The aesthetics of public space

John Macarthur

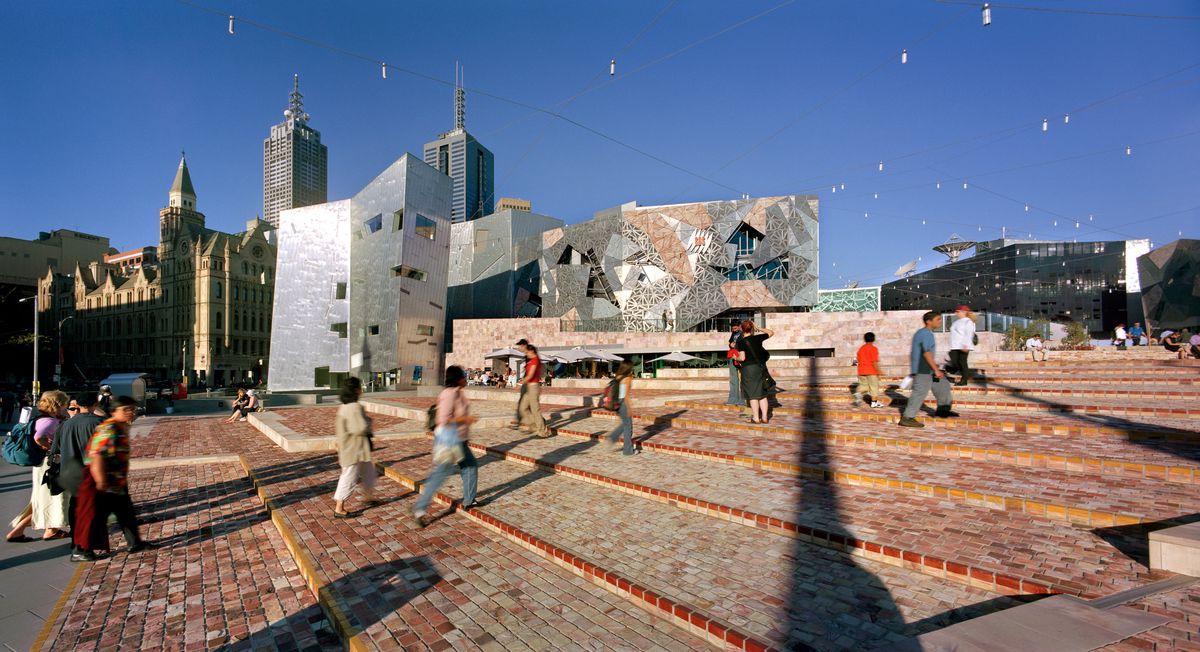

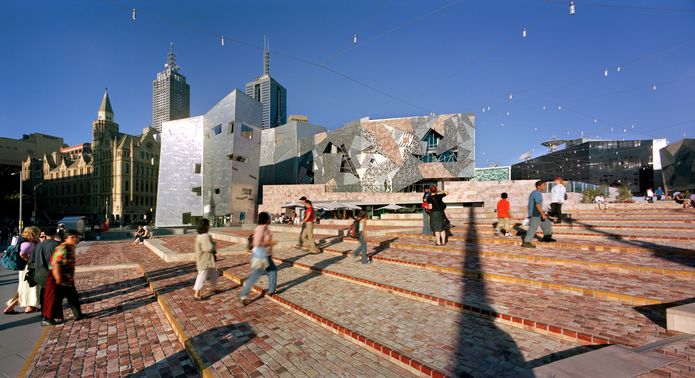

What is refreshing about Federation Square is a certain familiarity married to whole scale formal invention. It is a public building – something that many have thought obsolete or nostalgic. To be sure, the formal language and some of the spaces of Federation Square are novel, unfamiliar, and indeed illegible to the public. And yet it is exactly this novelty, and a degree of inscrutability, which, when safely bracketed either side by an intelligible programme and a notably expensive building quality, recalls the type of the public building. Since the twentieth century one of the sites at which “the public” forms itself is around the scandal of the unintelligibility of modern art and architecture. So, we might say that Federation Square combines in a pleasing manner some challenging buildings with a relation between architecture and the public that is, at a more general level, quite familiar. The people of Melbourne are, by all accounts, pleasantly shocked.

To consider the merit of Federation Square is to consider how effectively this common space of the public is tied up in the game of culture. The risk for the architects is that the novel aspects of the buildings’ form might unwind from its place and programme. Some might judge that Federation Square is an ornamental skin on a well-thought-out civic chassis, its harlequin display so thoroughly required that any kind of formal craziness would have answered. And yet, I think that Lab Architecture Studio and Bates Smart escape this censure. In its breadth, the project knits together considerations from the programmatic to the expressive, while, in its depth the project achieves an impressive tangle of the wayward trajectories of high architecture and public discourse, which is something that we are seldom shown in major public commissions.

If we turn, first, to the familiarity of Federation Square as a public building, one fact impresses architects and the public alike – its expense. In recent decades governments and architects have perhaps too quickly collapsed the difference in building quality between public projects and the “public” spaces of shopping malls. The scope for public architecture then becomes that poor and strident space of identifications of the kind that can be made by nine-year-olds. Money, on the other hand, speaks and there is an immediate authority accorded to a building with a design life of a hundred years, even if what it has to say is complicated, equivocal, and unexpected. Federation Square looks and feels expensive. While its fabric may not meet the usual expectations of craft and material, it is clearly not intended to be replaced in twenty years. Conspicuous expenditure is an important tool of government. Making expensive buildings in prominent places and opening them to the public speaks of surety in contrast to the secret expenditure, the leakage, and favouritism that is the taxpayers’ great fear.

