On top of an abandoned 1900s fort on Porter Hill, Tasmania, sits one of the great modern houses of Australia: Fort Nelson. The Hobart residence of the late J. H. Esmond Dorney, a Robin Boyd contemporary, has been purchased by Hobart City Council. More than sixty years after the original house was built, and after Dorney’s son Paddy and his family lived for a period in the latest of three versions, the Fort Nelson property is being considered for public viewing and to host gentle, public events, appropriate to its scale and site.

The story is comparable to that of Boyd’s own family residence at Walsh Street in South Yarra, Victoria. As a new resident of Melbourne, I have had the pleasure of visiting some of Boyd’s houses, including the Walsh Street House, which is akin to an elegant urban tent, enclosing a tranquil courtyard. The house is analogous with a living, fully functioning time capsule and, in that context, I was struck by the architect’s pursuit of a new lifestyle paradigm through an elite expression of space, material, furniture and art, in relationship to landscape.

Similarly, both prior to and since Hobart City Council’s acquisition, the Dorney house has been well visited and much admired. Many eminent Australian architects and academics (Roy Grounds, Glenn Murcutt, Rory Spence, Richard Leplastrier, Richard Johnson, Karl Fender and Carey Lyon, to name just a few) have made the pilgrimage along the steep, single-lane road with its sharp, hairpin bends, rising high above Sandy Bay.

I am fortunate to have visited Fort Nelson on several occasions – first meeting J. H. Esmond in about 1982 after I called him with a request to see his house. He was seventy-six years old, yet still working in relative isolation on his hilltop, and I was just finishing my architecture degree. Generously responding to my interest, he picked me up in Churchill Avenue, well below Fort Nelson, and we ascended the steep road quite swiftly in his sports car, for a brief, yet memorable, private visit.

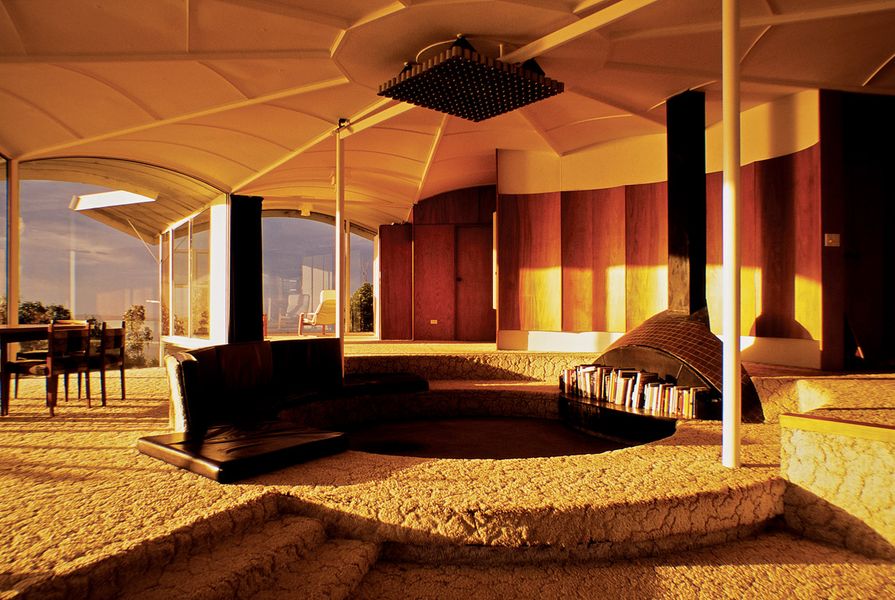

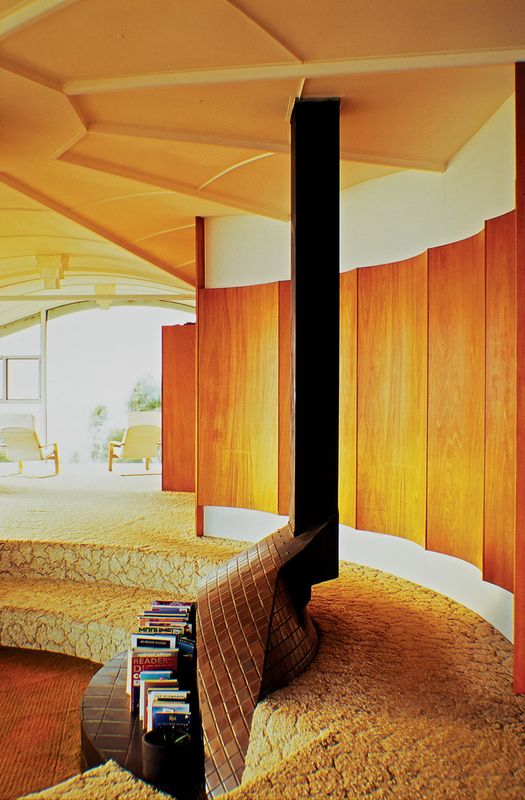

Built-in seats encircling the fire pit eliminate the need for furniture.

Image: Ray Joyce

Dorney’s home, built when he settled in post-World War II Tasmania, is one of his defining works. His other recognized Tasmanian buildings include the Young House, popularly known as the Butterfly House, at Sandy Bay; Saint Pius X Catholic Church at Taroona; and Snows Drycleaners at Moonah. Lesser known are many other significant buildings, including Victorian projects such as Sandringham and District Memorial Hospital, Caritas Christi Hospice at Kew, the Cole House in the Dandenong Ranges, and a number of apartment buildings, particularly around Elwood.

