the horizon of an independent South Pacific nation.

In the context of late-19th century Sydney, Henry’s work borders on the eccentric. His exuberant use of colour, and his incorporation of local plants in a way that maintained their idiosyncratic vegetal forms, shines through in what one imagines was a European’s delight at confronting never-before-seen nature. For Henry new expressive possibilities for decorative design emerged from the idiosyncrasy of the nature he found here. In its novelty, his work is reminiscent of decorative design from the turn of the 19th century, when the discipline and profession of interior decoration emerged for the first time in the publication of folios of designs from Charles Percier and Pierre Fontaine in France, and Thomas Hope in England.

Henry’s work sits well in this context due to its obvious classicism, but even more so because of the sense it gives that the classical is being observed with an archaeologist’s eye, as it was for these earlier designers.

It is worth speculating that Henry, in borrowing an aesthetic of the antique, wanted his work to be seen as recovered – as having already existed as objects before he came to represent them as designs.

Recovering an Order of the Waratah, or a lyrebird chair, as the artistic heritage of a South Pacific nation might focus its next phase of artistic development – that of the fine arts. Henry was explicit about this in one of only two articles he published on decorative art while he was in Sydney:

“It is only to be expected that the idea of an Australian Decorative Arts will be pooh-poohed by soi-disant connoisseurs, self-appointed artistarchs, who will find it, to say the least, very funny that, having received the new truths sifted out of the dust of the past, we are able to admire an earthenware jug, feeling that there is something more in it than the work of the potter; that behind the wheel, and the compass, and the potter, there is a national spirit which characterises a race and reveals to us its wants and its ideal.” ›› This statement had a peculiar resonance for my experience of the exhibition – an exhibition which attempts to show this very condition of “discovering” an Australian decorative arts as if one were visiting the archaeological site of its recovery. The exhibition is organised into themed rooms opening onto either side of a central axis.

The rooms are defined through poché. The implied thickness of the walls and the not-entirely- orthogonal relations between each space suggest that these rooms are themselves remnants of a much larger complex, the extent of which is occluded.

Two column capitals specially made for the exhibition from Henry’s designs stand at the end of the main axis, mounted as fragments; a lyrebird chair sits in a glass case surrounded by designs for a room within which it would have found its home; and a ceiling Henry designed for the Hotel Australia has been recreated. Fragments of architectural ornament are also arranged to show how such examples were used for design and drawing instruction, and a variety of exquisite display cases (rescued from the museum’s storage) round out the exhibition’s sense of inspecting the antique.

Yet the display of fragments and objects amongst Henry’s framed watercolours also reveals a tension between Henry’s projected images of a rediscovered antiquity, and the objects that might realise his “vision”. Although Henry was prominent as the first art and design lecturer at Sydney Technical College, the selection of objects showing the use of local flora and fauna in slightly later decorative art merely shows an idea adrift in a fashion-oriented art nouveau, or a banal faux-contextualism. The trajectory of Henry’s teaching seems to have been folded back into the South Kensington model of design education received at the periphery of Empire. Although Henry advocated something similar to the South Kensington model in his teaching, he did so from a position where his very eccentricity and his French republicanism heralded different possibilities in the South Pacific.

Henry saw how the currency of his work might be delayed, and that its meaning might emerge in the way it is called to witness an age when a South Pacific nation might feel the urge to realise itself as a republic. In providing “visions of a republic”, we really must read them as deferred visions, and then only, in Henry’s manner of thinking, as an antiquity which we can acknowledge and from which we move on. It is thus not mere opportunism, nor an overtly political statement, for the Powerhouse Museum to have planned this exhibition for a date when an Australian republic might have been a reality, but when its mature artistic culture stems from an indigenous art in a vastly-changed contemporary scene.

Charles Rice is a associate lecturer in architecture at UNSW. Visions of a Republic is at the Powerhouse until October 14.