<b>REVIEW</b> PETER KOHANE <b>PHOTOGRAPHY</b> ERIC SIERINS, JENNI CARTER

The new function space viewed across Andersons’ brightly lit void.

The settings devised by three distinguished architects – Vernon, Andersons and Johnson – each have their own integrity.

The front entrance in 1904. Originally published in the Journal of the Institute of Architects of New South Wales, April 1904, page 48.

The existing Asian Gallery is a podium for Johnson’s glass box.

Vernon’s vestibule in 1904. Originally published in the Journal of the Institute of Architects of New South Wales, April 1904, page 66.

The new pavilion glows like a Chinese lantern against the city.

The square glass panes are held in place by metal brackets in the shape of a lotus flower.

The restaurant is sited to emphasize the view.

The glass box can be seen as a counterpart to Vernon’s sandstone structure. Photograph Diana Panuccio.

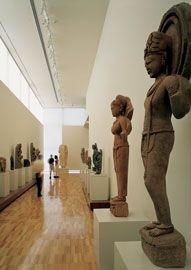

Asian galleries.

Asian galleries.

The Asian gallery spaces within the pavilion are suffused with light.

The Asian gallery spaces within the pavilion are suffused with light.

The Asian gallery spaces within the pavilion are suffused with light.

IN 1904, the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW) was featured in the second issue of the Journal of the Institute of Architects of New South Wales (the magazine that would become Architecture Australia). The building, designed by the Government Architect,Walter Liberty Vernon, included the extant porticoed west front, the vestibule and the gallery wing located to the south of the entrance axis. Now, one hundred years later, we can revisit the gallery on the occasion of the opening of a new pavilion for the Asian collections. This extension by Richard Johnson, of Johnson Pilton Walker, addresses current institutional ideals, while also engaging with Vernon’s scheme.

The building that Johnson worked with was the result of designs by Vernon and Andrew Andersons, the latter responsible for two major projects during the past thirty years, which added galleries, a cafe, a theatre and circulation spaces. It comprised five levels, most linked by escalators, and extended east across the available land. Johnson therefore built on the fabric constructed by Andersons. However, one of his primary concerns was the creation of a modern form that could speak as cogently about the institution as Vernon’s classical composition. Johnson’s contribution is an impressive translucent glass structure, providing more space for the Asian gallery directly below.

The pavilion has a celebratory role, informing the public of transformations within the institution. The AGNSW has elevated the once marginalized collections of Aboriginal and Asian art onto centre stage. Andersons’ extensions provided curators with space for Aboriginal art, currently displayed on the lowest level, in the Yiribana Gallery. His Asian gallery is two floors above, yet still below the entry level. These galleries are both removed from the monumental entrance front to the west and, along with the other spaces of Andersons’ schemes, they are within an understated exterior. Johnson’s approach is different. The existing Asian gallery has become a podium for the expressive new pavilion and its accompanying rhetorical statement. This is emphasized by the AGNSW website, which now shows the building from the south-east at dusk. Attention is focused on the glass form, which both glows and hovers above Andersons’ unobtrusive walls. It is a modern cantilevered structure that when lit looks like a Chinese lantern. A close inspection of the architectural details confirms the general impression: the walls are made of square glass panes, held in place by metal brackets in the shape of a lotus flower. A connection is made between architecture and the objects it harbours.

Raised above the ground sloping to the east, this glass box is on the AGNSW’s entrance level, and can be seen as a counterpart to Vernon’s sandstone structure.

Vernon’s Greek portico, standing in front of walls inscribed with the names of renowned Western artists, speaks of the European tradition informing the works displayed within the original galleries. Johnson’s glass lantern challenges the primary role that Vernon’s front had in representing the institution to the public, establishing a relationship through contrast. The symmetrical, load-bearing front addresses citizens walking across The Domain from the central city, while the modern, apparently weightless, glass structure projects over its corner, to be appreciated from afar or as one drives along one of Sydney’s major roads. Such an impressive statement is entirely appropriate – the building’s major galleries are not only by the entrance. The AGNSW now has two fronts.

Johnson’s new gallery spaces can also be appreciated as a complement to the existing ones: they add to the different contexts for displaying art. One may pause to study a single object yet will be encouraged to move into other areas. This theme of perambulation goes back to some of the earliest ideas about galleries. For example, G. P. Lomazzo and G. Mancini recommended a decorous arrangement of art, a coherent grouping of genres with an enlivening variety, along a directional passage. Viewing art entailed an enjoyable and edifying consideration of natural beauty, the exemplars of the past, the diversity of humanity and the timeless truths of religious and moral fables. It also involved a long walk, theorists stressing that the health of the mind was linked to that of the body – the art gallery exercised both. Such a formulation enriches our understanding of the AGNSW’s entrance level, where the visitor’s movement, thought and imagination are stimulated by shifting relationships between spaces by Vernon, Andersons and Johnson. Each architect created a distinct setting for viewing art, while also contributing to the circulation areas that connect them.

These linking spaces are initially aligned with the entrance axis, extending from the welcoming portico. The first interior, Vernon’s vestibule, is richly adorned and intimate in scale. For a classicist, these qualities distance the visitor from nature and the bustle of the city, thereby preparing him or her for the building’s next and grandest space. This would be a vaulted hall for people to meet and decide what they would like to see. Such a traditional spatial sequence was only partly relevant to Andersons, because the low ceiling of the galleries that he added to the north continues across the central area, with its information desk. His galleries and this orientation space are only separated by segments of wall. Nonetheless, the idea of an expansive hall is not entirely undermined, as the ceiling stops to provide a double height volume, its axis parallel to, but south of, the entrance one. Filled with light from above and from its glazed wall to the east, this space serves as modern foyer to the Vernon galleries. For Johnson, it also guides the visitor towards his Asian pavilion. He constructed a new path, the visitor walking east, with views directly ahead and to the right. The external walls of the Johnson and Vernon wings frame a splendid urban composition, in which the eye is led from The Domain grass to St Mary’s Cathedral, the central city and sky. Thus, although situated at the south-east corner, Johnson has connected his galleries to the ones of his predecessors through the pivotal role now attributed to Andersons’ brightly lit tall volume.

