NOW

There’s a bit of a ragbag aspect to my photography. It’s meant to look quick and easy – but I don’t want rough and ready. Good craft is essential but curiosity and pushing boundaries can include failure, a state of being that energizes me but haunts some of my work. I can be sanguine about the odd dodgy image as long as I have learnt from it.

Early in my student days I was shown a famous Irving Penn image – Still life with watermelon, New York 1947 – shot on 10”x8” film with that exquisite quality that only large analog images can have. The revelation was the house fly that landed on the lemon during the exposure of that frame. This was the image Penn sent to Vogue, his acute comment on obsessive perfection highlighted by the choice of the imperfect photo or the use of overripe or overlooked subject matter. This combination of consummate technician with the instinctive and experimental artist who deliberately undermined the orthodoxy of professional practice by emphasizing mortality, decay, spontaneity and improvisation has been formative to my work. It suited my personality to question technique, subject matter, meaning and pomposity, whether it be fashion, advertising or architecture.

As a result I’m more satisfied with grand failure than with complacent success. Photography has the ability to seize the moment and I relish this quality, the hand–eye coordination of watching a story unfold in the viewfinder, the narrative and implications building to a climax that you might be able to freeze. Implicit in this way of working is that not everything in the shot is controlled or organized. The anal obsession with order and detail is lost, compensated by a sense of reality and credibility that comes from this imperfection.

Thus, if the content seems irreverent or unresolved, I am at pains to have the composition so tightly controlled and consistent that the viewer is forced to assume that it is deliberate and not some random coincidence. With that confidence the image then invites criticism and reflection, of the contents and of the photographer. It is this invitation to comment that is so energizing. A memorable image has at its core two necessary components, a simple graphic and a complex argument. The absolute vitality of an idea, an attitude or a design offered to a viewer for appraisal.

For a long time now my interest has been trying to document, explain and interpret the design of cities, the buildings within them and their inhabitation. This unnatural

product of collective human endeavour is a rich subject, whose analysis is vital to progress and future sustainability. It is the technology, the physicality and the embodied philosophy that can be examined through a photograph and that challenge has been sufficient for me.

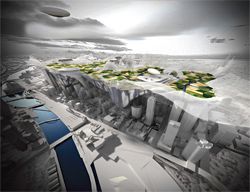

Which is a long introduction to my work for this year’s Venice Biennale of Architecture. Making these images challenged me and taught me a few lessons about tenacity and cooperation. Ivan Rijavec, my co-creative director of the biennale, and I decided to examine the current state of Australian cities, the Now, as we called it, and propose some future alternatives, the When. These are to be shown in Venice in two theatres, projected in 3D stereo. For quick understanding, imagine the Avatar of urban design.

Three-dimensional images have long been known to photographers but realistic digital presentation is only now a reality, in its infancy. My career has always explored new technology as soon as possible, which is commercially stupid but creatively exciting and challenging. Shooting in stereo nearly brought me undone but the lessons and solutions are worth outlining because every photographer is going to have to learn them as the world’s media travels inexorably to stereo output.

Modern living cities are best understood by looking at them at night from a helicopter. Scale, density, organizational systems and communication lines are diagrammed at night from the glow of city lights and are readily understood and interpreted as a consequence. So I felt the need to work at night. This has been technically difficult in the past; fast film and small camera systems made occasional usable images, but mostly they were a dark or blurred mess. Newer digital bodies helped but I needed stereo as well, which meant two simultaneous images representing the left and right eyes, both sharp and identically exposed.

Traditional stereo photography requires two lenses set 65 mm apart to simulate the human eye. Thus, due to parallax, each image is slightly offset. Looking through a nineteenth-century stereoscope, the viewer experiences a sense of depth from foreground to background. The eye has recombined the offset images, giving a heightened illusion of the depth we normally perceive but take for granted. Objects seem to be three-dimensional, as if we are looking around them, and the foreground objects can appear to hover forward of the picture plane. The effect can be exaggerated by moving the lenses apart and this has been explored by landscape photographers to get separation from distant objects.