Federation Square then meets the ancient first criterion for culture; it is a kind of exuberant sacrificial act that makes everyday life look metered and mean.

This expenditure is not simply a calculation about the cost of building, but a symbolic economy of the value of land and buildings over history. Federation Square is familiar as a public building because it under-invests in floor area and over-invests in building quality. Traditionally, public buildings were distinguished from commercial developments by being set back from the street and by having a small building volume.

Federation Square is quite like this: set back off Swanston Street, the majority of its buildings are neither higher nor deeper in plan than nineteenth century buildings. So, although I’m sure the typical experience of Federation Square is that it is big, this generosity is not only a matter of how many square metres of public facility are made available, but, paradoxically, of how few square metres of building per se are built on that very expensive site; of how much productive investment has been foregone.

Federation Square is a contextualist building in that it not only has a familiar scale, and achieves some interesting connections with its context, but it also seeks to imitate the experiential parameters of Melbourne’s nineteenth-century structure of streets and lanes. The route up and across the square from Swanston Street crosses over the Atrium and is a clear and memorable primary structure, and the complex is fractured by lane-like openings. None of these spaces is like a street or a lane, but the hierarchy is familiar. Like the traditional city block, Federation Square seems like one thing at a distance, reveals itself as an ensemble as you approach and then reveals the addresses of the various tenancies at the point when the information is required. Its structure is intelligible, but without being pedantic.

The sense of familiarity which I experienced at Federation Square includes these aspects of status and expense, site usage and scale, and urban morphology. But we must ask if this is a good thing, or, is it a constraint which the architects have failed to overcome? Perhaps cultural institutions, and their architecture, exist to exhibit wellknown traits of urbanity in the design-themed precincts that central cities have become; places where the questions are well known and the answers varied and amusing. I would say that the difficult and new questions of what the public is and what cities are lie further afield. But I don’t conclude from this that the architects were obliged to have raised these questions with this project. They have been able to anchor a project, so otherwise avant-garde, in a legible public culture of urbanity, however chimerical that culture has become. To test the project in the terms it sets itself, we need to consider just how tight it draws the wire between what I have called its familiarity, and, what is more obvious at first glance, its strange and broad inventiveness.

The architects have employed non-classical geometries that govern surfaces and three-dimensional form at a variety of scales – from the parti to the lighting grid. These geometries, which are not all the same but are genetically alike, are based on concepts of fields of force and focus. Like the process of sketching where a line appears from a series of pencil strokes, the forms of Federation Square arise from a reiteration and accumulation of actions within the system set up by the architects. The architects then recognise in this field of textures the kinds of forms that suit a particular task. The architecture lies in the judgment, reason and logic applied rigorously to this otherwise arbitrary system. This same attitude to form governs the project in plan, and elevation. This is not a simple homology of shapes. The three-dimensional form of the buildings, the facade panel system and the interior planning cohere through their difference as much as through their commonality. Like an Aeolian harp sounding in the wind, the aspects of the buildings’ form harmonise ambiently and without direction or overall structure.

For a visitor, the affect of this formal aesthetic is a kind of liberating bewilderment.

Seen against the city, Federation Square is as different and peculiar as if it came from another culture altogether, and yet there is no one thing to grasp about it. From within Federation Square, the edges blur – it doesn’t exactly bleed or merge into the city but becomes fuzzy against it. The parts, such as the facade segments or the framing of the Atrium, have a high degree of complexity and particularity, and thrust themselves in to a sharp focus. But, rather than these elements cohering into an overall object-form, Federation Square seems as if it is not a “thing” at all. The “thing” that Federation Square becomes is a visual effect forever receding; the horizon of the field of formal conditions we experience close at hand.

In these aesthetic affects (and the ingenious tectonic contrivance which actualises them) the architects of Federation Square share an aim with many progressive architects of the late twentieth century. This is to devise a language of form, but one that remains vague and indefinite. To a certain extent, this is an aim that should be understood in its negations. An indefinite formal language does not premiate inclusiveness, as did the discredited Esperanto of Modernism. But nor is it intended to be the private code of an utterly unique object as is the case with some expressionist architecture. Federation Square is system of forms, but one that has arisen on occasion. It could be repeated and expended like modernism or classicism, but it will not be. It will remain idiomatic to the site and programme. Neither does Federation Square indulge in the illusion that there is anything much to say. At a second level, these negations clearly do have an import – they stand against understanding culture as the simple-minded affirmation of the world as it is.

These issues of what form is, where it comes from, what its significance is, are not particular to architecture. However, it is not possible to understand the patient and faithful pessimism of late twentieth-century architects around this issue without understanding architecture’s recent history, and how, as a discipline, architecture understands its trajectory to be partly in common with, and partly distinct from, culture as a whole. This cannot be easily explained outside the discipline – to a public who still work with a concept of beauty, to governments that think that culture is good for forming docile populations. And yet I imagine that everyone must feel something of this timely doubt in the interval between what I’ve described as the familiar aspects of Federation Square and its startling actualisation. This gap for thinking and feeling could close quite quickly if Federation Square were novel in a trivial sense, as with futuristic buildings at World Expositions. The effect of futuristic architecture is not actually to allow us to walk into the future, but to form up the public into a body all facing the same direction. Federation Square, by tangling up the arcane discourse of late avantgarde aesthetics with the fading grand narrative of public space does something better I think. It opens a space for the public to feel that “we” might be something else.

