The year 2021 marks the 50th anniversary of the death of Robin Boyd, who, as the Robin Boyd Foundation states, is “arguably the most influential architect there has ever been in Australia.”

Born on 3 January 1919, Boyd, in his short life, made an indelible mark on Australian architecture and culture through his weekly columns in The Age and the Herald, his directorship of the Small Homes Service (1947–53), and more than a dozen books, including seminal works such as Victorian Modern (1947), The Australian Ugliness (1960) and Living in Australia (1970).

Boyd designed churches, colleges, motels and the Australian pavilions at Expo 67 in Montreal and Expo 70 in Osaka. But perhaps his most enduring legacy is in residential architecture. Around 100 houses were built from his designs, including the widely celebrated Featherston House (1969), Baker House (1966) and his own Walsh Street House (1958) which is now the home of the Robin Boyd Foundation.

Boyd received the Gold Medal from the Royal Australian Institute of Architects in 1969, and in 1971 he as appointed a Commander of the British Empire (CBE). In the same year, he was invited to judge an international competition to design a new building that would house members of the British parliament.

On 16 October 1971, Boyd died suddenly from an infection he caught while on a world tour. In his death notice, fine arts professor Joseph Burke of the University of Melbourne remembered Boyd as “a creative architect of great originality.”

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of his death, we look back some of his houses that demonstrate his ideas about architecture. As he wrote in Living in Australia, “a good piece of architecture is a building based on the concept of good living conditions […] good living is the recognized motivation behind practically all thoughtful architecture and design.”

