Portrait of Denton Corker Marshall by John Gollings.

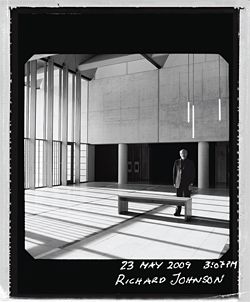

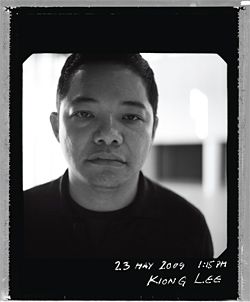

Two of six photographic portraits by Ingvar Kenne of the principals of Johnson Pilton Walker, seen in the National Portrait Gallery itself.

Kerstin Thompson Architects portrait by Luis Ferreiro.

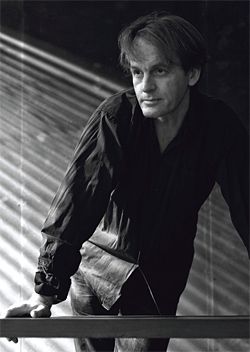

Portrait of Sean Godsell by Earl Carter.

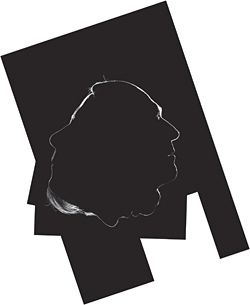

Denton Corker Marshall’s “joint head” by John Gollings.

One of several photographs of CO-AP by Ross Honeysett.

One of the series of portraits of Troppo by David Lancashire.

Troppo’s fabric canopy has been lighting-stencilled with the products of Troppo’s search for “a non-constant architecture”. The long pillow below is reminiscent of pods or leaves on the ground. Image courtesy of National Portrait Gallery.

Portrait of Gerard Reinmuth. This portrait by Brett Boardman is one of three “full-frontal” images of the directors.

CO-AP’s installation of a dozen standard white bins attempts to portray the “balancing” of art, science and humanities. Denton Corker Marshall portraits in-situ on back wall. Image courtesy of National Portrait Gallery.

Annabelle Pegrum considers the Portraits + Architecture exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery.

The exploration of identity is a central pursuit of the National Portrait Gallery. Portraits + Architecture continues this with an experimental twist as the first of a series of pictorial adventures connecting creative activity with individual and collaborative identity.

Curator Dr Christopher Chapman has set out to explore the “thinking that informs creative architecture practice”. Chapman selected seven Australian architectural practices for the exhibition and in my view he did a pretty good job. The exhibition achieves a subtle translation of creative endeavour through the self-exploration of identity by these few architects and you don’t leave wondering why them and not others.

Creative philosophies are presented without traditional drawings or architectural models and each team was invited to select a photographer to create one or more “portraits” in black-and-white A1 format. A further component is a podcast discussion with each of the teams. Recorded interviews give voice and some flavour to an essentially static exhibition but, as most architects know, you are more often judged by what you do than by what you say. In any event, not everyone who goes to the exhibition will listen to these conversations and frustratingly not all of the podcasts work all of the time.

The overall studio-like image of the exhibition is familiar to all design professionals. The layout is simple and the material provided in each display is inclusive and absorbing and tactile. There is no sense of preciousness – you want to and can rustle and riffle through the papers on show and touch the displays, if not the portraits.

Not unexpectedly, the installations make use of different techniques to describe the complex world of architecture, yet there are common and recurring themes that visitors would recognize and appreciate – intellectual adventure; teamwork; the fabric of space and context; the making of drawings, notes and models, not as illustrations but as thought in action; and the dragging of an idea into the physical world.

Some of the subjects reveal more of themselves than others. All see architecture as an intuitive act, variously described as a pervasive career, a balancing act and a roller-coaster ride. There are guarded references to how hard it all is, but many hints too at the fun and pleasure of design.

All of the works seek to engage you with the creative process. On entry visitors are encouraged to make a paper cup composition, to draw or to play before they view the “portraits” and as they leave the exhibition. This is part of the installation by CO-AP and based on the collection of remnant cup structures it’s very successful. In the same spirit students of architecture at the University of Canberra, led by lecturer Ann Cleary in collaboration with the NPG, examined the exhibition theme with reference to spatial awareness and “embodied sensibilities” and the changing compositions of light and interstitial spaces of the gallery. The students presented their work in a range of mediums as part of The Big Draw, a weekend forum where visitors to the gallery were encouraged to contribute to a series of mega drawings and markings.

