It’s unnerving coming face-to-face with a house that’s almost the same age as you are, especially when you are there to review its longevity as a significant piece of Modernism. I can’t help comparing how it and I have stood the test of time. Radical changes in domestic life have taken place since it was completed more than fifty years ago, and yet some things remain constants. This house was designed for the Ghillanyi family of four in 1957 and is the only extant Seidler house in Adelaide. Visiting the house is an undeniably nostalgic experience – not just for this woman of a certain parallel age, but also probably for the many architects who viewed it during recent open inspections while it was listed on the real estate market.

There is something poignant about looking at what was a brave new work in its time, a design full of optimism and challenge to the conventions of Australian architecture and suburban residential models. Set in the leafy suburb of Beaumont, this house was in the vanguard of contemporary projects built across the foothills in the late 1950s and early 60s by small-l liberals. These modest cultural mavericks were drawn to the native landscape of the comparatively undeveloped area and the chance to develop a more regional and relaxed way of life.

Throughout the house, Seidler’s durable built-in furniture adds clarity, utility and detail to the precisely planned spaces. Artwork (L–R): Judy Watson; Barbara Weir.

Image: David Sievers

The surroundings may have become more densely built, but the sense of connection to the environment and essential fit with family life remains. The current owners – the third owners in the house’s history – are reluctantly leaving “a home that has been incredibly easy to live in” for a posting in Prague, quipping that they have found an Adolf Loos house there that might go some way as a replacement. The ten years they have spent in the house comes across as a respectful and robust conversation, in which they have sought to understand and enhance the original identity of the house, while finding ways to adapt its spaces and services to current standards.

Apart from the owners’ awareness of the house’s contemporary heritage and aesthetics (gleaned from professions allied to the arts and theatre), they have been periodically advised by architect friends Nicolette di Lernia and Michael Queale. The balance is one of sensitive renewal rather than pedantic restoration, the logic being that one of the tenets of Modernism was that a building should respond to its time and embrace current technologies. “After all,” Nicolette stressed, “you’re not living in a museum.”

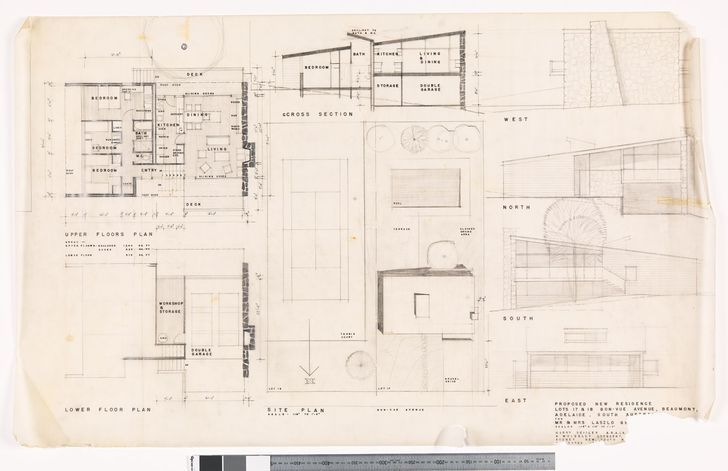

Harry Seidler’s original drawings of the Ghillanyi House (1957-1959). Image: State Library of NSW - PXD 613/51.

This house, however, has provenance. The owners have gathered information from the University of South Australia Architecture Museum to compile a comprehensive record of its history, confirming everything from its cost (£8136) to its date of completion (July 1959). Exploring the documentation, I discover a happy synergy. The construction of the house was supervised by Dickson and Platten – Adelaide’s pre-eminent practice of the time, my first architectural employer and a subject of my research since I became an academic.

It should be no surprise, as Dickson and Platten was effectively the South Australian equivalent of Seidler, approaching its projects from first principles, with a similar lack of pretension, and with acute attention to craft and materiality. The letters exchanged between the practices make interesting reading, their measured tone contrasting with the plain patter of twenty-first-century email:

Newell Platten: “The northern pine tree is in exactly the right position – one long bough sweeps low across the brickwork, toward the entrance in a symbolic greeting.”

Harry Seidler: “I am very pleased about the position of the tree.”