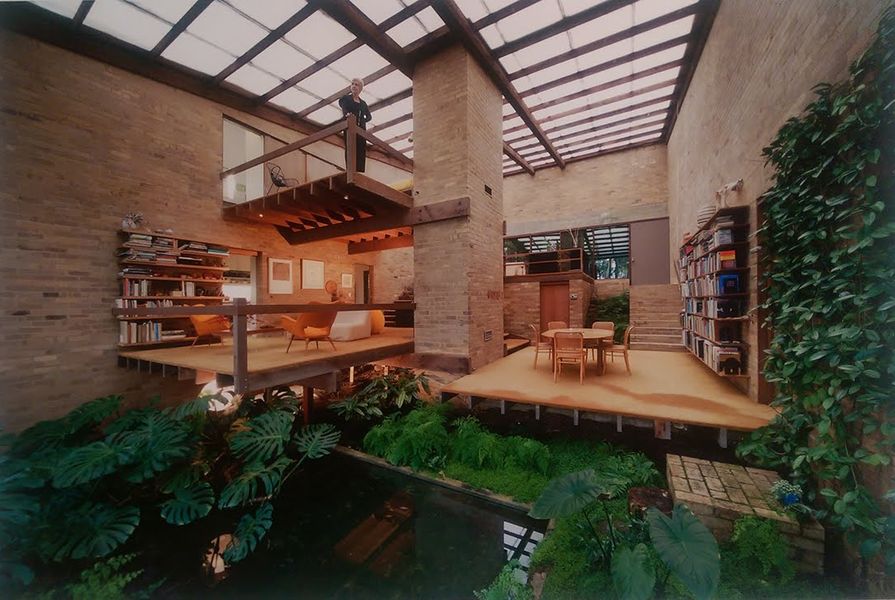

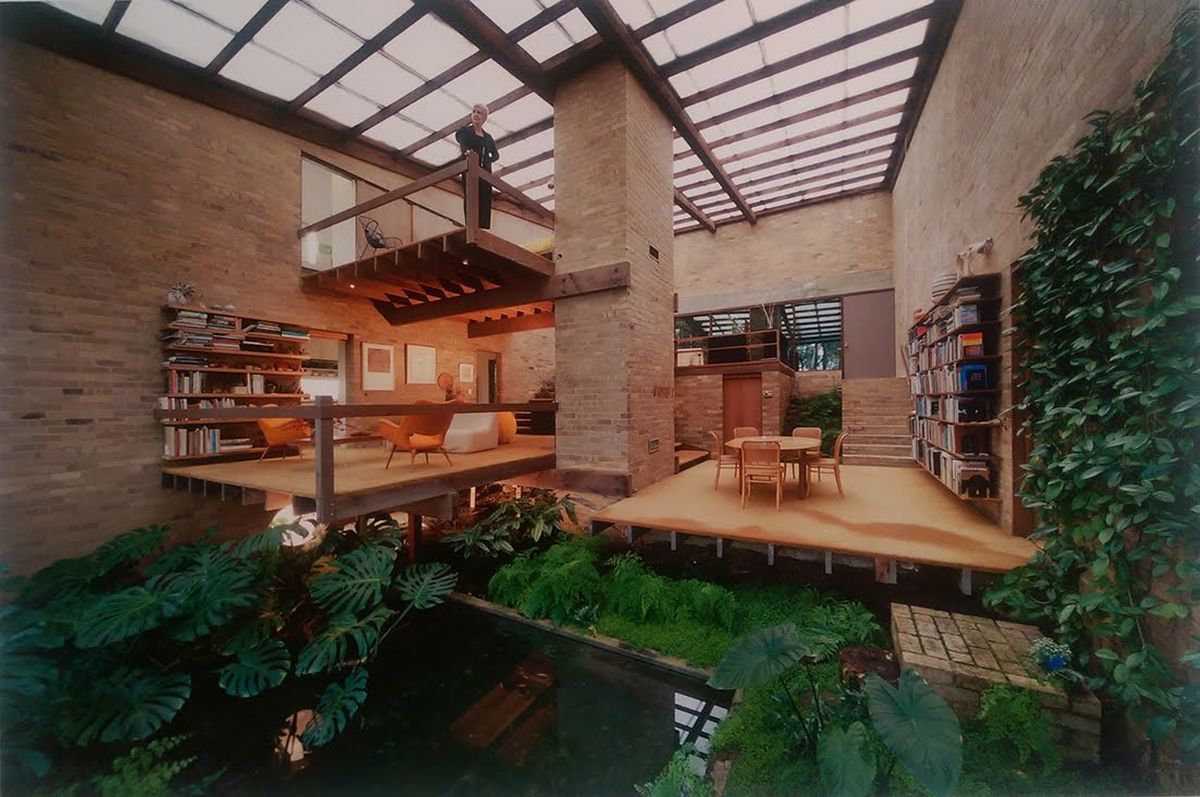

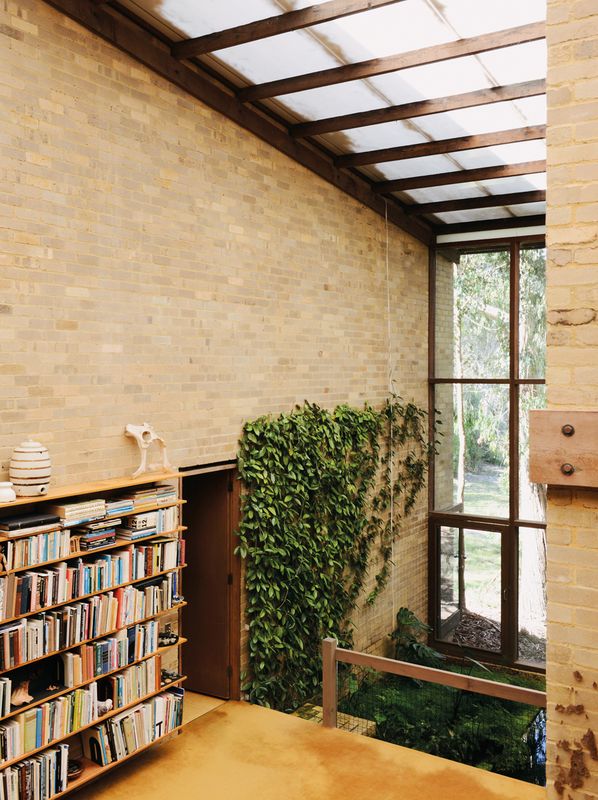

Featherston House (1967–69) by Robin Boyd.