DR JOHN MACARTHUR IS A SENIOR LECTURER IN ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND AND VISITING PROFESSOR AT RMIT UNIVERSITY.

Urbanity and federation

Graham Crist

Federation Square belongs to a tradition of civic projects where the architectural monument is enlisted in an urban recovery campaign. The treatment of the site and the healing of a few sores to create the City Beautiful was a clear agenda of the brief. Specifically, a series of actions was demanded for the site: the definition of a city edge, the uniting of the city with its river, the extension of a gateway or garden zone between the two, and the creation of a civic space which was to be both significant (meaningful) and comfortable. All this was to be achieved on a site without a ground plane and, by providing both open space and permeable buildings, was to satisfy the urbanist’s notion of “the Public” as an index of the democratic and therefore of federation. The building programme could be seen as fulfilling a primarily urbanist function – to support the square by making it lively and to make the costs viable. It is a site as dense with aspirations, and as rich in speculations over many years, as any in Australia. (The Sydney Opera House and the Federal Parliament spring to mind for comparison.) As construction nears completion, it is now possible to think of the project both as one of many urban speculations, and as a concrete bit of the city.

Edges and centres. The city, by some definitions, ends on the north side of Flinders Street. Seidler’s Shell House marks the corner of the grid at Spring Street and infers a street wall continuing along the boulevard. This edge in part became an urban design justification for removing the Gas and Fuel towers, and reinforced the attachment to an open panorama of the St Paul’s facade. The question of whether the grid plan should be taken beyond Flinders Street engaged many of the competition projects. Lab architecture studio addressed this by appealing to a finer and more labyrinthine order of lanes existing within the street grid. This augmented an interest in using non-orthogonal, fragmented, and indeterminate geometric systems as ordering devices for the site (or any other site for that matter). The strategy has given the site a structural edge – not of built form, but of orthogonality. The architects argued that this same fragmented figure is analogous to pluralistic democracy and, as such, Australia’s federation is rendered as a generalised value present throughout the western world.

Traversing the main plaza from Swanston Street for the first time, I was struck by the artificial scene of a natural, desert-like space – a hill transplanted from the Kimberly, or some equally surreal geology. The negotiation between ground levels and the trains below has resulted in a surface which reconstitutes a pre-urban topography.

Allusions to the red centre strongly parallel the Federal Parliament; maybe here the lost hill has been returned. The desert theme is powerfully reinforced by the isolated, thin planting and the catenery lights strung across the space producing a fantastically starry sky. The light wires of course echo the tram wires of Melbourne streets, and the square too triggers imagined European hill towns – complete with winding cobbled steps. What the traditional piazza form has in common with the desert, is a stark exposure to the sky.

The sun is modulated by vertical surfaces only; there is almost no concession to the roof. This is part of an urban tradition of being sunny. The lighting of the square makes it primarily a night-time space – a gesture that is vividly local, with the light bright enough to read by.

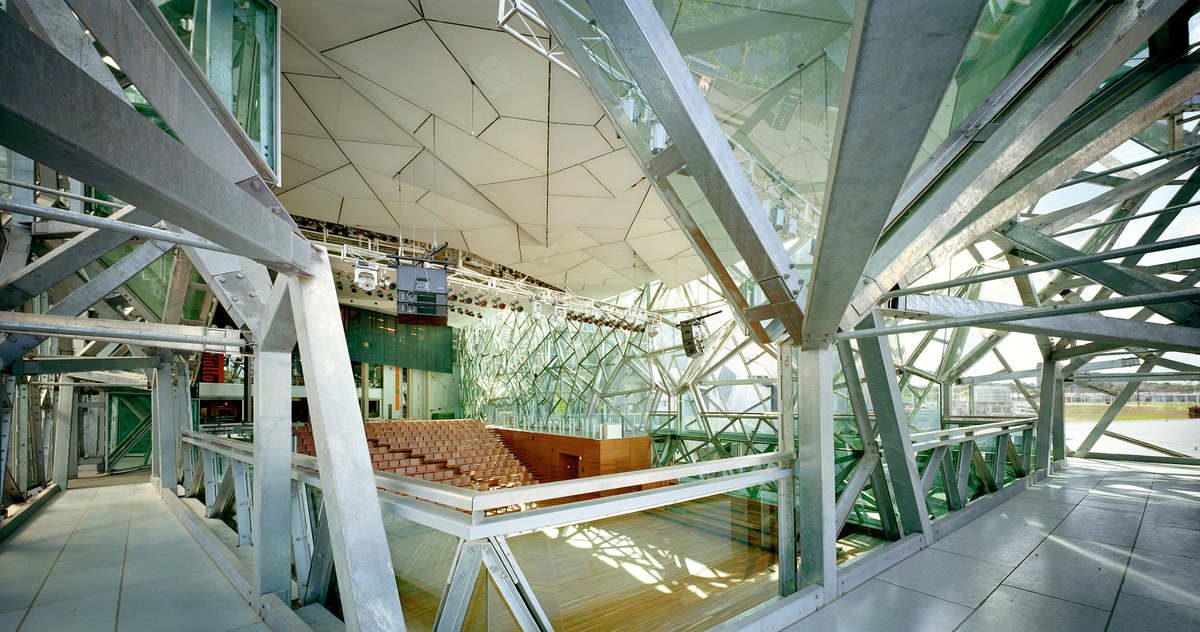

The roof does occur in the Atrium – a space transformed from the wintergarden described in the competition brief. Imagined once as a botanical glasshouse, the Atrium is a shaded street which cuts deep into the building mass. Its solid roof and chunky structure make the ground into a figure – a summer non-garden. It is tempting to see the Atrium as a foyer or a mall, just as it has been tempting to fill it with cars and Christmas trees. It is tempting also to see it as something that doesn’t yet have a proper name.

