This is a belated review of a show that opened in Venice, in late August 2012, as an official collateral event (one of eighteen) of the Venice Architecture Biennale. I had been at the opening of the Australian Pavilion the day before, where I was surprised that there was no mention of it in the official addresses and presentations. Many of the people I asked also didn’t know of this “other” Australian event taking place very close to the centre of the biennale, on a frequented route near the Arsenale. Yet there it was listed in the official biennale program and indicated on all the maps and, as those who have been to a biennale know, those maps become critical to ensure that you don’t miss anything, and everyone is looking for the scoop on and off the beaten track.

Kevin O’Brien got Finding Country to Venice assisted by a myriad of small donations and various benefactors. The project also received encouragement from the Queensland Chapter of the Australian Institute of Architects. His achievement should be celebrated, for to gain acceptance from the curator of the biennale you must pass a far more stringent international process than for selection for national pavilion representation. That one of “ours” did this should have had us singing from the rooftops. O’Brien and a colleague had proposed the project of Finding Country previously and had won the competition to be creative directors of the Australian Pavilion in 2008. Unfortunately, this exhibition did not go ahead. In late June of 2013, O’Brien won the Karl Langer Award for Urban Design from the Queensland Chapter for the Finding Country show in Venice. The exhibition also won a National Award for International Architecture in the 2013 National Awards. The promotional text accompanying his awards entry outlined the fraught journey of Finding Country since 2006.