Consistently, Seidler’s instructions are toward simplicity and functional a-stylism: junctions are to be “the neatest and cleanest” achievable, and fittings of “clean and simple design.” Though his preferred materials were diverse in texture – random rubble, smooth face brick, off-form concrete – the overall palette was comparatively pale and subdued, in contrast with contemporaneous international works by the Eameses, Alvar Aalto or Richard Neutra. Dickson and Platten was fastidious in sourcing materials to satisfy Seidler’s subtly antipodean version of the cool white box of Modernism – pale bisque, cool grey-green and wheat-coloured stone. They must have interpreted his directions accurately, for in one of the last letters Seidler is almost effusive:

“The place appears to be quite up to our standards.”

Yet it seems he never visited the house personally, probably because its construction coincided with a rapid expansion of his practice into the multiresidential and commercial sectors, and substantial projects like Sydney’s Australia Square that furthered his authority in Australian architecture.

Both the private and public zones of the house are finely tuned to orientation and access to the outdoors.

Image: David Sievers

The Ghillanyi House is now more vibrant in tone than Seidler’s original scheme, with some bravura use of colour in painted feature walls, primary hues for curtains in each child’s bedroom and abstract external murals. It is also more expansive in accommodation: the incorporation of an additional bedroom and bathroom has liberated the original main bedroom for a children’s rumpus room, in keeping with the current fashion for discrete parent/child living spaces. The fundamental plan nevertheless remains the same (aside from the infill of the double garage, which became the main bedroom), with distinct public and private zones, each finely tuned to orientation and access to the outdoors.

Surprisingly for a house of this vintage, the “dormitory” wing of bedrooms is as proportionally generous as the shared living spaces. Throughout the house, Seidler’s durable built-in furniture adds clarity, utility and unexpected detail to the precisely planned spaces. In the living room a suspended silver ash cabinet bears his signature recessed uplighting. Vivid colour-backed glass doors have been retained and restored, and are referenced by the new glass splashback (originally tiled) and joinery in the kitchen – the effect is empathetic and enlivening.

The most alteration has taken place in the kitchen, as perhaps befits the most technologically driven space of the home. Caesarstone has replaced white laminate, charcoal ceramic tile the perished vinyl floor. The work triangle of stove-sink-refrigerator has been flipped to accommodate today’s larger appliances, and more critically to reposition the heat source away from the major traffic path.

Although the surroundings have become more densely built, the sense of connection to the environment remains.

Image: David Sievers

With its substantial overhangs and thermally responsive materials, the house is a built textbook of passive climate control. During my visit, a typical Adelaide scorcher plateaus before a late-afternoon change. The living room curtains are thrown back, the massive doors at each end are slid back, and within moments the space is refreshed with a gully breeze. The owners have only recently installed airconditioning – an elaborate task in itself as the exposed structure and assemblage of the building leaves nowhere to hide services.

The bones of structure and construction are right too. I count only one and a half modest cracks anywhere – remarkable for Adelaide’s notoriously reactive terroir. Living in a renovated Edwardian villa, I had convinced myself cracks are a sign of character in a house – like wrinkles on a gracefully ageing person. But in the face of Seidler’s smooth platonic planes, I confront my disingenuousness – about ageless houses at least, if not skin.

Overall, the Ghillanyi House has impressive volumetric composition – or as one eleven-year-old occupant affectionately says, “we live in the house that looks like a block of cheese.” With pared-back detailing where it counts and its architectonic landscape, it reminds me of my first architectural graphics primer – all strong shapes, distinctive foliage and high-contrast light and shade. Yet this singular place has developed a patina; it does show signs of wear and tear and adaptation. Have I weathered the last half-century as well? Have I maintained my character with as much serenity and surety?

This design was part of a manifesto. Looking around this now dense, affluent suburb, with its pleasantly bloated mansions and chameleon stylism (part Tuscan palazzo, part Balinese resort), I wonder how successfully Seidler altered our architectural pretensions when it comes to suburbia. Perhaps the Ghillanyi House only went some way to achieving that aspiration, but I suspect it went much further with an equally lofty aim – to make an avant-garde house that feels like home.

This review is part of the Houses Revisited series.

Credits

- Project

- Ghillanyi House

- Architect

- Harry Seidler and Associates

Sydney, NSW, Australia

- Site Details

-

Location

Adelaide,

SA,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Type New houses

Source

Project

Published online: 11 Aug 2014

Words:

Rachel Hurst

Images:

David Sievers

Issue

Houses, April 2014