When I wrote the proposal for Venice I made some BIG assumptions, having never actually made an aerial stereo photograph. I had read a fair bit and also shot 3D panoramas for the Place-Hampi exhibition in the Immigration Museum. This camera had 65 mm separation but very wide angle lenses and I could compose with a lot of foreground objects to heighten the depth. I “guesstimated” the design of a stereo rig with 300 mm separation and commissioned its construction.

I assumed that my existing equipment, a matched pair of Nikon D3s, would enable a night exposure from a helicopter.

I discovered that I didn’t know how to assemble a stereo image for projection, let alone run a slide show, or what sort of files were needed to get a left and right screen image onto a left and right screen projector. Then it turned out that there was a third-generation projection system called “phase shift” that was neither polarized, with its attendant screen problems, nor used active shutter glasses, which have to be synced to the projector. Phase shift has four times more resolution and is four times brighter and works on plain white walls. It is also four times more expensive but we have gone with it, after some creative budgeting. It’s been used for the last few months in Melbourne to test and rehearse the Venice presentation.

I now needed help and it came in the form of a friend, Paul Bourke from the University of Western Australia, who is the world’s expert on stereo projection. After a number of emails, and Paul handling my dumb questions, I was gradually led along the stereo path to the point where I could assemble a pair of pictures in Photoshop and would then email them to Perth, where Paul would use his own stereo projection system to evaluate my results and give me some feedback. This process was fairly depressing as I kept getting word that I did not have enough stereo separation and the effect was less than fantastic.

I went back to Laurie Rogers of the Camera Clinic – Laurie is one of Melbourne’s great institutions, along with his son Wayne – and we decided that I needed to increase separation. They built a second rig with a one-metre gap between the two cameras and a synchronized and electronic release. One of many problems to solve was that of frame numbering. I was exposing about 1,000 pairs of images on any one helicopter trip and if the electronic release didn’t fire both cameras simultaneously, then the frame numbers got out of synchronization and there was no way to pick pairs. There were some hair-tearing nights back in the studio trying to sort some of these messed-up helicopter shoots.

At this stage I was burning up a lot of helicopter fuel. I was also having arguments with air traffic control, who wanted to move me up to 2,000 feet whenever the light got good, what they call last light and I call “just perfect”. Being further away from the subject matter made getting stereo separation even harder and as the light went down the exposures were becoming very long and many of the pictures were blurred. Not only that, it was quite difficult and dangerous holding a one-metre-wide aluminium bar with two cameras at each end out in the slipstream of the helicopter. The results were still not good enough and I was getting desperate.

Suddenly there came two radical breakthroughs. Nikon released a new body called the D3S, which had a vastly improved chip and allowed exposures up to 100,000 ISO, which they rushed through to me from Japan. Then in the next morning’s email Paul Bourke recalled a formula which required my cameras to have a separation of 1/30 of the distance from a helicopter to the subject. Flying in the middle of the night at 2,000 feet would require my cameras to be separated by 66 feet.

decided to dump the dual camera system, which was giving useless results anyway, and switch to a single camera and fly from point A to point B taking consecutive images.

Even this system is almost impossible to achieve. The two images must be exactly parallel but offset. This requires that the camera points exactly at right angles to the skids on the helicopter and stays in that position until the next image is made. The trouble is that helicopters fishtail as they move through the air, and if they have a crosswind the two images won’t be offset in exactly parallel directions. So you can only fly on a perfectly still day and the pilot has to work with the GPS, which will give him ground speed rather than air speed.

calculated that if the helicopter flew at 30 km/h, then the camera was moving at 27.5 ft/s, and that if I took a picture every two-and-a-quarter seconds I would be very close to the required 66 feet. Using an intervalometer on the camera I decided to take four frames per second for three seconds. With these twelve frames I might be able to find two or three suitable combinations, allowing for helicopter vibration and fishtailing.

