South-west view showing the aluminiumclad west facade and the folded, coloured south facade, facing the Systems Garden. Image: John Gollings

Looking east along Tin Alley with the pleated west end of the north facade in the foreground. Image: John Gollings

The split, serrated west facade signals to similarly skinned buildings in the middle distance. Image: John Gollings

Detail of the glazed brick north facade. Image: John Gollings

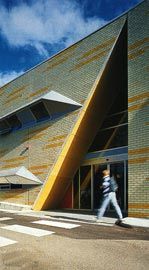

The main entry on the north facade is achieved through a triangular opening that barely fits within the dimensions of the wall. Image: John Gollings

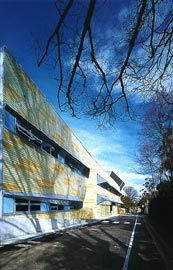

The distinctly different language of the south facade, seen across the campus gardens. Image: John Gollings

The south side of the building cranks around a tree, generating a sheltered outdoor space and recalling the radial geometries of the System Garden. Image: John Gollings

The intricate fenestration of the folded, pleated south facade. Image: John Gollings

View from the entry. The building narrows to five metres at this point, seeming to dissolve into the garden beyond. Image: John Gollings

Overview of the south facade. Image: John Gollings

View from the upper level over the garden and down the corridor to the east. Image: John Gollings

Looking down the stairwell to the ground floor foyer. Image: John Gollings

Lyons has recently completed a new wing to the School of Botany at the University of Melbourne campus in Parkville. Located on the west end of Tin Alley, near Royal Parade and adjacent to University House and the old botany Systems Garden, the building houses postgraduate research facilities on two levels. It is part of an oeuvre that includes a large number of teaching buildings. What might this building teach us?

Some time ago, Simon Anderson published “Neural Architecture” (Transition 49/50, 1996), an essay that explored the effects of visual perception and its application in architecture. It is worth pursuing these ideas again in the light of the botany building and other Lyons projects. “Neural Architecture” describes how our perceptual systems are able to compose information from relatively disparate sources, editing and assembling them in the brain. This process is quite unlike, say, the production of a photographic image, and it has significant implications for our understanding of buildings. Certain architectural strategies might elicit “super neural responses” when they interfere with visual conventions. They also test how small a visual cue we need in order to receive information, and how, by extension, we can assemble an authentic urbanism from the thinnest of contexts – a real place, but without depth, texture or detail.

Anderson discusses techniques such as extreme flush-ness, false shadows, false depth, colour and pattern that are at odds with the associated formal gesture. Since the publication of that essay, Lyons has pursued the architectural-surface-as-image over a number of scales. At the Sunshine Hospital extensions, we are asked to visually assemble a solar flare rendered at the scale of the brick. This is extremely stimulating.

Then, the end of the entire wing is repeated at a smaller scale, and in a flatter, simpler fashion. Our ability to recognise the repetition stimulates this sense of visual editing.

In the VUT Plumbing School at Sunshine, clouds are rendered across the facade at the scale of a large panel. It is remarkable how convincingly this most subtle of natural forms can be rendered at such a crude scale. An extremely fine grain covers the surface of the VUT Online Training Centre at St Albans. This extends from the digital dot of the printing process to the larger scale of the repeating pattern, the panel, and the facade openings. The elevation is processed as the eye runs up and down along each scale.

Many of these projects depend on the distant view to maximise their effects.

Indeed, the strategy invokes the power of the object far away, thus proposing a real urbanism for the open panorama of the highway. Squinting (as though in sunshine) seems to simulate that distant view.

In contrast, the new botany wing fits into a tight site on the University of Melbourne’s established campus, bounded by buildings and foliage. The site is heavily imbued with contextual agendas, and the design process seems to have negotiated these with great vigour. This has produced an array of references from within the immediate campus – a series of contextual inflections and surfaces are collapsed into a small but intensely differentiated form.

The four distinct faces of the building force a process of scanning and mental reassembly at the scale of the whole wall. In this process we might re-collect a whole slab of campus and city as well. The north facade fronts Tin Alley, and the hedge opposite, in patterned glazed brick. The bright solar colouring of the Sunshine Hospital facade is transposed in this location to a botanical foliage green, mirroring the hedge.