Dorney actually built three houses on the Fort Nelson site. The current house, which sits on a former circa 1904 gun emplacement, was built in 1978. Prior to that, according to Paddy Dorney, the first house was built in 1949 on the southern gun emplacement, and then a second in 1966 on the northern gun emplacement. Both of the earlier versions were destroyed by separate bushfires. The current house is, in effect, a reconsideration of the 1966 version. It is worth pausing at this point, with respect, to consider Dorney’s resilience, tenacity and strength in rebuilding twice. Having endured being a prisoner of war during World War II and hospitalization upon his return he was then challenged by the loss of his home and work to bushfires. Remarkably, Dorney simply chose to improve his original design.

The essential idea, plan and form of the 1966 and 1978 versions are quite similar, with minor variations to bedroom arrangements, entry sequence and the location of the kitchen. The 1966 house had Dorney’s office “lookout” perched above the fireplace and the kitchen was located in the south-eastern corner, while in 1978 the office was moved to below the living room and the kitchen was moved to the north-west. At this latitude, almost 43 degrees south, with the sun rising about 22 degrees at the winter solstice from the north-east and setting in the north-west, the plan orientation does not get any better.

The solid blockwork base wall connects into a 1900s gun emplacement.

Image: Ray Joyce

The current house form is expressed by a series of segmented petal-like roof vaults that sit on the thinnest of steel columns, with the regular dodecagon plan embracing, capturing and inevitably succumbing to a panoramic view of the Derwent River estuary and Southern Ocean beyond. The site is unusual, impenetrable, commanding and magnificent. But words can’t do it justice – it is almost beyond description.

A solid blockwork base wall amplifies the fine steel detailing, defining the floor platform and extending the solidity of, and connecting into, the former gun emplacement as a foundation. Frameless glazing, beaded into the elegant steel frame, effortlessly defines the unfurled plan and gentle roof vaults hovering above.

Remnants of the first house built in 1949 on the southern gun emplacement.

Image: Houses

Spatially, this house is incredibly modest. It is almost room-less, with two of the three bedrooms linked as a corridor to the bathroom. Yet the way that this house embraces its extraordinary landscape prospect, both down and out from it, is astonishing. The Fort Nelson house is a testament to Dorney’s mastery and humility: the grace and uncomplicated experience of the building are integral to its breathtaking outlook and landscape.

The first bedroom appears to be almost incidental, screened by a fluted plywood wall, while the kitchen and third bedroom seem to slide off the plan. The viewing platform/living room, with a sunken fire pit, almost denies the use of furniture, deferring to a built-in seat and steps encircling the fire. This is not a house that requires much furnishing. Upon these tiers of seating, the Dorneys could easily accommodate many guests at family events and weddings, or watch the full majesty of the Southern Lights in seclusion around this internal “campfire.”

Externally, the Fort Nelson house is perhaps best appreciated from afar, either obliquely in silhouette, or well below from the Derwent River, given the steepness of the immediate terrain. Only then, from that distance, can Dorney’s masterful understanding of the military fort site (and the placing of his house on the impenetrable brow) be fully appreciated. The vaulted roof honours the shape of the immediate tree canopy, and the silhouette profile becomes part of its landscape.

Fort Nelson sits high above Sandy Bay, with 360-degree views of Hobart.

Image: Ray Joyce

Fort Nelson is a “house of platform and hovering roof” in the generic sense, yet it is without large overhangs. Its eaves are positioned precisely to allow seasonal sun penetration. The structure is neoclassical, in terms of its positioning and command of a landscape it deeply respects. Dorney’s house returns us to the worth of architecture and, like Boyd’s work, speaks of our humanity and identity – about who or what we are, through how we build and live on the landscape.

The transfer of the Fort Nelson property into public ownership is confirmation of its significance in terms of the site, landscape, architecture and architect. Additionally, the transfer is indicative of the Dorney family’s altruistic attitude – releasing, for public benefit or common good, what was essentially a magnificent, but once very private, sanctuary.

Almost three decades on from when I first met with Dorney at his home, I still consider Fort Nelson to be one of the great modern houses of Australia. It is so light, yet so strong, modestly and deftly marking the landscape. Its fine structure embraces the rolling panorama of weather conditions that characterizes southern Tasmania: from fair skies with strong sunshine, or soft wintery light, through to the intense, blustery weather of southern fronts, squalls and storms.

Although the journey to Fort Nelson is now somewhat reduced in quality, mainly due to the upward march of suburban sprawl, the once closely held secret of Dorney’s humble masterpiece remains well worth the trip.

Architect

Esmond Dorney 1906–1991

Practice profile

J. H. Esmond Dorney studied architecture at the University of Melbourne and worked for Walter Burley Griffin before setting up his own practice. After the war, Dorney moved to Tasmania and worked in the “adventurous post-war traditions of Roy Grounds, Robin Boyd and others in Melbourne.” (Architecture Australia, April 1992, p. 10.)

This review is part of the Houses magazine Revisited series.

Credits

- Project

- Fort Nelson House

- Architect

-

J H Esmond Dorney

- Site Details

-

Location

Hobart,

Tas,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Type New houses

Source

Project

Published online: 23 Aug 2012

Words:

James Jones

Images:

Houses,

Ray Joyce

Issue

Houses, February 2012