I rigged up my third system, a simple bar with a tripod head which fitted across the open door of the helicopter, and took off once again to test this new system – the new faster camera.

I stayed up all night scrolling through proof sheets, looking for combinations that seemed to have the correct offset and to fit together. At this stage I still didn’t know how to correctly align the pictures for a digital projection system, so I just emailed some small JPEGs across to Perth where Paul would put them together and report back to me. Finally the message came back that the results were just amazing and that we finally had a system that worked, notwithstanding the physical difficulties of getting good images during these trying night-time helicopter trips.

Among other smaller tribulations is the fact that I discovered the zoom lenses don’t work when making stereo images. I had to go back to the camera cupboard and dig up all the fast prime lenses that I owned. Needless to say there were better ones on the market, a situation that can only be solved by throwing money at the problem.

By now I was ready to shoot the outback of Western Australia. Some of the world’s biggest mining holes represent the “uncity”, an illustration of the impossibility of large populations living in the Australian desert. It’s not easy to get permission to fly a helicopter through an open-cut mine, let alone convince the pilot that he wants to do it; this much we pulled off after explaining the complex GPS flying that the pilot had to perform. Again, though, I outsmarted myself. Using “magic arms” I thoroughly tightened down the camera rig to the frame of the helicopter. This worked because we were shooting in daytime and had very fast shutter speeds but I was already aware that it introduced massive vibrations to the system from the engines and the rotor blades and that further night photography was looking increasingly problematic.

Passing through Perth on the way home, I spent three days working with Paul Bourke in his 3D lab at the University of Western Australia. This is where I really came up to speed. I was given an intensive education in 3D imaging, projection systems, file handling and developing a work flow in Photoshop for assembling the left and right pairs of images with the correct offset and understanding of the screen-depth relationships which prevent the images getting gimmicky. I had the Melbourne experimental data with me on a hard drive and all the raw files from the mining images I had just made. With my new knowledge and increasing confidence I spent the time putting new stereo pairs together, and was able to review them instantly on a screen at the university. After nearly four months of panic and heartache, this was the first time I could see some progress had been made and could anticipate an exciting biennale.

Back in Melbourne on a glorious summer night, I set out to do the final photography of that city. Vibration wrecked the images since I was still having to work about 1/30 of a second. As the rig got more professional looking, the results got worse. That night when we landed I had a fluke of good luck. In the hangar I met a chap called Reg Metcalf. He happened to be an expert in stabilization rigs for helicopters and was on secondment from the BBC. He understood the problem and promised to fix it. Using contacts in California, Reg shortly after presented me with the very latest Tyler mount, twin gyros with a stabilized pod that can be hand-held and gives me vibration-free images down to 1/20 of a second. It needs a delicate touch but when left alone it overcomes the fishtailing in the helicopter.

My pilot, Mitch Vernon, knows the Melbourne angles backwards. With our newest rig and another good night we completed the Melbourne shoot. We hardly needed an intercom; Mitch flew the flight paths we had tried many times in the past and he knows enough about photography and my lens angles that he can anticipate the compositions.

For presentation we are using Mac minis and taking advantage of their dual video output. Remarkably, the Macs will take a final image 3840 pixels by 1200 pixels and split the output left and right to the two projectors. We are coding the computers to automatically boot into the presentation software and run the slide show in Venice in a loop. We plan to leave the computers on for three months, constantly outputting the slide show so that only the projectors have to be turned on and off each day.

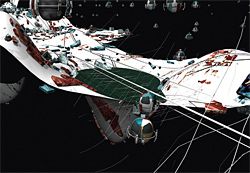

The WHEN component of the exhibition is going to be rendered on a computer using stereo output. The knowledge and experience gained from the helicopter photography has proved incredibly handy when plotting and seeing 3D cameras in Studio Max. We are able to use the same separations that we know work in a helicopter and apply the 1/30 rule to other images of the futuristic cities that we are rendering. Also, the dual camera rigs that I had initially built for the helicopters turn out to be perfect for doing ground-level architectural photographs.

