REVIEW HELEN NORRIE PHOTOGRAPHY CHRIS WILSON, BART MAIORANA

Review

Evening view of the Forest EcoCentre seen from the main road. Photograph Chris Wilson.

Eastern elevation, with entry. Photograph Bart Maiorana.

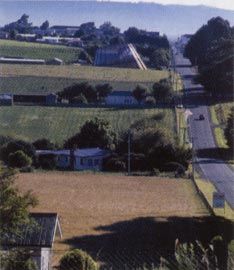

The familiar yet foreign form of the EcoCentre seen amid rural infrastructure on the approach road to Scottsdale. Photograph Chris Wilson.

The entry space between the conical form of the conservatory and the timber-clad office building. Photograph Bart Maiorana.

The cafe housed beneath the timber volume, with seating in the interstitial public space. Photograph Chris Wilson.

Looking up into the thermal vent through which warm air rises before being pushed back down into the office by the large fan at the top. In summer the propeller pulls cool air through louvres.

The dramatic space of the conservatory. Photographs Bart Maiorana.

Details of the conservatory structure.

Details of the conservatory structure.

Details of the conservatory structure.

Details of the conservatory structure.

ON THE OUTSKIRTS of Scottsdale, in north-east Tasmania, a recent building by Morris-Nunn and Associates (MNA) provides an interesting contribution to the question of interpretation. The Forest EcoCentre was born out of the need to construct new offices for Forestry Tasmania, and the recognition that this could also provide community and tourism facilities for the area. Approaching the town, the building sits in an open field, an object in the landscape that creates an iconic gateway, “dressing up” the site of a former forestry petrol storage centre. It is an intriguing addition to landscape, one which fits within the familiar typology of rural buildings where farm sheds and out-buildings sit in strong contrast to the cleared open landscape. Yet it is also rather strange. At once familiar and foreign, this curious conical form invites closer inspection.

Robert Morris-Nunn has a canny understanding of the broader potential of design problems. He constantly reconsiders the clients’ needs and presents them with propositions that extend beyond the pragmatics of the brief. In developing projects, Morris-Nunn builds a conversation between a team of consultants and colleagues, allowing ideas to be explored, tested and expanded. In the case of the EcoCentre, MNA worked with Jim Gandy of Gandy and Roberts, a brilliantly creative engineer with a passion for a challenge, and Ché Wall from Advanced Environmental Concepts in Sydney. The result is a fine building which engages with the polemical issues of “environmental sustainability”, in which Forestry Tasmania is often embroiled.

Tasmania is Australia’s most heavily forested and least populated state, with 3.3 million hectares of land (half the state) categorized as forest reserves and privately owned or production forests. The management and use of this forest is the source of constant debate between conservationists concerned about the long-term ecological issues that attend forestry practices and locals whose livelihood depends on the industry. According to Forestry Tasmania figures, forestry contributes about $1billion each year to the Tasmanian economy, and represents 20 percent of the state’s total manufacturing employment and 24 percent of its total industry turnover. In a state with a rather fragile economy underpinned by industry, the arguments surrounding forestry activities are ongoing and often intense.

Some conservationists are hostile towards Morris-Nunn’s involvement in this project, suggesting that any association with Forestry Tasmania signals an acceptance of their practices. This passionate stance was reflected in the recent controversy surrounding the fledgling arts festival, 10 Days on the Island, which was this year partly sponsored by Forestry Tasmania. Several artists withdrew from the festival and staged a parallel festival to protest Forestry’s involvement. (This alternative exhibition incidentally included a collaborative piece of work by furniture maker Kevin Perkins and Robert Morris-Nunn.) Many people who did attend the festival wore black armbands to signify that their presence was in support of the artists and not the sponsor.

The EcoCentre makes a considered contribution to this debate. Yes, the strongly iconic building could be considered complicit with Forestry’s continuing public relations exercise. However, the design team has also used this project to explore issues of energy efficiency in office buildings, and in doing so it has involved Forestry Tasmania in significant research and development into sustainable building practices – a field that is widely discussed but perhaps less often fully carried through in built work.