The ongoing project for Federation Square and its subsequent competition brief always held aspirations to unite its site with the Yarra River. Once divided by Batman Avenue and the broad trench of the rail lines, the promise was for the complex to extend, conceptually at least, to the riverbank. Many of the competition entries made this explicit, extending their work across a title boundary to a series of vaults and the water.

In light of this, the built outcome is disappointing, remaining incomplete in its abrupt termination at that boundary. Batman Avenue has been almost restored (minus the tram line) in asphalt, and yet the buildings do not front this street. In some places, the complex backs onto it, unsure whether there is a street; at other times it steps down to a space which is not yet there. This seems a result of political boundaries showing a hard-nosed expediency quite absent anywhere else. If only the money spent on shortening the shard had been put here.

Where the city grid and the river edge don’t meet, the architects identified a band of territory between the two – a band which is an exception, a kind of gateway and festive space, a kind of front garden. This band stretches through the new Birrarung Marr park to the sporting grounds of Olympic Park and, as an idea, it takes the place of joining the grid to the river. The botanical themes of the Federation Square brief posed the project as a garden, while the size of the programme made it a very full one. Here, the garden band is framed as an urban exception – a series of exotics. To achieve this sense of exotic species set in front of the mass of ordinary foliage, the architects have placed great faith in abstract geometry – both as a plan figure and as a surface motif.

This serves to be unlike the orthogonal and normalized forms of the CBD.

While the gestures of urban structure are made entirely as a plan gesture, the expression of the exceptional geometry occurs through the facade and ground surface.

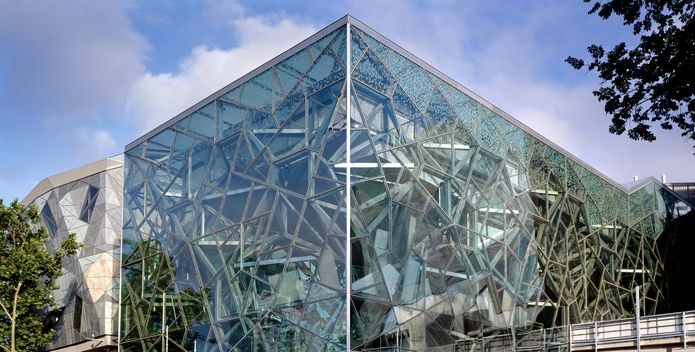

The patterning of these surfaces is exceptional. A glance back at the competition model shows just how much the facades have developed. As built, they are as rich in materials and articulation as anything ever built in Melbourne. Feats of craft are present everywhere. The pattern has been consistently applied, so that the object patterning over walls and floor has produced an effect which is “all-over” and even rather than fragmented and pluralistic. It is more like a Pollock painted surface than a series of diverse gestures knitted together.

Wherever possible ordinary building is avoided – both by substituting crafting for the ready-made and by suppressing spatial elements under abstract screens. A noteworthy moment of mere building is visible from the south-eastern approach. Here some of the facade screen stops short revealing a roof fascia and glazing, and revealing, also, just how extensively signs of built scale have been eliminated generally.

The detachment of the facade from the building skin has its own structure, and allows the patterning geometry to run freely across the forms. The spectacle for the tourists we all are, is that of staring at these screens. It is a spectacle that is already becoming a favourite, and one that is successfully scale-less and not building-like. It is one of gazing and not of reading.

Open up a few sores. Federation Square, now built, has healed some of the urban wounds of modernity. It has re-covered a ground and folded it back into the city, with a high-culture mall. The cutting short of the western shard was a mistake, the halffinished treatment of the water edge is a mistake, but these don’t overshadow generally sound urban moves. The diagram is again intact.

In contrast to the urbanist’s view that the ideal city can be diagrammed, is the position that a city is merely made of more or less compelling objects. Perhaps the traditional forms of urbanism structures and vistas become secondary when an object itself is able to wake up certain longings for the extra-urban. This is to ask for some significance – to ask what a building can do to a city, and what a city can do to us.

While we will cope with the river edge being as it is, just as countless cathedrals have survived their vistas being occluded, we might still ask for the building to add weight to the city.

The title of Federation Square seems to demand some such gravity – to at least provide a promise of significance, and in doing so, maybe even to open up a few sores – of history and of disagreement. While this building is formally sophisticated, pumped-up and festive in its programme; until something is added, these seem distractions. Perhaps the urban object and its exterior space don’t really matter – maybe Federation Square is about interiors. To mis-quote Venturi and Scott-Brown, Australians don’t need piazzas, they should be inside art galleries, or watching what comes from the SBS television studios. Melbourne has some fine new facilities, a spectacular new postcard opportunity, and can consider itself a fine international patron of architecture. Maybe that is enough.

Yet the hopes of many urban ideas seem to have been invested here. The replacement for the City Square, the replacement for the Gas and Fuel towers, Melbourne’s own Sydney Opera House, even some of the lost political space of the new Federal Parliament. Maybe that is the problem and the source of my doubts – that too much is demanded of the architecture.

Perhaps, more optimistically, we need to wait, as several others have suggested, for significance to emerge, for the events of urban life that can imbue this landscape with significance. I think of the front page of The Age, 19 May 2002, and the photograph of the thousands who worked on the building. The collective effort to make this work may be enough of a start. We wait in hope.