The Asian pavilion, however, is not the culmination of a single path, as it coexists with two other new spaces to the east – an adjacent function area and restaurant – which form part of a larger circuit extending through the entire entrance level. From the vestibule and information area, the visitor can enter the Vernon and Andersons galleries, or move towards the additions to the east, passing into what is effectively an ambulatory around the escalator shaft. The main circulation, dining and function areas are places where people meet, before or after looking at the objects displayed.

The visitor will appreciate the differences between the various settings for art.

Vernon’s wing comprises a series of top-lit galleries. Excluding distracting noises and sights, the discrete spaces give priority to the viewer and object. An intense relationship is fostered through the embracing walls and ceiling as well as its diffused light. Vernon’s three outer galleries surround two central ones – an ambulatory arrangement.

Movement is therefore valued in a composition based on a room and its suitability to one’s intimate involvement with a painting or sculpture. Andersons’ galleries offer the visitor an alternative way of looking at art. With internal walls positioned in accordance with a free plan, one can walk in multiple directions, through interconnected spaces.

Paintings and sculpture in different locations are seen in a single glance. These works are also connected to views of the harbour and Woolloomooloo. Andersons’ dramatic opening of the AGNSW to the outside was intended to enliven one’s response to art.

Critical of such interplay between art and landscape or the city, Johnson chose to emphasize the views from his restaurant, function area and path leading east from Vernon’s wing. His galleries, however, are hermetically closed, the visitor only aware of nature through the shifting effects of daylight.

These light-suffused spaces are defined by two materials: translucent glass and plasterboard. The milky white glass, seen from the exterior as a lantern, makes walls of light for the interior. Large areas of these walls, however, must be concealed for the protection and display of art. Plasterboard panels form segments of an inner wall and dropped ceilings. Their textured surface absorbs the light that they do not block out. The luminous bright glass walls and warmer plaster surfaces create four outer galleries, each displaying objects from the permanent collection. These spaces surround a dim central one, for temporary exhibitions, its large corner entrances the only source of daylight. Because the space is bland, partly so different kinds of exhibitions can be accommodated, the visitor will be drawn back to the permanent galleries, which are animated by unusual relationships between objects, built form and light.

Johnson was attentive to the framing of a work of art, such as the standing Buddha (c.581–618). With its frontal and static pose, the figure culminates the central axis of the northern gallery. The viewer, however, need not approach the Buddha directly. A delicate but distinctive line of drapery falling from the Buddha’s shoulder, visible on the left, is restated directly behind, in the line demarking the meeting of the bright glass and plasterboard walls. This seam or fold in both the sculpture and architecture has been elaborated as a larger asymmetrical and dynamic composition of walls and ceilings. One is encouraged to move off the axis and study the sculpture from different viewpoints.

Despite examples like this Buddha, the display of art in the permanent galleries is not entirely successful. The proportions of these spaces and the nature of their light may confuse, especially if the visitor is accustomed to the Vernon galleries. Johnson has understood Vernon’s scheme, particularly the way one walks through the three galleries surrounding two central ones. The Asian galleries are also organized to lead one around a central area, the single temporary exhibition space. To help bind the old and new wings, Johnson reiterated the initial thoroughfare. Vernon’s spaces, however, combine two traditional types, a movement corridor and a room embracing a more focused activity. On the other hand, a permanent gallery in the Asian pavilion is too narrow to be a room. This is unfortunate, as the visitor standing quietly to contemplate a work of art may feel out of place, in the way of those using the space as a corridor.

Furthermore, backlighting in the permanent galleries discourages the careful scrutiny of some objects. The plasterboard surfaces are positioned so that gaps appear between walls, ceilings and floor. Thus, the parts of a building that traditionally are solid, often richly moulded, are open to the glass walls of light behind. Intense bands of daylight articulate the edges of a gallery. Broader areas of glass wall are also visible, sometimes behind a sculpture. Art is presented in a novel way, visitors perhaps perceiving a sculpture framed by an aura. Yet this unconventional arrangement can cause museum fatigue. A person’s eyes will adjust to the light source, rather than that on the object to be studied. In the traditional top-lit gallery, light falls over the viewer’s shoulders to illuminate the object that he or she faces. Such a situation, experienced in Vernon’s galleries, may lack drama but glare is reduced to ensure that one’s eyes can see the subtleties of form and colour that characterize the works displayed.

The new Asian galleries, however, are entirely successful when considered in the larger contexts of the building’s historical development and changing ideals of the AGNSW. During the past one hundred years, different gallery spaces have been designed and linked. Johnson’s extension of existing circulation spaces into a circuit means the entire entrance floor now assumes the quality of a landscape. Perambulation is encouraged. While skilfully adding to the interior, Johnson has also created an external form that represents the significance of Asian art to the general public. The glass lantern, which complements Vernon’s porticoed front, encapsulates his design approach.

Formal or spatial solutions from the past are respected when related to new work. As a result, the visitor now has the opportunity to view art in settings devised by three distinguished architects. Each wing of galleries has its own integrity and contributes to one’s appreciation of the entire building.

DR PETER KOHANE IS A SENIOR LECTURER IN ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES.