Every two years, Venice – perhaps the most exotic and architectural of cities – plays host to the Architecture Biennale, during which the world’s architects assemble in the wooded pleasure grounds of the Giardini and the dockyard fortress of the Arsenale.

The Biennale concept, instigated as an art exhibition in Venice in 1895, has been replicated in many places as a cultural exposé, often as an esoteric and irrational arts offering. Rem Koolhaas, the curator of this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale, is to be congratulated for his pursuit of themes of universal relevance and interest, which have at their core the essence of an architectural education. The directness of his message was a welcome change from the usual obfuscation. As George Orwell once said: “To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.”

The full-scale model of Le Corbusier’s Maison Dom-Ino installed in the Giardini by Valentin Bontjes van Beek and students from the Architectural Association.

Image: Peter Bennetts

Koolhaas’s title for the Biennale is Fundamentals and his primary exhibition, Elements of Architecture, explored the evolution of the core building elements. Beyond the darkened central volume of the main pavilion, which showed continuous movie clips that captured “architectural incidents,” each space explained one building facet, such as the history of the window and the contemporary use of glass in this role. A carved marble toilet from the Baths of Caracalla in Rome, on loan from the British Museum, was displayed alongside the development of the water closet, the “S” trap and the latest Japanese “hands-free” toilet. Within a deep door reveal, an array of stylish lever doorhandles were displayed, including examples by Henry van de Velde and Mies van der Rohe. Various stair designs were reproduced, allowing the visitor to try out different flights and appreciate firsthand the contrast between toe-tripping minimum standards and the measured comfort of “easygoing” stairs with generous treads and shallow risers.

The national pavilions explored Koolhaas’s second theme, Absorbing Modernity 1914–2014. It reflected on the erasure of national character and identity in favour of one international language. Has the increasing similarity of all office blocks and airports around the world been a dull and less-than-satisfactory outcome?

Biennale visitors lounge on the Maison Dom-Ino model.

Image: Peter Bennetts

In the centre of the Giardini, a full-scale plywood model of Le Corbusier’s ideal concrete frame – the Maison Dom-Ino – stood proud, a symbol of 1914 new-age construction. An abstract sculpture in which visitors lounged, the model – while true to the diagram – left unconsidered the reality of reinforced concrete and the freely located windows and partitions of Corbusier’s original concept. In Vers Une Architecture (1923), Le Corbusier extolled the virtues of “the ‘House-Machine,’ the mass-production house, healthy (and morally so too) and beautiful … Beautiful also with all the animation that the artist’s sensibility can add to severe and pure functioning elements.”1 His vision of unadorned concrete buildings in park settings dominated postwar building and reconstruction in the 1950s. The houses that resulted satisfied an urgent social agenda for new, basic housing for the masses, but generally lacked an artistic dimension. Multistorey blocks of pared-back apartments superseded the urban terrace house, with the visible materials – concrete, metal and glass – chosen for their low maintenance. Clean and new, the buildings sparkled. The British and French exhibits clearly demonstrated the failure of these bold experiments: today, these buildings are typically drab and decaying, host to depressed social environments.

By way of contrast, the Brazilian pavilion was full of modernist joy from the 1950s through to the 1980s. Vigorous and fresh, the architecture clearly responded to the tropical climate, with generous verandas and living spaces, giant brise-soleil and colourful wall murals. The lively images gave heart to the possibilities of more individually expressive modern architecture.

Australia’s showing this year was unusual, as the pavilion is in the throes of being rebuilt. A generous orange canopy called Cloud Space “floated” above a platform in the Giardini, sheltering an intriguing display, experienced via a mobile phone app, of what might have been: heroic unbuilt architectural designs for Australia from the last one hundred years. Re-created as three-dimensional objects, one could tour around and sometimes within these structures – a marvel of realization through modern technology.

Pier Luigi Nervi, Antonio Nervi, Carlo Vannoni and Francesco Vacchini, Cathedral, Abbey and Benedictine Monastery, 1958, New Norcia, Western Australia, Australia. Digital reconstruction by Matt Delroy-Carr, Keith Reid, Scott Horsburgh.

