Falls the Shadow is a record of the aspirations and many difficulties behind the design of the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) in Canberra, according to its original architect, the late Col Madigan, and other critical protagonists and advocates. The publication provides an up-to-date account of the status of national institutions, and of an architectural profession incapable of endorsing its own achievements and legacy.

Falls the Shadow published by Uro Media.

The NGA received the Canberra Medallion in 1982, and Madigan was awarded the RAIA Gold Medal in 1981. On a public stage such as the Parliamentary Triangle, there is simply no place to hide. The intensity of conflict as documented in Falls the Shadow is only amplified immeasurably in these circumstances. Ominously and knowingly, it raises the uncomfortable matter of transparency in public life at the very place designed to be its most lucid incarnation. The results are detrimentally ambiguous and in all likelihood irreversible.

Falls the Shadow is an attempt to address an injustice, namely the abandonment of the “great National Place” during construction of the NGA. The underlying axes and orientation of the NGA design were all determined by this urban plan. The book admittedly invokes the saturated bureaucratic undermining of Burley Griffin during his time in Canberra, as if it constitutes an infamous tradition in itself. The handling of the later extensions to the NGA, in particular, invite embittered recollections and protests at the betrayal of “open procedures” and “moral rights” for the “black letter law of contracts,”“closed-door policies” and “meaningless professional behaviour,” where a “small percentage distinguishes ignorance from excellence.”

The editor’s note in Falls the Shadow makes it clear that the book will not be neutral. [In the editor’s note to Falls the Shadow, Paul McGillick writes: “This book does not set out to be neutral. But nor does it set out to denigrate anyone. Instead, it aims to celebrate the rich complexity of one of Australia’s greatest buildings.”] The NGA’s shortcomings are portrayed as differences in curatorial philosophies.

There is also a meticulous summary of correspondences provided, which reveals a vicious divide in the architectural profession observed by a largely unimpressed and indifferent public bureaucracy. Paul Virilio wrote that “the age of artists” has been replaced by “the age of executioners”; Falls the Shadow endeavours to demonstrate an absence of exits when a cultivated micro-discursive manoeuvring succeeds. By the end of Falls the Shadow, an exasperated and reluctantly defeated Madigan writes to the then-president of the RAIA: “It seems your institute’s responsibilities [have been] abrogated. The question is what is the role or point of your office?” In another letter, Madigan encloses a report titled “Who cares?”

As the main protagonists are all identified, Falls the Shadow carefully acknowledges that it does not wish to denigrate individuals. Whether that is the case or not, too many figures and circumstances are nevertheless interchangeable. They include members of government organizations with names that defy acronyms, political expediency in all its forms, institutionalized unaccountability, and a professional equilibrium that ensures once and for all that any ideological vestiges in relation to architectural practice are largely a personal persuasion polished into the principal efficacy of the project.

There are accusations in Falls the Shadow that imagine misanthropy. Madigan and his supporters may have been ultimately exhausted by the sublime interchangeability of their adversaries. The defence of crystalline orders investing every dimension of the NGA and other allegories of baronial halls and old Hollywood in the Canberra landscape appear seemingly innocent, yet this defence is inevitably unsustainable when limited to the personal expenses of finite and irreplaceable individuals. Futility itself threatens to perish eventually with the “despairs for the characters in our profession.” Falls the Shadow is necessary in arresting that possibility.

Falls the Shadow raises the spectre of representation and national identity as extravagances from another era. They are idols belonging to the occidental monuments of the twentieth century nation state. The punctuations and professional executions of synchronized global progress do not possess a comparable or necessary singular innovation. They shine in a “dense fog of apathy.” There are conclusions in Falls the Shadow where architecture becomes a form of “confectionery,” “multiple choice design methodology,” and a “one-page dot-point synopsis” that reveal what is now delivered by the profession.

At this termination point, architecture as a soft pathos for fading grandeur is indivisible from the instrumental discipline of building production without sentiment. However, Falls the Shadow fails to reach this point. In the struggle between “wit and vitriol” and “the current climate of spin and style” there is no control of the irreconcilables that negate each other.

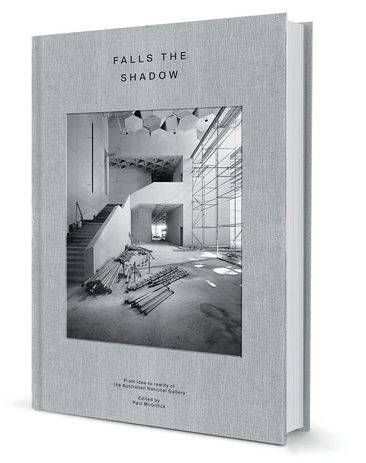

If Falls the Shadow assumes responsibility for the NGA legend, then Max Dupain’s photographs of the original edifice are prophetic in their nihilism. In these images, shadows possess a mass greater than colossal planes of cast concrete bathed in photographic exposure. The images create the legend. They are a proof of the NGA.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 14 Jan 2013

Words:

John Bralic

Images:

Estate of David Moore

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2012