Turning the corner around a steel angle, the glazed brick gives way on the east side, facing University House, to a blank wall of light-brown brick. This material can be read as a convention not only for the Modern campus, but also for other Modernist institutional buildings such as the great public hospitals nearby.

Similarly, aluminium facades have become a signal of the bigger-scaled, more commercially skinned campus buildings of recent years. Where campus buildings of the 1950s may be compared with the teaching hospitals of the welfare state, the contemporary campus is constructed like commercial office space. The west end of the Botany building is clad in this material, and signals directly to similarly skinned objects visible in the middle distance. The aluminium figure, though, is frayed into two halves, and savagely serrated as the pleating of the north facade is extruded through to the north-west corner.

On the south facade, a fourth language is developed. This side faces a green space and the remains of the botanical collection of the Systems Garden. This face is intensely glazed. Patterned, densely framed and folded deeply in section, it is almost Gothic. It cranks too in plan, cutting into itself and splitting into a glazed link which joins the previous wing. This cranked geometry inflects around the pair of large adjacent trees and registers a trace of the radial gardens. The radial geometry of the gardens is also marked as red rays on the floor within the building. More explicitly, the glazed wall bears a resemblance to the glasshouses across the garden, with their pitched roofs and small-scale glazing.

The building, then, is a four-sided material debate – two fronts and two backs carefully collect and arrange the specimens around them, encoding them with diverse readings. The neural challenge is to gather these and hold them in a single object.

In scale, the botany wing is tiny. In some ways it appears to be a miniature of a large Modernist slab block. It oscillates between this scale and domestic gestures; it is both a big house and a small institution. At points all over its surface, the building seems as though it could have been much larger. The glazed brickwork of the north facade seems domestic – like a Howard Arkely image of a house, or Venturi Scott Brown’s Brant House in Greenwich, Connecticut (1972). The triangle cut from this facade to form the entry opening barely fits: deliberately too big, it nearly splits the wall in two. At the west, the building lifts off the ground onto piloti, but only barely and momentarily. The south fenestration is intensely small, with small awning sashes and diagonal braces adding to the density of mullions.

In plan, the floorplate compresses to such an extent that it almost disappears at the entry. Here, the building is about five metres deep, forming a foyer which – glazed both sides – visually links the remnant System Garden through to Tin Alley. There are enough cues here to encourage us to squint, and imagine a much larger institution – one that could hold a domestic scale and an institutional monumentality in the same place. Like a souvenir, the botany wing intensifies thoughts of a big public building where we might also feel at home.

Contemporary buildings have long lost their ability to accurately measure the urban significance of what they hold. Important institutions are hidden, unimportant ones are overblown. Architects too often pass up big opportunities, so that others have to intensify their efforts, compressing them into small buildings on the fringe. If we can understand the city as a series of neural triggers assembled through a fiction, then the task of making monuments is widely dispersed. The Lyons buildings are so good precisely because they take this task on. A journey along the Ballarat Road and on to Sunshine then St Albans can pass several years of Lyons’ work, representing a rigorous study of the expanded scale of our new suburban city.

Urbanism can be done wherever the view pops up – that is the reality of the “Brand New City”. It is worth remembering, as Melbourne’s BHP tower rises, and as the botany building nestles into its urbane campus, how much the suburban city is teaching the old centre. With the University of Melbourne’s new botany wing, we again see a refusal to measure the potential of architecture by its prominence – either by size or by location, or by the constraints on it. This is a profoundly optimistic position.

Credits

- Project

- School of Botany, North-West Extension, University of Melbourne

- Architect

- Lyons Architecture

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Project Team

- Corbett Lyon, Cameron Lyon, Carey Lyon, Hamish Lyon, Clare Connan, Sergio Montano, Tina Nabb, Charles Wright, Emma Young

- Consultants

-

Acoustic engineer

Arup

Building contractor Kane Constructions

Building surveyor PLP Building Surveyors & Consultants

Landscape architect Urban Initiatives

Quantity surveyor Sinclair Knight Merz

Services engineer Arup

Structural, civil & facade engineer Connell Mott MacDonald

- Site Details

-

Location

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

- Client

-

Client name

Melbourne University Property and Buildings, for the School of Botany