When I graduated in the late 1990s as the first Indigenous woman from Queensland to complete an architecture degree, the pace of Indigenous recognition in Australia seemed slow in comparison to international shifts. Renzo Piano Building Workshop had recently completed the Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Center in New Caledonia (1998) and, at the time, Indigeneity in architecture was only contemplated as a fringe experience, riding a new wave of commodifying difference in cultural tourism. After Tjibaou, the shift from fringe to hyper-scaled centre began, moving us towards an inclusive future in which Indigenous rights in land and design were made possible. In Australia, Brambuk – the National Park and Cultural Centre in Victoria’s Grampians National Park – was struggling to meet the needs of state visitors on shoestring funding, but there were few opportunities to experience Indigenous cultures through the medium of architecture in urban centres. Indigenous culture and its more exotic features were easily marketable at remote sites such as Kuniya and Liru/Uluru-Kata Tjuta, but the vexed history of colonization was hotly avoided.

That was until 2001, when the National Museum of Australia unsettled the complacency by opening the First Australians Gallery and Garden of Australian Dreams. Still, the architects of buildings such as Brambuk – although sensitive to truths about our national identity – were not Indigenous. In 2004, the National Museum of the American Indian opened in Washington, DC, designed by Blackfoot architect Douglas Cardinal. Concurrently, Australia’s first Indigenous-led design unit, Merrima Design Group, was finding its stride. These were early steps toward Indigenous recognition, without a clear indication of whether these shifts would have ongoing momentum or be subsumed by competing agendas. So it was unimaginable that, a decade and a half later, architects would be advocating for Indigenous sovereign rights to land and seriously contemplating the implications for the planning and design sectors. At the Australian Institute of Architects’ 2019 National Architecture Conference, Collective Agency, there was a call for architecture to reconfigure its relationship with Indigenous knowledge, not only by necessity but also as a means of enriching the built environment. Indigeneity is now firmly on the agenda.

Garden of Australian Dreams at the National Museum of Australia.

Image: National Museum of Australia.

Today, it is increasingly common to find architectural writers and practitioners attentive to the legacies of colonized space. Some have gone further and advocated unsettling the colonial past with ambitions to decolonize the settler city. The practices of colonial expansionism, displaced sovereignty, mass migration, enslaved labour, extraction economies and global industrialization are recognized as forces that have shaped free markets and consumptive capitalism. Some advocates seek to expose how colonial nation- building enshrined unequal power through architecture. Uncovering the hidden histories embedded in built form has sparked new dialogues with its artefacts. Badtjala artist Fiona Foley curated the 2014 exhibition Courting Blakness: Recalibrating Knowledge in the Sandstone University (2014); located in the University of Queensland’s Great Court, it showed how art and architecture could strike new readings of old depictions of history and race. 1 Another recent example is the American Indian Center of Chicago’s collaboration with activist collective the Settler Colonial City Project for the 2019 Chicago Architecture Biennial. Their exhibition, Decolonizing the Chicago Cultural Center, offered alternate readings of the appropriation of Sioux and Navajo motifs in the cultural centre’s building. It involved installing plaques around the cultural centre to highlight the building’s complicity in colonial violence, exploitative labour, stolen land and appropriated iconography. These projects were not so much about undoing the making of architecture but, rather, challenging conventional views about how architecture was made and the stories it told.

In his article “Re-imagining a museum of our First Nations,” Kieran Wong of The Fulcrum Agency considers how Australian institutions could better portray difference. While practices of classifying Indigenous peoples as ethnographic and biometric curiosities may now be outdated, including Indigenous voices is still an emerging practice norm. It prompted his question, “Could the museum of the future be an enabling space, culturally dynamic and future focused, rather than categorizing First Nations culture as a relic of our Colonial- Settler past?”2 Dynamic cultural representation is not only embedded in Indigenous ownership and agency, but is also central to future aspirations of becoming connected to a living culture that extends beyond imagery and branding.

Quandamooka Art, Museum and Performance Institute by Cox Architecture.

Image: QYAC

The ways in which Indigenous voice and agency are included in building procurement must be strategically considered to ensure that any proposed solutions meet real, not imagined, design requirements. A recent article by Timothy O’Rourke and Daphne Nash on the design of hospitals demonstrates how the intentions of inclusive design can go awry.3 The article highlights that solutions calling for separate waiting areas in hospitals for Indigenous patients are clearly disturbing because they unintentionally hark back to the era of segregation. The authors observe that there is little evidence that redesigning hospital waiting rooms would enhance the needs of Indigenous patients and their carers. It is vital to ensure that, across varied institutional settings, legitimate demands for cultural recognition are not advanced under dubious frameworks that might effectively misdirect meagre resources and create “solutions” destined to become future problems.