Image: felix

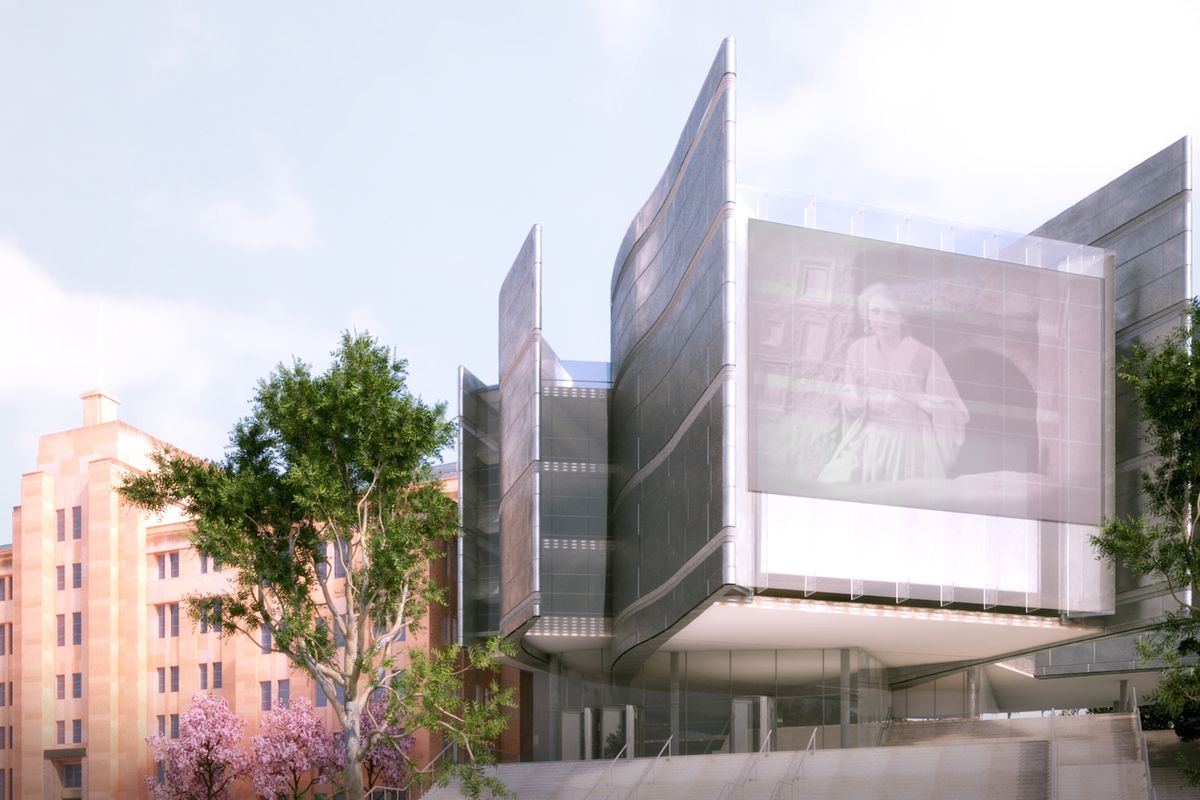

Included in Augmented Australia 1914–2014 were the Griffins’ temple-like hilltop Capitol for Canberra (1914); Harry Seidler’s 1952 scheme for the Melbourne Olympic Stadium, with a distinctive cable-stayed canopy; Pier Luigi Nervi’s vaulted Cathedral, Abbey and Benedictine Monastery planned in 1958 for New Norcia north of Perth; and the fluid Francis-Jones Morehen Thorp scheme to extend Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art from 2001. The remarkable 3D resolution of the chosen schemes, combined with the supporting research and critical commentaries – all “floating through the ether” in Venice – represented a logistical and technical triumph.

Like much of contemporary Western society, the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale embraced the past and celebrated the present. Unlike Le Corbusier’s vision in the early twentieth century, however, it gave few overt clues to a better future in which the world might improve through practical, stylish and more equitable architecture. In this age of commercial outcomes, what has become of governments’ once significant commitment to the public realm through a better built environment?

Note: Howard Tanner is a supporter of Australia’s participation in the Venice Architecture Biennale.

Australia’s creative team for Augmented Australia 1914–2014 comprised Rene van Meeuwen, Matt Delroy-Carr, Craig McCormack and Romesh Goonewardene of felix., Sophie Giles of Giles Smith Architects, Professor Simon Anderson from the University of Western Australia, and Professor Philip Goad from the University of Melbourne.

1 Towards a New Architecture, The Architectural Press (England: 1976), 210.