An oblique view of The Gauge showing the wrapping of the atrium wall up and over the roof. Image: Emma Cross

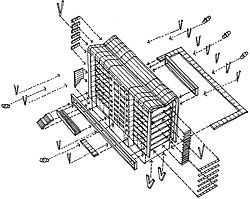

Axonometric sketch studies from the aspirational scheme of 2006.

Casual meeting spaces punctuate the office layouts. Image: Shannon McGrath

One of the workstation bays. Image: Shannon McGrath

The curved concrete walls enclosing the meeting spaces on each level. Image: Marcus Clinton

Looking from one meeting room to another. Image: Marcus Clinton

The ground-level foyer with the green wall on one side, and feature wall decorated with reclaimed timber on the other. Image: Emma Cross

Looking up the glazed lift shaft that rises up the atrium. Image: Emma Cross

When the word “sustainability” first entered our architectural vocabulary late last century, it was usually exemplified in isolated dwellings, remote houses or weekenders built by enthusiasts or committed architects, for whom necessity gave rise to opportunity. In the commercial sector, however, it was mostly a distant but unrealistic aspiration. Everybody wanted to do it, of course, but the technology had not been tested, or the design skills were not available, or the costs were too high for clients to wear; in short, the risks were just too great to warrant the innovation necessary to make large-scale buildings work better in environmental terms.

Fast forward to now, and we find the latest sustainable building is the new Melbourne headquarters of one of Australia’s oldest and largest property development companies, Lend Lease. Known as The Gauge, the building has been awarded a 6 Star Green Star Design Stage Certified Rating by the Green Building Council of Australia, as well as VicUrban’s Award of Excellence for Ecologically Sustainable Development.

How did this happen? There are several reasons. Firstly, the rating system itself has created something of a competitive benchmark, allowing those who commission or lease projects to demand a high level of performance with just two words: “five star” or “six star”. Secondly, the leadership shown primarily by local governments has proven that office buildings can be made more sustainable. And thirdly, publicly listed companies are realizing that sustainability plays an essential part in their identity, allowing them to demonstrate corporate social responsibility to employees, clients and the wider community.

Designed in-house by architect Darren Kindrachuk, The Gauge continues a commitment to sustainability first demonstrated by Lend Lease at 30 The Bond in Sydney. The aim of The Gauge is to show that a six-star rating can be achieved within market standard development costs for a building of its type – in other words, to demonstrate the commercial viability of sustainable buildings. The result is a highly engineered and reasonably elegant solution to the interconnected problems of function, construction and environmental performance. In The Gauge, every detail, every dimension, every material is precisely designed to minimize costs and maximize star rating.

Compared to the nearby banks (NAB and ANZ), this is a relatively small building: around 10,000 square metres, comprising six floors of office space plus ground-floor retail and car parking. The absence of a central core makes for a linear layout, with rows of desks down the middle of the floor plate, separated from the line of circulation by meeting rooms. There’s a reception desk at one end and utility and kitchen areas at the other. The circulation side is then wrapped by an atrium wall, enabling the stack effect to draw air from each floor plate up and out through the roof. The atrium gives a sense of height and space, but its principal function is to draw air up and out of the building. Combined with passive chilled ceiling panels for cooling, this avoids recirculation, giving much better levels of indoor air quality and improving the perceived freshness of the air.

From the outside, the atrium wall wrapping up and over the building provides the main decorative element, with yellow steel framing, galvanized corrugated iron cladding and relatively transparent glazing allowing views to the interior. At the Bourke Street end, the atrium space provides vertical circulation through glass lifts, leaving the other end for informal activities such as reading, eating and relaxation. On level one, this area opens to an outdoor deck for social events. Wet services (toilets and fire stairs) take up the middle third of the atrium, making them easy to find and giving access to daylight to help reduce energy use.

Each floor, measuring 70 x 21.5 metres, is made up of seven workstation bays, each containing a pair of large desks seating three on each side. These are surrounded on the perimeter by breakout spaces, meeting rooms and a number of individual workstations, making a total of ninety-six people per floor. Each bay is defined by an area of exposed ceiling where the chiller panels can be seen, which helps to avoid the feeling of endless rows of identical desks. This is further enhanced by task lighting that helps to define each large desk and the occasional partition hanging from the ceiling. On this side, a storage wall with plants above helps to define the meeting rooms, which are then articulated on the circulation side as a series of curved concrete walls. Gaps between the meeting rooms mark access to the workstations, minimizing interruptions from through traffic.

At ground level, a cafe welcomes workers and guests, decorated with a green wall heralding the building’s environmental aspirations. Near the lifts, walls are decorated with reclaimed timber, stencilled with words and images to give the appearance of contextual patination. A pair of giant, Y-shaped, steel pilotis dominate the foyer space, adding to the industrial feel and helping to minimize interruption to the outer wall of glass. Behind the cafe, and extending under the adjacent street, is a car park space, along with bike racks and shower facilities. Here also is a blackwater treatment plant that returns water for non-potable uses, while an underground tank collects rainwater from the roof for distribution to the adjacent park. On the roof, a cogeneration plant provides heat and power for the building, linked to heat exchangers to minimize waste heat from exhaust air.

Clearly we have come a long way since the days of the remote shack as the paradigm for sustainable architecture. Now The Gauge, as its name proclaims, sets a new level by which environmental performance can be evaluated. But there is something in this building that reminds me of a shack: elegant, elemental, self-sufficient and precisely engineered to meet interconnecting requirements of function, structure, construction and environmental performance.

This is not a building that will rewrite the history of architecture in Australia, but it does take us back to the pioneering days of Lend Lease, when founder Dick Dusseldorp brought a European sense of social democracy to the burgeoning Australian commercial property industry. 1 The Gauge is, perhaps, the most advanced version of its type: the low-rise, high-rating commercial office that provides a good place to work while also activating the surrounding urban space. It shows, rather precisely, that sustainability initiatives can be achieved within the limits of commercial constraint.

Whatever is not included – photovoltaic power, for example – is either not yet financially viable or not sufficiently accounted for in the current Green Star rating system. As such, The Gauge is something of a snapshot of the current state of play, in terms of technology, development finance and environmental performance. The building industry may have a lot to worry about in the next few years, but I hope it continues to integrate and develop these three areas and respond to the challenge that Lend Lease has presented with its new headquarters. The Gauge is a very measured response to the current climate; let’s hope it is also a good measure for what comes next.

Scott Drake is a senior lecturer in the Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning at the University of Melbourne.

1. See Lindie Clark, Finding a Common Interest: the story of Dick Dusseldorp and Lend Lease (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002) and Mary Murphy, Challenges of Change: the Lend Lease story (Sydney: Lend Lease, 1984).

Credits

- Project

- The Gauge

- Architect

- Lend Lease Design

Millers Point, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- Project Team

- Darren Kindrachuk, Grand Cheng, Kevin Ellis, Dwight Torrevillas, Mark Baker, Todor Spasovski, John Dundovic, Bob Gonano.

- Consultants

-

Blank Role :: The Gauge

Acoustics Bassett Acoustics

Building surveyor PLP Building Surveyors & Consultants

Construction manager Lendlease

Developer Lend Lease Development

Electrical engineer Lend Lease Design

Facade engineer Aurecon

Hydraulic and fire services engineer Lend Lease Design

Mechanical engineer Cundall Australia

Project management Lendlease

Structural engineer Lend Lease Design

- Site Details

-

Location

825 Bourke Street,

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built