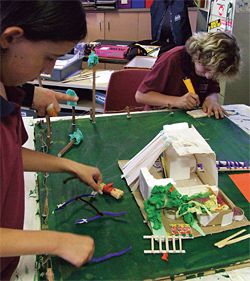

Models from the Eco-Cubby exhibition, created in collaboration between architects and schoolchildren.

The University of Melbourne Early Learning Centre’s cubby. Architect Mat Foley.

Alphington Primary School’s cubby. Architect Andrew Smith.

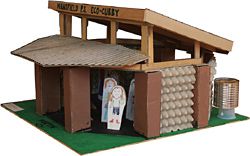

Mansfield Primary School’s cubby. Architect Charlotte Lindsay.

Bundalaguah Primary School’s cubby. Architects Kirsty Fletcher and Jon Pye.

Children, sustainability and architects. Clare Newton discusses the Eco-Cubby program and recent exhibition.

There is a fine tradition of architects and architecture students working with schoolchildren to explore aspects of the built environment. The Australian Institute of Architects has been proactive over the decades in supporting collaborations with schools in programs such as the Built Environment Education program (BEE). Such collaborations were particularly thriving in the seventies. As well, schools were often willing recipients of free labour provided by architecture and construction students, who built and landscaped play spaces in schools as the hands-on component of early university subjects. As a Melbourne architecture student, I remember disappearing from my course for a couple of weeks to go interstate to help construct a Gaudíesque playground, developed and built as a collaboration between an architect (Morrie Shaw), willing architecture students and an enthusiastic group of primary school students.

The latest Australian collaboration between architects and schoolchildren, called Eco-Cubby, is a pilot initiated by ArtPlay and others at the City of Melbourne in partnership with Regional Arts Victoria. The intention was to take sustainability concepts into the classroom. The Institute supported the project with a call for expressions of interest, matching ten architects with ten schools across Victoria, many located in drought-affected rural towns. Strategically, the brief was kept open. Project coordinator Kelly Boucher said, “We didn’t put too many restrictions on the architects and schools.” Stage 1 of the brief asked architects to share principles of sustainable living and building with schoolchildren while leading them through the process of designing and modelling an Eco-Cubby. In stage 2, the organizers aimed to assist schools to document and build the Eco-Cubby designs to support learning through play, teaching and creative arts.

The results of stage 1 of the pilot are exhibited in Melbourne’s ArtPlay Gallery (January 9 to February 21), a space devoted to promoting art for and by children and housed within a converted tramways shed next to Federation Square. Consisting of models, photographs and journals, the exhibition is a delightfully ramshackle collection interspersed with information panels about each project. One cubby is a sweet miniature house complete with verandah. Another school made use of a vast array of nearby recycled materials. Their cubby proposed tyres for the walls and “porthole” windows, with logs to support the roof and concrete culverts to collect rainwater. Three-year-old children from a city-based early learning centre worked with architect Mat Foley to develop a square, lightweight lookout space atop a contrasting cave-like, mud-brick cubby. Parents have raised funds and made mud bricks to ensure this cubby gets built.

The Eco-Cubby exhibition is in a small gallery curtained off from the adjacent larger activity space. It is disconcerting to visit the exhibition and hear squeals of delight from young children on the other side of the curtain, working on ArtPlay activities and oblivious to the delights of these doll-scaled models. The curtain protects the delicate models from the explorations of young hands. With more resources, the exquisite dilemma of visual access and physical protection might be better balanced.

The models in the Eco-Cubby exhibition each reflect different approaches to sustainability. Architects Kirsty Fletcher and Jon Pye helped primary students to visualize themselves in the models by getting the children to construct 1:20 plasticine models of their bodies. Their cubby became an interactive landscape made from a suite of mini models such as a secret tunnel, a garden plot, a graffiti art wall and play structures. Ed Ewers’ group made use of an existing shelter shed, adding rainwater tanks, gardens, a worm farm and outside seating.

A collection of cubbies by one school group was displayed on a wall at the exhibition. Julian Tuckett found that his students, from a citrus growing area near Mildura, were already savvy at building cubbies from bit and pieces in the paddock. The teacher encouraged the group to design a cubby that could be changed and reinvented by new students. A kit-of-parts approach was developed, with poles and shade sails. A school on the Murray River already had an enterprising group of children selling vegetables to the community from their productive garden. What they developed was a home for the chooks, a garden shed and a vegetable preparation area.

It could be easy for a visitor to this exhibition to see the haphazard collection of model cubbies on display and miss the joy and learning experiences with which these little environments were constructed. It could also be easy to dismiss the Eco-Cubby concept as an invasion of adults with a sustainability agenda overriding the simple pleasure that children gain from the construction of cubbies.

Using the cubby as a focus for learning was a clever device to get kids thinking about some big issues. The cubby is such a precious part of childhood – scaled to suit small bodies while keeping out big bodies; a quick shelter or hideout with or without cushions for comfort, a few teddies for tea and rock cakes; and definitely a place for children’s imagination rather than adults’. The short- and long-term educational value of this project should not be underestimated. Children developed knowledge across a range of subject areas while working in teams to construct possible solutions. One child, described by a teacher as shy and academically challenged, became more confident and outgoing as a result of the enthusiasm he felt for the project.

For me, the best part of the exhibition was the collection of journals on a table at the back of the gallery. The journals expose the complexity of the tasks undertaken by both architects and students and also the learning that took place. The design tasks stretched the students in their maths thinking as they struggled with working to scale. Aspects from their science and geography learning were incorporated as they tackled issues to do with sustainability and place. They negotiated and developed teams in order to divide the many tasks. One group learnt about their local Aboriginal culture and heritage while researching indigenous plants and foods that could be incorporated into the cubby site.

Too often the playground is neglected in school budgets. A reading of a Department of Education and Early Childhood Development playground policy last year showed the words “safe” or “safety” used forty-five times and “management” used twenty-four times, while “play(ing)” and “learn(ing)” were used just twice each. The educational potential of the playground is overlooked in preference to the learning which occurs, often in subject silos, in the classroom. This is gradually changing as school leaders encourage the adoption of student-centred learning in which students are encouraged to personalize their learning according to their interests, developing complex questions that require multidisciplinary thinking.

It is always worth asking children what they would like in their school. In 2005 hundreds of students entered the School I’d Like competition, with winning entries published in The Age (May 30) and The Sydney Morning Herald (June 4). Their ideas suggested very different environments from those being built. Likewise the Eco-Cubby project challenges architects and education departments to rethink the playground.

The Eco-Cubby initiative has worked on many levels and it is pleasing that the project will continue in 2010 with new collaborations. While not every school will achieve a built cubby in their playground, the Eco-Cubby project has been an example of the rich learning that can occur when teachers and children work with professionals to explore complex problems.

Clare Newton, of the University of Melbourne, is Chief Investigator of two Australian Research Council Linkage Projects, Smart Green Schools and Future Proofing Schools.