When images are digitally projected in stereo the results are so compelling that I am convinced that all architectural illustration in the future will be presented in 3D stereo. It thrills me to know that Australia is now in the forefront of this technology. Daniel Flood and Sam Slicer, the rendering gurus who work out of our collaborative studio, have been remarkably supportive of this whole project. They have followed the progress of the photography and applied the lessons to their own stereo imaging. At least they don’t have to worry about falling out of a helicopter!

Teamwork has been vital in putting this biennale together. To Shahana and Sophie at the Institute, to Ivan Rijavec, to the whole team in the St Kilda studio: David Pidgeon, Sabrina Munafo, Sue Shanahan, Kirstin Gollings, Olivia Lyon and all the other staff, I give my heartfelt thanks and admiration for your invaluable contributions.

John Gollings is Creative Director, with Ivan Rijavec, of Now + When for the Australian Pavilion at the 12th Venice Architecture Biennale.

WHEN

John Gollings and Ivan Rijavec, Creative Directors of Now + When, the exhibition for the Australian Pavilion at the 12th Venice Architecture Biennale, have selected seventeen proposals for the When section of the exhibition, from a shortlist of twenty-four. (There were 129 entries in the initial competition.) Projects will be presented in the exhibition catalogue, with many also shown through stereoscopic images in the pavilion.

Ivan Rijavec comments, “In what promises to be the urban century, the design and planning of our cities is fundamental to our prosperity and survival. The overarching message of the Venice Biennale exhibition is that Australian identity has gone ‘walkabout’, it has come out of the bush and bedded down in our urban centres. Though outback and bush myths remain seminal to our culture, there is no doubt that the Australian collective consciousness is now urban.”

Island Proposition 2100

(IP2100)

Scott Lloyd, Aaron Roberts (Room 11) and Katrina Stoll.

Embodying hyper-connectivity, the IP2100 spine contains a looped system of hybrid infrastructures, initiating a new symbiotic relationship between the urban centres and their supporting territories.

Implementing the Rhetoric

Harrison and White with Nano Langenheim—Marcus White, Stuart Harrison and Nano Langenheim.

Optimistically imagines that by 2050 politicians and planning authorities will have the power, conviction and know-how to decisively address critical urban issues. Using defragmented design techniques we visualize a literal, undiluted sustainable urbanism – solar amenity, strategic density increase and walkable cities.

Loop-Pool / Saturation City

McGauran Giannini Soon, Bild + Dyskors and Material Thinking—Eli Giannini, Jocelyn Chiew, Catherine Ranger, Ben Milbourne, Edmund Carter and Paul Carter.

A manufactured crisis – a 20-metre rise in sea level – enables an exploration of the future of Australian urbanism through four distinct typologies.

Aquatown

NHArchitecture with Andrew Mackenzie.

As water and resources diminish the need for a new kind of infrastructure increases, bringing new urban forms with it. Australia’s growth cities respond like tree roots searching for nourishment, spreading into new borders and territories.

Survival vs. Resilience

BKK Architects, Village Well, Charter Keck Cramer, Daniel Piker— Tim Black, Julian Kosloff, Simon Knott, George Huon, Julian Faelli, Madeleine Beech, Jane Caught and Steffan Heath, colloborating with Village Well, Charter Keck Cramer, Daniel Piker.

From an assumption that cities have to be planned before they are formed, this project explores the conventional wisdom of the multicentred city.

Terra Form Australis

Hassell, Holopoint and The Environment Institute—Tim Horton, Tony Grist, Prof Mike Young, Ben Kilsby, Sharon Mackay, Susie Nicolai and Mike Mouritz.

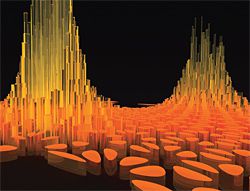

Asks what strategic moves Australia would have to make to accommodate a population of 50 million people in the year 2100.