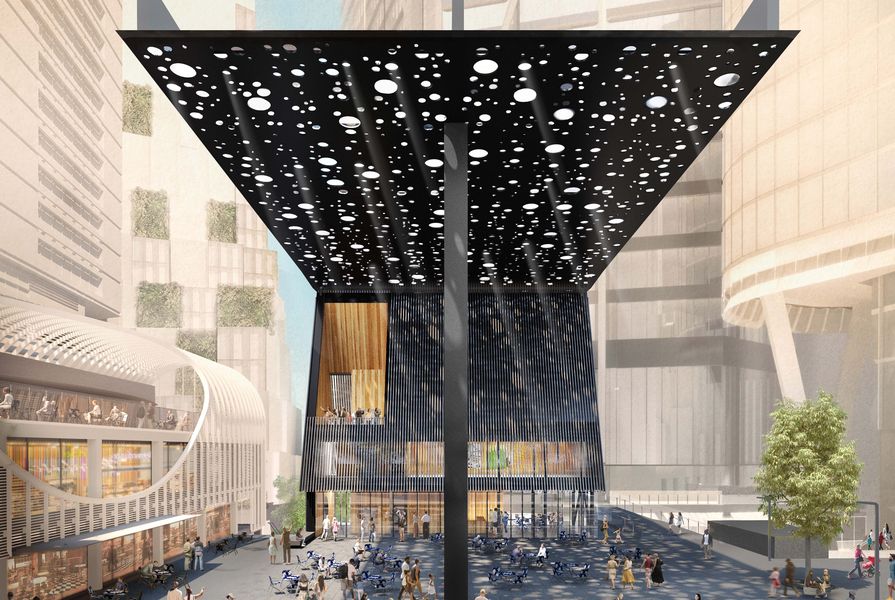

New modes of imagining culturally inspired forms demand collaboration in design in order to create opportunities for unspoken narratives to emerge. Indigenous designers universally advocate for higher levels of Indigenous agency and authorship. In countries where Indigenous people are decided minorities, and where there are miniscule numbers of Indigenous architectural practitioners, this presents ongoing challenges. However, collaborations can explore synergies between architecture and Indigenous artists. Adjaye Associates’ partnership with Dyirbal artist Daniel Boyd on a new building and public square planned for Sydney’s Circular Quay precinct will tell a single story out of innumerable colonizing stories of Australia. It places the Gadigal people of Eora nation and their lands at the centre of civic space. David Adjaye and Daniel Boyd’s vision deliberately plays to Sydney’s sovereign origins and its cultural hyper-diversity. The collaboration opens a new dialogue about place history and its presence in reframing civic space.

The proposed plaza and building on Sydney’s George Street designed by David Adjaye and Daniel Boyd.

Image: Adjaye Associates

Making matters of social importance visible is on the rise in major architectural exhibitions and conferences, with calls for self-reflection and vanguard action inspiring and dividing audiences in equal measure. Think back to the response to Alejandro Aravena’s treatise of global responsibility for the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale, Reporting from the Front. Advocating for a more humane architecture – one that is crisis-responsive, locally contextualized and characterized by a humbler palette – raised the ire of some critics for its disservice to the core concerns of architecture. Aravena’s focus on pressing global issues gathered a body of activist architects ingeniously working on community participatory design in fringe locations from across 37 countries. Notably, to an Australian audience at least, without a single contributing Australasian practice. The exclusion wounded many local architects’ perceptions of their global relevance, but the slight turned into an opportunity to run away with Aravena’s thesis. The dossier in Architecture Australia’s September/ October 2016 issue entitled Reporting from the (Australian) front: Housing in extremis, guest edited by Naomi Stead and Kelly Greenop, featured a series of articles attentive to our own problem frontier of housing insecurity, each requiring solutions to ongoing vulnerabilities within our own borders.