Post script. On 14 February, the square hosted some of the biggest demonstration crowds in Melbourne’s history, and the space worked. The process of entering significant urban life was begun.

GRAHAM CRIST IS A PARTNER IN THE PRACTICE S-ARCHITECTURE AND A LECTURER IN ARCHITECTURE AT RMIT UNIVERSITY.

Urbanity and federation

Gevork Hartoonian

ANY DISCUSSION OF the Federation Square project must involve two questions that have been on the architects’ table since the sixties. Firstly, what is the civic dimension of architecture in late capitalism, when every production activity is subject to the nihilism of technology, if not the aesthetic of commodity fetishism? Secondly, how does architecture relate to its near past, to the conventions of modern architecture in general, and the exhaustion of the tectonic of steel and glass architecture by Mies van der Rohe? This last development has left many architects to follow the architectonic implications of Robert Venturi’s idea of the decorated shed. In Australia, the absence of a parallel to the work of the New York Five architects has meant that Australian architecture in general, and Melbourne architects in particular, have chosen to maintain the idea of the decorated shed as the only way to resists the “regionalism” that prevails throughout most of the country.

This interpretation of the country’s recent architectural past offers a plausible framework for discussing Federation Square. For the past two decades, architects have struggled with the challenge posed by digital techniques: how to rethink architecture’s interiority using a technique that does not contribute to the materiality of construction, but, at the same time, offers significant perceptual vistas – equal to those initiated by the ocean liners and machines so dear to Modern architecture? How do we differentiate Lab architecture studio’s design for Federation Square from Frank Gehry’s Bilbao building, which was equally, and perhaps more forcefully, conceived under the spell of digital technologies?

The design of Federation Square does not merely lend form to the logos of digital techniques. Yet it stops short of rethinking the idea of the free facade and “thickening of the wall” beyond the architectonics of the decorated-shed. This paradoxical position is, for me, the most intriguing aspect of this project. Another important aspect of the design concerns tectonics, particularly, the reconstruction of the site as a topological extension of the city.

The overall design strategy derives its form from the given programme and the site’s position within the urban context of Melbourne. Like most successful designs for institutional buildings, Federation Square classifies the site by rejecting contextual references, and yet it projects into the site an image and form that it needs. The project takes advantage of its situation – its location at the edge of the city and its proximity to the infrastructure (Princes Bridge) – and maps a topographical landscape that does two things. Firstly, it aligns the two most significant buildings of this complex, The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia and the Atrium, with the topography of the existing city via Russell Street. Secondly, the composition of the other buildings offers a plaza to St Paul’s Cathedral, a space that would have been experienced more forcefully if the authorities had not cut the height of what is called the “Western Shard” almost to half of what was originally proposed.

The triangular geometry situating the eastern and western shards, and the “Neo- Pub” commercial building frames the undulating plateau of St Paul’s Court, and structures the regulating lines of the cladding that covers the rest of the buildings.

The architects’ approach to the cladding is problematic in that it freely moves from the tectonic of dressing, discussed by the nineteenth-century German architect Gottfried Semper, to the “dressed-up” quality implied in the idea of the decorated shed.

While the former view artistically articulates the manifold lines of a building’s body, the latter’s artistry is conceived as a composition in advance of the process of construction.

One operates like flesh covering architecture’s body, the other, looks like carnival clothes designed independently of the body’s contours.

The latter approach is clear in the cladding of the Australian Centre for the Moving Images (ACMI) and the Yarra building. Here, the space inserted between the structure of cladding and the physical enclosure of the building displays the excessiveness of the design strategy. The

cladding camouflages an enclosure that responds to the horizontal line of floors and the location of window openings. The thickening of the “wall” as a tectonic figuration has been at work since the Renaissance, as well as having been dramatized in late Corbusian architecture. In these two buildings, it operates like a mask that has nothing to do with all that is behind it. Nonetheless, on several occasions the enclosure is cut along the lines of the geometry of the cladding, providing a visual contact between interior and exterior spaces. According to the architects, the location of these openings is based on the contingencies of the interior space and its relation to the immediate site and the different vistas of the city.

The excessiveness that prevails in the ACMI is balanced by the tectonic of excess implemented in the NGV building, perhaps the most successful building in this complex.

Here, the thickening of the wall operates in manifolds: it reformulates Louis Kahn’s tectonics of served/service spaces by hiding the mechanical ducts between the surface of cladding and the main body of the building. In doing so, the polychromatic surface of the cladding – a combination of sandstone surfaces with zinc and glass – closely follows the topographical movement of different parts of the building. This strategy is most successful in the southeast facade of the ACMI building especially in the plan and section drawing that cuts through the southern stairway. The planimetric organization of the NGV is informed by the “dual filament” composition that houses the galleries. It provides a unique spatial configuration that is mostly experienced in the edges of the plan. The north and south intrafilaments are among the most intriguing elements of the NGV; a volumetric composition in which the space is dramatized by both natural and artificial lights, and a sculpted volume that houses one of the emergency stairways.

The tectonic strategy maintained in the NGV culminates in the Atrium. This building might be characterized as the architectonic realization of the nineteenthcentury architect’s dream – how to use steel and glass beyond the aesthetics of engineering and the mental trap of historicism? And yet, implied in this astonishing space is a message for architecture: any attempt to transgress the formal potential of the Cartesian coordinates falls into a void with double signification. In late capitalism, public space could only be an empty space occupied by commercial products from the culture industry. As Peter Davidson of Lab architecture studio notes, people are traumatized by empty spaces. While the void was essential to Mies, the architecture of the Atrium conjures the void with the sublime beauty of its skinned-structure, offering a plausible alternative to the sense of mourning implied in Mies’s later architecture.