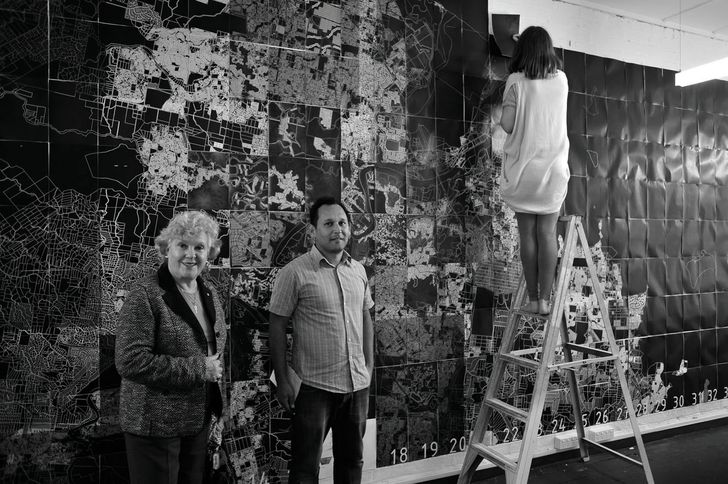

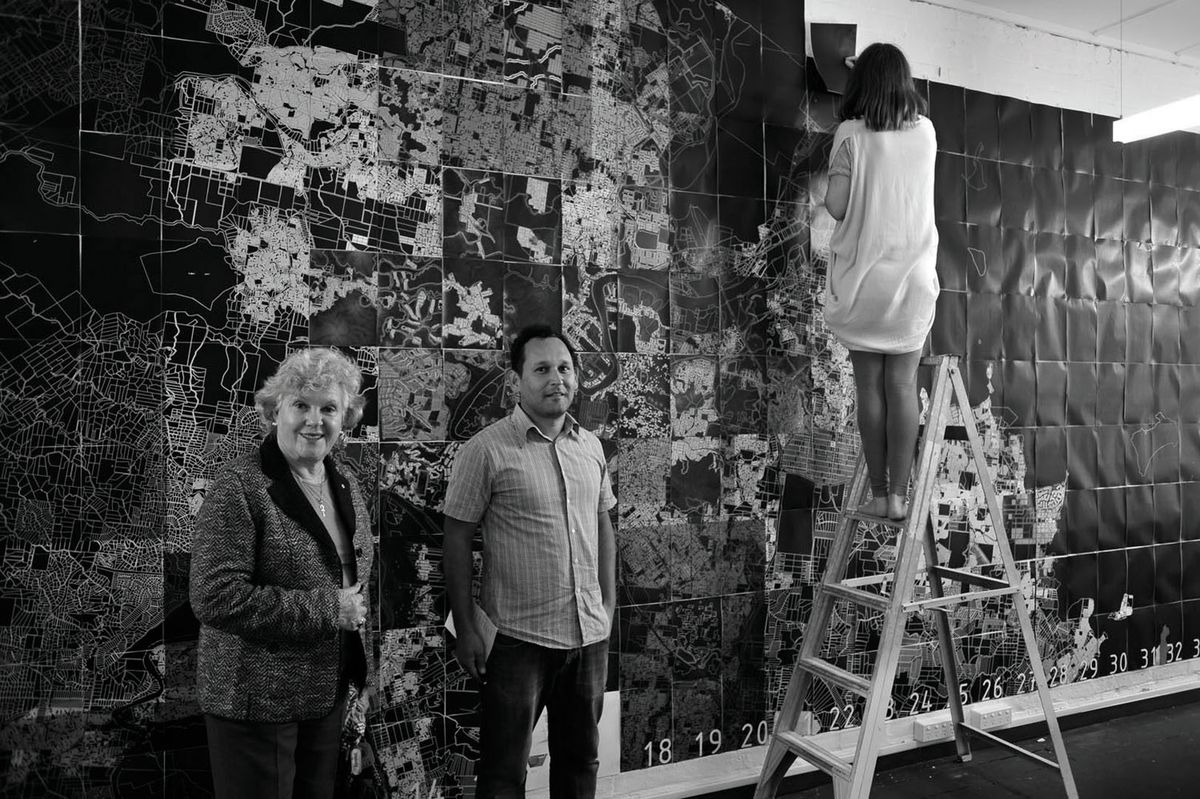

Back to August 2012 in Venice. Kevin O’Brien’s Finding Country had invited fifty designers and architects to take a piece of the Brisbane city grid and remove 50 percent of the built environment. This attempt by O’Brien via a speculative exercise to extract something that has been lost – the pre-existing Aboriginal presence – is the antithesis of the pre-Mabo terra nullius. To O’Brien’s credit he included all respondents, by his own admission some very ordinary and others great at finding or discovering special places. They were mapped on a large canvas many metres long, wedged on an angle between the floor and ceiling into one side of the gallery. (A two-room, not-for-profit space of Spiazzi, which is an artist collective in Venice.) The gallery is strategically squeezed between a canal and the end of a typical Venetian footbridge for maximum exposure to all who pass.

The speculation certainly was mixed. O’Brien explained that the fifty were briefed for an hour, then the submissions arrived four months later. He criticized several for having missed the point, for erasing 50 percent of their selected area and “redesigning” a utopian ideal, in fact transforming 100 percent of the piece of the grid.

The submissions were mapped on a floor-to-ceiling canvas.

Image: David Hanson

The beauty of O’Brien’s idea is that he is not making an effort to turn back the clock but is engaged in a palimpsest to erase a certain part of the text of the city to reveal a presence that had been covered over and ignored. The well-worn parchment had indeed been abused; however, traces (placenames for example) had been left.

On another wall were five photographs. Some were of huge projections of historical Aboriginal presence onto various Brisbane landmarks, identifying powerful images (sometimes traffic stopping) of pivotal events and important figures. One of the photos is of a “Queenslander” house, which are often built of timber from first-growth forests, forests where many people had been buried whose spirits remained in the wood of those houses (for O’Brien at times chilling, at other times comforting).

The violent imposition of colonial planning principles, in a large part, assumed a blank canvas. In O’Brien’s reading, there is the possibility of coexistence, not necessarily in harmony but in contest to embody the future. In so doing he is not seeking to expand at the periphery but to return to the centre metaphorically and physically, uncovering what cannot be seen, and rediscovering links to country.

The palimpsest parchment analogy can be advanced further here, projecting sustainability, recognizing and recycling the parchment (read land) as the ongoing social and cultural resource of country. Country that has always been there, waiting to be uncovered, accumulating richness and permitting appreciation of the fact.

The process of clearing the 50 percent is the intriguing part of the exercise. What to retain and what to erase or how that may happen is most certainly subjective. Equally the prospect of destroying architecture and not replacing it has proved an anathema to many architects.

This clearance is achieved by fire, burning as land husbandry engendering renewal and fresh growth in the Aboriginal tradition. O’Brien recounts in the exhibition his bewilderment as a young, Western, private-school-educated boy when his uncle set fire to a small island. At the time he was horrified, only much later understanding the poetic nature of his uncle’s actions and the need for and purpose of fire – for erasure and for the future of the island.

The opening of the show was a delight – a barge of local jazz musicians moored itself to the room, the singer sang in a Venetian dialect as a welcome to Kevin O’Brien, the crowd hung over the balustrade of the footbridge, neighbours lent out of their windows to see what was going on and others sat on steps or stood three deep on the other side of the narrow canal, all appreciating the music and the depth of feeling.

Even O’Brien absented himself from the gallery and stood with the crowd on the other side of the canal to appreciate the scene. The hot Venetian summer sun poured down.

O’Brien returned to the gallery and increased the heat, contrary to local regulations. Improvising a flamethrower with a lighter and a can of WD-40, he proceeded to burn the map in an act of symbolic renewal and as a statement of positive intent. All seemed to be revelling in the spirit of openness and intellectual freshness that Kevin O’Brien’s project has brought to the Australian city and to the Venice Biennale for the architects of the world.

Tate director Nicholas Serota and French architect and academic Odile Decq concurred with my thoughts that it was a shame that this spirit was lacking from the international Giardini offerings, which indeed could have done with a bit of burning to reveal what they have been missing.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 28 Oct 2013

Words:

Robert Grace

Images:

David Hanson,

Francesco Calzolaio

Issue

Architecture Australia, November 2013