There is a sense of rightness in finding the exhibit of Johnson Pilton Walker, architects of the Portrait Gallery, just inside the entry door. The building is now the recipient of a swag of design awards and the actual table on which it was conceived and detailed is central to their installation.

All see architecture as an intuitive act, variously described as a pervasive career, a balancing act and a roller-coaster ride. There are guarded references to how hard it all is, but many hints too at the fun and pleasure of design.

Images of the design team at work are screened onto the table and visitors seem to delight in laying their hands on it. On the wall behind is a run of iPods, with ever-changing pictures of those involved in the project. Creativity is presented as a collegiate event, one of humour and fun mixed with the hard slog of the work. Six photographic portraits by Ingvar Kenne show the principals of the practice at various times of the day standing within the gallery. Changing shadows in each picture pay homage to the way the architects have captured light within the building. As these are the first portraits commissioned within the building, this is a nice touch.

Kerstin Thompson introduces a humanity not obvious in some of the other presentations. With pictures full of life and colour, her spaces are portraits of the people who use them – at home with kids, at a dinner party, at the police station, where ordinary people do tough jobs in simple but good environments. Thompson most clearly decodes the enjoyment that can come from the practice of architecture, and the portraits by Luis Ferreiro depict her office searching for pleasing environments that will connect to their users and their neighbours.

The photograph of Sean Godsell by Earl Carter is closest to a portrait of the architect as artist and Renaissance man. With great simplicity Godsell has pinned to the wall a long spread of diary-like pages of diagrams, musings, correspondence and media clippings, including abuse from critics because he dared to try something new. Arranged as overlapping leaves, the documents invite you to flip through them as you might a much-loved book. In the midst of these papers there is a letter he wrote as a child saying how much he wants to be an architect like his daddy. The whole gives a sense of the passion and calling of architecture and the sheer guts that it takes to make good buildings.

With one sweeping and truly lyrical sketch and a generous pile of crushed and discarded trace paper, Denton Corker Marshall conveys the interface between concept and realization and the iterative nature of design. Asked about their collegiate approach, John Denton says in his podcast that the three directors work together in one room, giving the office the benefits of a “joint head”.

John Golling’s photographs explore this collaboration perfectly with distinctive portraits of the three – grouped at the top of a long and floating staircase, standing side by side, and backlit in a wonderful silhouette.

The portrait of CO-AP by Ross Honeysett breaks the mould with a mosaic of several A1 photographs. It is a dynamic portrait that shows the team running up a staircase and it harnesses the youth and energy of their collaboration. In his podcast Will Fung describes architecture at CO-AP as a “balancing thing” of art, science and humanities, but their installation of dozens of standard white plastic bins tied together to sculpture space does little to articulate this approach.

Troppo has the most representational installation on display, with a delicate tensile structure of materials more found than sourced. A fabric canopy has been lightly stencilled with the products of Troppo’s search for “a non-constant architecture”. Underneath is a long pillow reminiscent of pods or leaves on the ground. The photographs of David Lancashire form the backdrop to the structure, with the team placed in five different and almost ethereal landscape environments. The whole is fragile and transient yet inviting. I watched visitors mill about the construction with initial trepidation but soon relax and enjoy sitting beneath it gazing at the pictures.

At the far end of the exhibition is the installation of Terroir, the only one that includes sound. Against a dream-like film of shifting blue skies and tumbling images, the architects have a gentle dialogue/monologue about creative process, education and practice. It is an introspective film that tackles broader philosophical issues. Words rather than phrases stick with you – shock art, technique, conflict, dilemma, wonder, awareness. Brett Boardman’s full-frontal photographs place the partners against plain white panels dropped into the urban, coastal and outback landscapes within which they work. These are linked with pictures of two small and empty architectural studios full of clutter and potential. Together the portraits and film provide a powerful depiction of place and the “stuff” of design.

This exhibition is an ambitious and worthwhile undertaking by the National Portrait Gallery to profile architecture as a creative force in Australian culture and identity. Let’s hope for more in the future.

Annabelle Pegrum is a Professorial Fellow of the University of Canberra and head of the design disciplines in the Faculty of Arts and Design. For further material on the exhibition see www.portrait.gov.au/exhibit/architecture/.