A Tale of Two Cities

Billard Leece Partnership.

Excess consumption has bankrupted cradle-to-grave industrial economies and cities have contracted, condensed and multiplied. Visible as a holographic projection, the city’s doppelganger audits and guides the city’s development far below.

Symbiotic City

Steve Whitford (University of Melbourne) and James Brearley (BAU Brearley Architects and Urbanists, Adjunct Professor RMIT).

Layered networks of urban and rural systems allow nature and the city to combine in a symbiotic relationship of mutual benefit.

The Fear Free City

Justyna Karakiewicz, Tom Kvan and Steve Hatzellis.

Seven desperate dreams are followed by seven desiring dreams in a project that attempts to flush away fear and reveal the opportunities for a rewarding, sustainable city.

Mould City

Colony Collective— Madeleine Beech, Jono Brener, Nicola Dovey, Peter Raisbeck and Simon Wollan.

An urban system that reconfigures the relationship between humans, shelter and collective settlements. Mould will not save us, but if we learn how to tend it, new and rich possibilities will emerge.

Sydney 2050: Fraying Ground

RAG Urbanism—Richard Goodwin (Richard Goodwin Art/Architecture), Andrew Benjamin, Gerard Reinmuth (Terroir).

Urban strategies of fraying, knotting and parasitism are realized through a process of remapping and drawing across all scales.

-41+41

Peck Dunin Simpson Architects—Fiona Dunin, Alex Peck and Andrew Simpson in association with Martina Johnson, Third Skin, Eckersley Garden Architecture, Angus McIntyre and Tim Kreger.

Looking at how ideas recycle and morph over time, this project looks 41 years into the past to see 41 years into the future.

Multiplicity

John Wardle Architects and Stefano Boscutti.

Growth is no longer on its periphery but at our heart. Melbourne has grown not out, but up and down. In the future our city will tell multiple stories. A bundling of narratives and possibilities.

How Does it Make You Feel? (HDIMYF)

Ben Statkus (Statkus Architecture), Daniel Agdag, Melanie Etchell, William Golding, Anna Nguyen and Joel Ng.

Based on the premise that gravity is able to be controlled, fundamentally changing the way structures are realized and opening up the possibility of floating cities.

Ocean City

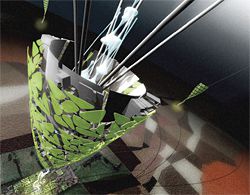

Arup Biomimetics—Alanna Howe and Alexander Hespe.

Tackling the large-scale migration of the Australian population from land to sea, necessitating a rise in biomimetic practices. Image Alanna Howe.

A City of Hope

Edmond and Corrigan—design: Peter Corrigan (everything); realization: Michael Spooner (and support).

A specialist city of 50,000 located on the boundary of Little Desert National Park in the Wimmera region of Victoria.

Sedimentary City

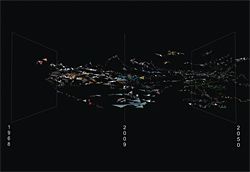

Brit Andresen and Mara Francis.

The sedimentary city of Brisbane is layered city-on-city, its layers existing in time and in space. New layers carry the trace of past cities with potential to draw in missed fragment catalysts.

Time Slice (left) made of parts reproduced from: Sidney Nolan, Death of Sergeant Kennedy at Stringybark Creek 1946, National Gallery of Australia; Arthur Boyd Nebuchadnezzar on fire falling over a waterfall, 1966–68, Bundanon Trust; Above Photography South-Brisbane-004825; John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland Neg: 185828; State Archives QLD; BCC eBIMAP, Ian Smith Hometown Series; Peter Cook Sleek Tower Verandah Tower Brisbane 1984; Andresen O’Gorman, Mt Nebo House, Rosebery House; Norman Lindsay Female Figure Holding her Breasts, Norman Lindsay Gallery and Museum.