Image: Lauren Bamford

Featherston House (1967–69)

Featherston House is one of Boyd’s most seminal designs, along with his own house, Walsh Street House, which is now the headquarters of the Robin Boyd Foundation. The house was the home of Mary and Grant Featherston, renowned designers in their own right. The house consists of a series of living platforms which float above an indoor garden. In this essay Mary reflects on more than 50 years living in this “incredible” space, and the legacy it created for flexible and adaptible living in the suburbs. Read more…

Blott House (1956) by Robin Boyd.

Image: Dianna Snape

Blott House (1956)

Located in Melbourne’s Chirnside Park, this house encapsulated some of Boyd’s forward-thinking ideas, from his preoccupation with the window wall to a fascination with the “conflict between the opposed desires of privacy and freedom, between the cell and the great hall, both of which we all need to be able to experience, on our own terms, at our own timing,” as he wrote in Living in Australia. The interior of the house includes open living/dining spaces that give the sense of living in an oversized artist’s studio, a radical concept in 1956 which would mark the end of formalized living spaces. “The Blott House is testament to Boyd’s belief that a lot can be done with very little. It’s a true lesson for today,” finds Philip Goad. Read more…

Stone House (1953) by Robin Boyd.

Image: Sonia Mangiapane

Stone House (1953)

By 1953, Robin Boyd had established a name for himself through his directorship of the Small Homes Service. But his clients for the Stone House – young professionals with a penchant for the arts – didn’t want a Small Homes Service house. Boyd created for them a modest home wedged between two estates by Walter Burley and Marion Mahony Griffin, in Eaglemont. The open plan house, delineated by split levels rather than walls, reflected the owners’ progressive attitudes and accommodated the various permutations of family life – “a testament to its enduring qualities and [Boyd’s] ability to interpret their lifestyle,” writes Jacqui Alexander. Read more…

Lyons House (1967) by Robin Boyd.

Image: Peter Bennetts

Lyons House (1967)

The commission for Robin Boyd’s only Sydney project came from a reader of The Australian Ugliness. A young orthopaedic surgeon, Bill Lyons wanted a Spanish-style courtyard house with a swimming pool. The house Boyd delivered is as requested, albeit raised dramatically off the ground and appearing to cantilever on improbably narrow timber struts, as David Neustein finds. “Taking the plan, section and elevation of the Lyons House, we can draw a composite portrait of Boyd’s career. The plan of the house is as economical and rational as any of those devised for the Small Homes Service. However, the section of the house shows how adventurous and unconventional the house is, with living spaces suspended above ground to capture the view.” Read more…

King House and Studios (1952-64) by Robin Boyd.

Image: Dianna Snape

King House and Studios (1952-64)

Designed for a sculptor and an artist and built in three stages, the King House and Studios in Warrandyte “does not easily imply domesticity,” writes Nigel Bertram, “it makes us question, in fact, what a ‘house’ is.” The original one-room house includes a raised bay to the north labelled a “painting platform” and an underfloor space labelled a “food store” that has also been used as a workspace and studio, as well as a small bathroom, a porch and a bedroom that isn’t used as such. “The architecture of this house is flexible, affordable and inherently sustainable due to its longevity and adaptability,” Bertram writes. “[It] exemplifies the much discussed notions of ‘working from home’ and ‘ageing in place’ as self-evident, simple facts.” Read more…

Linden House (1964) by Robin Boyd.

Image: Adam Gibson

Linden House (1964)

The lesser known house is Boyd’s only work in Tasmania. The project was to involve a substantial and elegant makeover of the original farmhouse. He proposed a masterful integrated composition – a multipurpose glazed pavilion 14 metres long, 11 metres wide and 4.5 metres high, reminiscent of an enlarged Japanese bungalow. It opened toward the river at the front and extended outward to the rear, forming a giant pergola enclosing a pool courtyard. The original stucco house was reconfigured into a bedroom block. Read more…