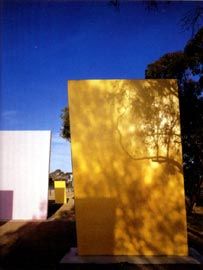

Images: Derek Swalwell

The field of Gold Fragments, by AIA/Burne Hocking Weimar, is stage three of the Images of the West, an initiative of the Western Region Forum. Situated along the Calder Freeway in Melbourne’s west, it consists of a sequence of concrete panels 150 mm thick, in two sizes (1 x 2 metres, 2.5 x 4 metres), 68 of them in total, focused mostly around interchanges with the Tullamarine Freeway and the Western Ring Road. Each panel is painted pink on one side, and gold on the other. The vertical edges are slightly cambered, disguising the fact that making so many things perfectly and permanently vertical was impossible.

Designed to “promote a positive image and provide an identity for this portion of the west”, the project was contrived within very tight budget constraints and did not have the programmatic prompting of sound attenuation which has been the ostensible rationale for a range of other successful freeway projects.

Without the certain but secondary status of being the adornment of utility, AIA/BHW’s project has been driven by a series of references: gold for the old goldfields to the west of the city; pink for the western sunset; the repetition of elements related to the manufacture of objects in western Melbourne’s factories. The panels are robustly made concrete slabs, repeated-but-varying as other elements in the environment of the freeway: signboards, kerbs, off- and on-ramps, bridges, light standards, and houses and factories and power pylons beyond. Rosemary Burne cites less local references as well: the paintings of Jeffrey Smart, the billboard architecture of the Venturi team, land art such as that of Andy Goldsworthy.

While the project might be in part explained through these references, it can only be justified by how it is seen. Pictures of it look fantastic. The coloured concrete panels capture the tracery of shadows cast by the indigenous trees and shrubs of the freeway landscaping, like Barragan’s equally vibrant walls (their published images often feature the shadows of Australian gum trees, so the borrowing here is a debt repaid). The gold glows gorgeously when caught in the headlights of passing cars. Photographs of the project attest to these things. But such kinds of beauty will not normally be apprehended when the panels are seen in situ by passing drivers. The modes of seeing that pertain here are different. Driving on a freeway entails a high degree of concentration on – well – driving. Anything that wants to be seen in this environment has to address a mode of apprehension which is momentary, glancing, and necessarily focused on other things. It is also moving fast.

AIA/BHW’s strategy of a field of objects is appropriate to this mode of seeing. It constructs an appropriate visual scale, which would have otherwise simply have been out of the reach of the budget. Conceptually, there is in fact no limit to the project’s field: more panels could be erected; it could continue to stretch out as the city and the freeway continue to move into Melbourne’s western basalt plains. Nor could any singular gateway or monument as successfully index the attenuated way one condition changes to another in this kind of urban/urbanising condition.

The repetition and variation of the panels allows for a cumulatively developing awareness of the work. Most of those who pass it will do so habitually: commuters going in and out of the city, commercial drivers doing regular runs from one depot or customer to another. It is the way the project has engaged with the habitual and distracted manner in which it will be seen that gives it its strongest architectural quality. Architecture for its users is always background, always noticed indirectly. This necessarily involves the temporal. The project is apprehended as a series of moments, but will also be seen differently at different times of the day and times of the year, differently for example when the grassy banks on which the panels sit are green and when they are tawny. Its character inheres in the ongoing accumulation of these impressions.

The quality of the designer’s achievement is that such variations of what can fleetingly be seen in a stretch of freeway have been so simply activated to make a field of experience.