But there is more to the Atrium: similar to a gnarled tree, its elegant structure rises up, twisting around and leaning on the wall of the gallery. One is reminded of the return of the nineteenth-century discourse on the tectonic of organic and mechanic, but with digital technologies. If the best buildings of that century used organic elements in ornamental forms, and domesticated the new techniques used by engineers, the Atrium dramatizes the dialogical relationship between organic/mechanic beyond the conventional distinction between ornament and structure. It does so so effectively that the building itself turns into a monumental ornament. Much like the theoreticians of the nineteenth century, the Atrium confirms that the tectonic should conjugate technique with space, endorsing an intrinsic connection between ornament and structure.

The line of thinking pursued in the designing of Federation Square raises the following question: in the wake of the present culture of spectacle, how far can one stretch the “surface” without falling into the idea of decorated-shed? Like most architecture of late capitalism this project implements an idiom that orchestrates the aesthetic of theatricalization. This is clear from the heterogeneous language used for different buildings; the tectonic poetry of the Atrium, the theatrical dressing of the NGV, and the dressed-up cladding of the other two major public buildings. Contrary to the claims made for its formal novelty and “beauty”, the design of this complex adheres to the conventions of humanism. The tactile quality of the project’s cladding recalls the renaissance analogy between wall and paper. On the other hand, if the “expressionism” maintained in both blob architecture and in the Bilbao museum represent two architectonics of the spectacle initiated by digital techniques, the problematic strategy offered in the Federation Square could be formulated in the following question: could architecture articulate a critical response to the conditions of its production without the de-subjectivization (abstraction) of its tectonic figuration?

DR GEVORK HARTOONIAN COORDINATES THE MASTERS PROGRAM IN ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY.

The art of building a building for art

ZARA STANHOPE

While celebrating long awaited arrival of several new cultural spaces in Melbourne, there is also now the opportunity to consider their functionality and value for the cultural organizations and audiences they are to serve. Do they deliver for artists, institutional curators, choreographers, designers and other stakeholders, including audiences, members and sponsors?

It is still early days for the curators at the new Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA) and at the two Federation Square spaces – The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia and Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) – who are in the process of familiarizing themselves with their spaces and determining how they will use them, and the consequences for the public. With this in mind, this review considers the curatorial opportunities and potential challenges arising from Lab + Bates Smart’s design for one of these new spaces, The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia.

The other new institution at Federation Square, AMCI, was in the unique position of being able to rationalize both physical space and organizational philosophy simultaneously. In contrast, the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), like the nearby ACCA, had the opportunity to re-evaluate existing operations with the establishment of new and enlarged spaces. The NGV’s brief to Lab + Bates Smart specified gallery spaces able to contain all forms of Australian Indigenous, colonial and contemporary art (to maximize opportunities to show the more than 22,000 paintings, works on paper, photographs, objects, design and fashion and textiles in the NGV Australian collections). The result was twenty-one distinct spaces or “galleries” totalling 6,800 metres over three floors.

The flexibility required to accommodate the public’s favourite works, as well as contemporary projects and travelling exhibitions of differing scales has been addressed by building spaces that can handle large works or be sub-divided.

Neither the drab “halls” and “courts” of the original NGV building, designed by Roy Grounds, nor the domestic scale of the previous ACCA (a converted and extended cottage) provided Melbourne audiences with the archetypal “white cube” gallery space that continues to be upheld in the visual arts as the preferred philosophical and architectural form, due to its apparent neutrality. Today this model strains to accommodate the transformations that contemporary art and museum practice have continually undergone since Modernism. Even prior to the second half of the twentieth century, the white cube had been variously coloured, perforated, deconstructed and dissolved in efforts to house new practices, to show filmic, sound and performative works and to take art beyond the built gallery space and into the public realm.

Lab + Bates Smart continue the legacy of the modernist white cube in the NGV’s architecture of the future at Federation Square, albeit with a twist. Behind the decorative exterior and foyer (with its Merzbau-like ceiling) at the centre of the ground floor, the galleries of Indigenous Art set the footprint for the non-regular alignment of the gallery spaces. This plan is repeated, in reverse, across the atrium, on the floors above. Almost parallel sets of off-centre rectangular rooms (“galleries”) are, on levels 2 and 3, interconnected by walkways that span void zones between sets of rooms. At ground level, Indigenous Art is able to make full use of this footprint by incorporating the area that above is an interior shaft between sets of galleries. Natural light from large windows to the Yarra River refreshes a highly charged and, at present, densely hung area replete with many forms of traditional and contemporary objects, interpretative videos, temporary partitions and coloured walls.

While the Indigenous Art galleries are unified into one discrete zone, Australian art on the floors above is divided across galleries that increase in scale as the visitor ascends from colonial to contemporary Australian art and design. These spaces are pierced by an increased number of entrance points that open the spaces to a “federation of forms and purposes”, stretching and perforating, but not transforming, the white cube.

NGV Australia, like the rest of Federation Square, offers its grand statements discretely – the faceted glass canopy of the Atrium, the embrace of the outdoor plaza, or the enormity of ACMI’s 100-metre-long exhibition hall veiled in darkness. To follow the architectural circulation of a figure eight through the NGV building is to be lead on a journey which conjures a ghostly architectural heritage – nostalgic aspirations to cultural enlightenment and modernist utopianism, suggested by features including the ascending scale of the galleries.