The dossier in this issue addresses Australia’s absence from the 2019 Chicago Architecture Biennial. Under artistic director Yesomi Umolu, the theme “… and other such stories” inspired a compelling probe of Chicago’s and other cities’ colonial spatial legacies. Without labouring over why Australia is the wallflower of the architectural world, there is value in querying how we show up on the international stage in matters of Indigeneity and how we are tackling our own spatial legacies. What do our shared experiences around land and water sovereignty, and their intersection with the built environment, say about our future visions for Australian place? Could such an examination open a new way of valuing Indigenous sovereignty, narratives and histories and, at the same time, reshape architecture?

While asking these questions of Australia, it is apparent that many of the same challenges are faced by Indigenous people elsewhere. We share the tainted history of colonialism with other Indigenous nations across the Pacific, namely Canada and the United States. Hence,the four Indigenous contributors to this dossier include two local practitioners and two from across the Pacific. They were prompted to draw inspiration from one of Umolu’s four thematic provocations (“Rights and reclamations”), which sought to “interpret space – urban, territorial, environmental – as a site of advocacy and civic participation, investigating spatial practices that foreground the rights of humans and nature.” Launching off this inspirational springboard, the four essays centre on broad topics related to design sovereignty and voice in architecture. The creative activities considered are in many ways an addendum to architecture, but they are worthy of appreciation and representative of small beginnings that will keep growing.

Saddle Lake Cree Nation architect Wanda Dalla Costa begins by talking about how cities, towns and the spaces we inhabit are populated by diverse peoples, many of whom are under-represented in architecture. Dalla Costa discusses two projects in urban centres in the USA and Canada that take a culturally-centred approach to design and are locally responsive to place histories, social imperatives and aesthetic representation.

David Fortin, a member of the Métis Nation of Ontario, reflects on the acclaimed Canadian exhibition for the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale entitled Unceded, providing insight into how Indigenous peoples navigate representation of diverse cultures from varied landscapes, places and communities. Rather than collapsing territories and peoples into a singular entity under the umbrella of architecture, the collaborators took a regional storytelling approach based around four broad themes (“territories”). Unceded did not shy away from the destructive and overt practices of colonial social engineering and its ongoing repercussions in land, design, social and health inequalities.

Sarah Lynn Rees contemplates the highs and lows of the Blakitecture talks series on the MPavilion program in Victoria. The platform for Indigenous dialogue stemmed initially from 2017 MPavilion architect Rem Koolhaas’s agitations for an alternative concept of “countryside.” The two-hour time frame of that one-off event proved to be wholly inadequate for addressing so many Indigenous perspectives, and Blakitecture is now a regular and well attended series.

The final essay, by Kevin O’Brien, explores the adaptive travelling theatre Blak Box, produced in collaboration with curator Daniel Browning and lighting designer Karen Norris. The project takes visitors on an immersive experience of Indigenous concepts of Country, exploring land and sea sovereignty through spoken word, sound and form. The lighting design simulates the changing conditions of daylight at dusk, sunset and evening, while the tactile engagement of visitors’ feet with the ground forges a connection to Country.

This dossier spotlights how the future of Indigeneity is made possible now that Indigenous practitioners are pursuing Indigeneity in architecture through different avenues, illustrating how approaches to design, agency and voice can give importance to Indigenous culture and its diversity. This can be achieved through collaborations, by responding to stories, and by exposing histories that are place-based, but not necessarily always place-specific. Many Australian architects have already responded to culturally reflective design challenges and are actively recalibrating how architecture is designed, deployed and discussed. It is heartening to see the rise of exemplary processes and fruitful collaboration undertaken by prominent developers and architects that have engaged the knowledge and skills of Indigenous makers, designers, artists, workers and businesses. The impetus must continue as we collectively reshape our design future.

1. Fiona Foley, Louise Martin-Chew and Fiona Nicoll (eds), (2015) Courting Blakness: Recalibrating knowledge in the Sandstone University (St Lucia: UQP).

2. Kieran Wong, “Re-imagining a museum of our First Nations,” The Conversation, 18 November 2019, theconversation.com/re-imagining-a-museum-of-our-first-nations-123365 (accessed 15 January 2020).

3. Timothy O’Rourke and Daphne Nash, “Making space: How designing hospitals for Indigenous people might benefit everyone,” The Conversation, 5 December 2019, theconversation.com/making-space-how-designing-hospitals-for-indigenous-people-might-benefit-everyone-122550 (accessed 15 January 2020).

Source

Discussion

Published online: 26 May 2020

Words:

Carroll Go-Sam

Images:

Adjaye Associates,

National Museum of Australia.,

QYAC

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2020