Initially, the client intended to construct two separate buildings – an office building and a visitor centre – side by side. By combining the two, one inside the other, Morris- Nunn has also produced a recognizable identity for Scottsdale and for Forestry Tasmania. The conical form is generated by a desire to produce an efficient surface area in relation to the internal volume, with the truncated cone oriented to maximize the northern sun. The offices for Forestry Tasmania are housed in a timber-clad cube within the centre of the conical conservatory, and the interstitial space contains the visitors’ facilities including a cafe and gift shop and a range of interpretative installations.

The conservatory provides a dramatic spatial experience, which creates an ambiguity between inside and outside, but it is also an intrinsic part of the building’s overall thermal performance. Air inside the building is heated via sun penetration into the space. This warm air rises through the central “thermal chimney” to heat the offices on the upper levels, and a down-draught propeller at the top of the chimney drives the rising heat back down to the lower levels. In summer the fan is reversed, cooling the building by drawing fresh air through louvres in the external envelope.

The building is very successful in environmental terms, although an experimental project of this kind does require constant tuning. The EcoCentre was constructed for less than a conventional office building ($1420 per square metre compared with $1600 in an equivalently remote location) and uses arsenic free plantation line. Early indications suggest that operating costs will continue to fall below half those of a conventional office building. Finally, it is a carefully detailed, refined and beautiful piece of architecture.

The iconography of the building is commercialized through souvenir fridge-magnets and key-rings, which are sold in the gift shop, along with a range of products from the north-east and surrounds. The cafe, with its simple menu of fine food, also means that the EcoCentre is now a popular destination for lunch, either as a rest stop along the route to the east coast, or as part of a day trip from Launceston through the picturesque winding forest roads. This new visitor facility has reconfirmed Scottsdale as a destination on Tasmania’s tourist trail. By making a place that acts as a catalyst for tourism, it demonstrates how a single building can expand the possibilities for understanding a place. The EcoCentre has become an important part of the community, acting as a tourist information centre for the region with enthusiastic voluntary staff keen to pass on local knowledge of the area.

The formal interpretatiThe formal interpretation aspects of the building are limited to a rather conventional series of DVD screens, with “interaction” restricted to the visitors’ ability to push buttons to select stories about the building, the local community or forestry practices. It also includes a rather curious “forest installation”, housed in a dark gap on the southern edge of the building. Initially the design team developed ideas about the interpretation that could be incorporated into the building; but the subsequent exhibition was developed by Forestry without consulting the architects. No doubt the current exhibits are of interest to visitors, who obviously enjoy both the factual context of the displays, and the opportunity to dwell longer in the building, but there is a question of how these could be made both more engaging and be more successfully integrated into the space.

In so many instances along the “tourist trail”, site interpretation is produced by a series of frighteningly familiar “wallpapered” panels with assorted graphics and lengthy text panels. The Scottsdale EcoCentre demonstrates that visitors centres can play a more important and subtle role in interpreting a place. The architecture of the EcoCentre engages visitors in the broader issues of the environment and sustainability by allowing them to experience and understand the principles of passive design in a finely executed and very memorable building. The facility has become a favourite public space in the community, and this encourages visitors and locals to further develop an understanding of the place and its surroundings.

But, of course, the final resounding memory the building provokes is the visual association that has been attributed to it by some, that of a tree stump in a felled landscape, allowing us to ponder that, in more than one way, the building can be considered as a “symbol of forestry’s contribution to the environment”.

HELEN NORRIE IS A LECTURER IN ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TASMANIA. FOR A THOROUGH EXPLANATION OF THE PRINCIPLES AND DETAILS OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL STRATEGIES IN THE SCOTTSDALE FOREST ECOCENTRE REFER TO RORY SPENCE’S EXCELLENT LISTING IN THE BDP ENVIR

Project Credits

FOREST ECOCENTRE, SCOTTSDALE

Architect Morris-Nunn & Associates—Robert Morris-Nunn and Peter Walker. Thermal engineers Advanced Environmental Concepts—Ché Wall and Nicholas Lander.

Structural engineer Gandy and Roberts—Jim Gandy.

Electrical engineer Tasmanian Building Services—John Calder and Gosta Blichfeldt. Fire engineer ARUPS—Per Ollson and Jan Ottosson. Cost control Stanton Management Group—Patrick Stanton with Davis Langdon Aust. Builder Fairbrother—Chris Wilson and Brendan Crack.