Such references blend with other signs, signalling the history of museums as it is relates to the commercial arcade and the public nature of visual consumption, as well as to the museum/gallery as temple. Such legacies are intrinsic to Lab + Bates Smart’s meld of romance and pragmatism. Walter Gropius and the Weimar Bauhaus set the precedent for bringing together the vision of a cultural institution as a crystalline cathedral and the iconic forms of international modernism that could embody asymmetrical design.1 Gropius was an advocate for architecture that responded to the way people move through the world, a principle which architecture and museology both still struggle to embrace. The angular plan of Lab + Bates Smart’s galleries and the offcentre location of entrances determine the viewer’s non-linear progress through exhibitions and constrict most sightlines to within a gallery (rather than offering perspectival views through adjoining rooms). This is an architecture that encourages the viewer to establish personal perceptual and conceptual connections with the art – reinforcing the context created within each gallery, and in some places between and across galleries and through internal windows, or beyond to the city glimpsed outside.

The productive creation of a tension between active and passive viewing slips into distraction, however, where the large rectilinear galleries are divided into partial and discrete zones. Achieved through the construction of partition walls below ceiling height, these

functional elements provide flexibility, but at the cost of appearing impermanent and the expense of refabrication with each exhibition.

Deviating from the grid, characteristic of both Modernism and Melbourne city, the crystalline patterns so prominent on the exterior of Federation Square are again employed for other internal design. Determining the distracting configuration of lighting tracks, this design also directs the placement of the temporary display walls, so that architectural design intrudes into the creation of exhibition meaning.

The architecture of The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia offers curatorial and creative opportunities as well as constraints. Symbolically, the polymorphous exterior, by not cohering into any one statement, can conceptually embrace the cultures of both pre and postcolonial peoples. The physically accessibility offered by the multiple entrances to the galleries (not assisted by the almost indistinguishable signage often placed above eye level) can be both invigorating and confusing. Curators and designers will need to consider the role of viewer orientation in the construction of meaning of exhibitions that extend through several galleries. Alternatively, the instability of narrative allows viewers to create their own frame of reference, opening a discursive audience space and encouraging viewers in the dynamic processes of research, creativity and interpretation.

The responsibility to enact dynamic exhibitions engendering investigation and imaginative engagement now lies with their curators, exhibition designers and, ultimately, viewers in Melbourne’s new galleries. If The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia does not, like the majority of new gallery and museum building, deviate greatly from modernist twentieth-century precedents, perhaps Melbourne has received the building its constituents, stakeholders and institution expected. More to the point, is this architecture able to accommodate the changes burgeoning in audience expectations, museum philosophies and stakeholder demands?

The flexible spaces, the incorporation of sensitively sited and informative multimedia displays and emphasis on physical access and services at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia is evidence that the issue of changing practice has been addressed in some areas. Ultimately, the effectiveness of the building will rely substantially on institutional philosophy and curated outcomes – the possibilities of which span from presentations of scholarly research to spectacular displays and exhibitions as theatre, and projects that act as a “laboratory”, think tank or forum – incorporating the architecture. Communities of users have seen cathedrals and temples be replaced by commercial and entertainment complexes and now have high expectations of seeing their culture, and its meanings, activated at Federation Square.

1. Walter Gropius, The New Architecture and the Bauhaus, p.82.

ZARA STANHOPE IS SENIOR CURATOR AT HEIDE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, MELBOURNE, AND WAS INAUGURAL DIRECTOR OF THE ADAM ART GALLERY AT VICTORIA UNIVERSITY OF WELLINGTON, NEW ZEALAND.

PROJECT CREDITS

COMPETITION STAGE 1

December 1996 – February 1997, London, UK.

Architects Lab architecture studio—Donald L. Bates, Peter Davidson and Atillio Terragni; project team—with David Racz, Shibboleth Schecter, Marco Longatti, Alvaro Conti, Miki Ando. Structural engineers Hyder Consulting— Stephen Neal + Adrian Boult. Environmental Engineers atelier ten—Patrick Bellew. Photographer Marq Bailey.

COMPETITION STAGE 2

March 1997 – June 1997, London, UK

Architects Lab architecture studio—Donald L. Bates, Peter Davidson, Atillio Terragni in association with Bates Smart, Melbourne; project team—David Racz, Jonas Lundberg, Andrew Yau, Sofia Anapolitis, James Murray, Tim Hurburgh, Chuchat Koosongdham, James Sandwith, Anthony Boulange, Eva Castro, Alessandra Papiri, Yasuhiro Santo, James Lowe, Laurenz Brüning, Shibboleth Schecter, Miki Ando. Structural engineers Hyder Consulting—Stephen Neal + Adrian Boult. Structural engineers atelier one— Neil Thomas, Aran Chadwick, Michael Mullan. Environmental Engineers atelier ten—Patrick Bellew. Quantity surveyors Davis Langdon & Everest—Paul Morrell and Nick Langdon. Models DNA—David Racz and Niahm Billings, with Architectural Models/Alan Chandler (Melb.) and Lab. Photographer Marq Bailey.

COMPETITION STAGE 3 DESIGN, DOCUMENTATION, CONSTRUCTION STAGE 3

July, 1997 – ongoing, Melbourne

Architects Lab + Bates Smart—Donald L. Bates, Peter Davidson, Robert Bruce, Roger Poole, Jim Milledge; project director—Tony Allen; team/design leaders—Fulvio Facci, Peter Bickle, Attilio Terragni, Greg Bray, Roger Chapman, Stephen Davies, Doug Dickson, Gaynor Fox, Andrew Francis, Nicole Hardman, Derek Hawkes, Tim Hill, Dylan Ingleton, Steven Javens, Olda Kurdiovsky, John McNabb, James Murray, Edward (Ted) Sanderson, David Shultis, Peter Stevens, Bill Tucker, Paul von Chrismar; project team—Ben Albury, Helen Aldrich, Kate

Allen, Lucy Allen, Sofia Anapliotis, Tony Antoniou, Jeff Arnold, Paul Bayley, Diego Bekinschtein, Leo Belci, Joanna Best, Estelle Bialek, Elly Bloom, Chantal Boisgontier, Philip Bowen, Rachel Breen, Richard Brenchley, David Bullpit, Annie Bunting, Deborah Burdett, Nina Burdett, David Burrows, Mike Buttery, Hamish Cant, Susie Calill, Raymond Cheung, Bo Christensen, Vincent Choi, Gianni Cito, Stuart Clark, Grant Cook, Geoff Cosier, Veryan Curnow, Paul Davies, Rebecca Davis, Lance Decker, Alf Dennemoser, Mardi Doherty, Craig Douglas, Dierijk Drent, Andrew Drummond, Loredana Ducco, Jan Eastwood, Colin Edwards, Ron Elton-Baker, Nancy Everingham, Daniel Flood, Mat Foley, Warren Foster, Ronald Freiverts, Jack Fullerton, Lorenzo Galati, Eleni Gogos, Stuart Grandin, Olivia Griffith, Robert Gvildys, Kathie Hall, Arthur Hallinan, Stephen Hamilton, Prani Hodges, Sean Hogan, Brett Holmberg, Olivia Hrvojevic, Lewis Hunt, George Jockov, Peter Johns, Yiu Chuen Kan, Terry Kelly, Daniel Khong, Richard King, Lucy Knox-Knight, Barbara Kurdiovsky, Vicky Lam, Ashley Lane, Libby Langlands, Anne Lau, Elizabeth Laurie, Alex Lawlor, Rachael Lynch, Roxane Ludbrook-Ingleton, William McCorkell, Andrew Maher, Gus Mamar, Luca Mangione, Nicole Mandile, Esther Mavrokokki, Kylie Meacham, Amelia Minty, Rosalea Monacella, Cassandra Montgomery, James Mulvany, Dominique Ng, Johnny O’Hara, Luciano Palma, Irene Papadimitriou, Adrian Parr, Andrew Partos, Peter Parry-Fielder, Stuart Paterson, Alex Peck, Sam Penfold, James Phelan, Toby Pond, Chris Price, Mathan Ratinam, Bhaven Raval, Stephanie Reiger, Jacqueline Ronalds, Robert Rudic, Chris Sawyer, Bianca Scaifek, James Service, Andrew Shaw, Jeremy Sheldon, Andrew Simpson, Daine Singer, Noel Smith, Thomas Sloan, Robert-Stuart Smith, Valery Sverdlin, Waihan Tang, Simon Tiller, Blythe Toll, Mike Tollis, Quan Tran, Harold Trappe, Jim Tsoukatos, Ross Weeks, Jeromy Wells, Simon Whibley, Kristen White, Stephen Williamson, Andrew Wilson, Daniel Wolkenberg, Tom Yiantos, Jenny Yim, Casimir Zdanius. Landscape architects Karres en Brands—Bart Brands, Gianni Cito, Marie-Laure Hoedemakers, Rene van der Velde, Thierry Kandjee. Civil/structural engineers Hyder Consulting—Pat Strickland, Stu Jones, Ken McLeod. Structural/ facade engineers atelier one—Neil Thomas, Dirk Zimmermann, Carolina Bartram, Scobie Alvis, Wayne Sanderson, Anil Hira, Andy Watts, Aran Chadwick. Structural engineers Bonacci Group—Stephen Payne, Roger Sykes. Environmental engineers atelier ten— Patrick Bellew, Tim Elgood. Services engineers AHW Consulting Engineers—David Worland, Roger Arnall, Hugh van Essen. Fire engineers ARUP—David Barber. Signage and graphics Tomato—John Warwicker. Specialist lighting Lighting Design Partnership—Andre Tammes, Dhruvajyoti Ghose, Frederika Perey. Acoustic engineers Marshall Day Acoustics—Peter Fernside, Peter Holmes.

Project delivery, 1996 – 2000 (on behalf of the State of Victoria, and the City of Melbourne) Office of Major Projects—Dick Roennfeldt, Damien Bonnice – project director, Tjip Faber, Isabelle Johnstone. Project delivery, 2000 – present Federation Square Management—Peter Seamer, Stan Liacos, Emma Moore. Building surveyors Thomas Nicholas—Bruce Thomas, Con Nicholas. Quantity surveyors WT Partnership—Laurie Thomas, William Kennedy-Cooke, Phil Martin, Paul Huckin. Programmer Tracey Brunstrom + Hammond—Grant O’Donnell, David Goodman, Jiong Xhu. Project managers CCS—Colin Stuckey, David Fulton, David O’Connell, Peter Axup, Phil Flynn. Public art curator Vanessa Walker. Artists Paul Carter, Christopher Bell, Joyce Hinterding, David Haines, Scott Horscroft, Carl Priestly, Jon McCormack.

Source

Project

Published online: 1 Mar 2003

Words:

John Macarthur,

Graham Crist,

Gevork Hartoonian,

Zara Stanhope

Images:

John Gollings

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2003