I have to begin with a confession. Prior to my site visit to the Gissing House to write this article, I wasn’t even aware of its existence. The Gissing House was introduced to me as a smaller, more modest and compact 1972 iteration of Penelope and Harry Seidler’s own house in Killara completed in 1967 (revistied for HOUSES 81). Given the esteem in which I hold the Seidler House, this was a pretty big hole in my scholarship of modernist projects in Sydney.

I first visited the Seidler House in Killara in 2005 on an architectural tour led by the Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales. I was immediately struck by the spatial complexity created by the split-level section within an orthogonal, gridded thick plan form, and the directness with which this organizational strategy was expressed in the eastern elevation of the house. It was the most monumental and assured elevation I had ever seen in a domestic setting – a huge, sloping cantilevered concrete upturn beam floating over two concrete terraces linked by a switchback stair which became sculptural through the simple act of administering the level change of the terraces.

I concluded that this private, secluded house in a bushland setting was part of a fascinating global dialogue of late modernism. Like the late modernist works of Paulo Mendes Da Rocha or Joao Vilanova Artigas in the late 1960s and 1970s in Brazil, this dialogue highlighted a particular tension between northern hemisphere and southern hemisphere modernism in terms of origin and originality. If many of the ideas for these works had their origins in the northern hemisphere works of Le Corbusier, or in Seidler’s case the work of Marcel Breuer, they found their most natural application in the subtropical landscapes and benign climates of Sao Paolo and Sydney. In my view these works were not southern imitations of northern disciples, but inventive and intensified realizations of the late modern project made possible by the diverse geographies of the south.

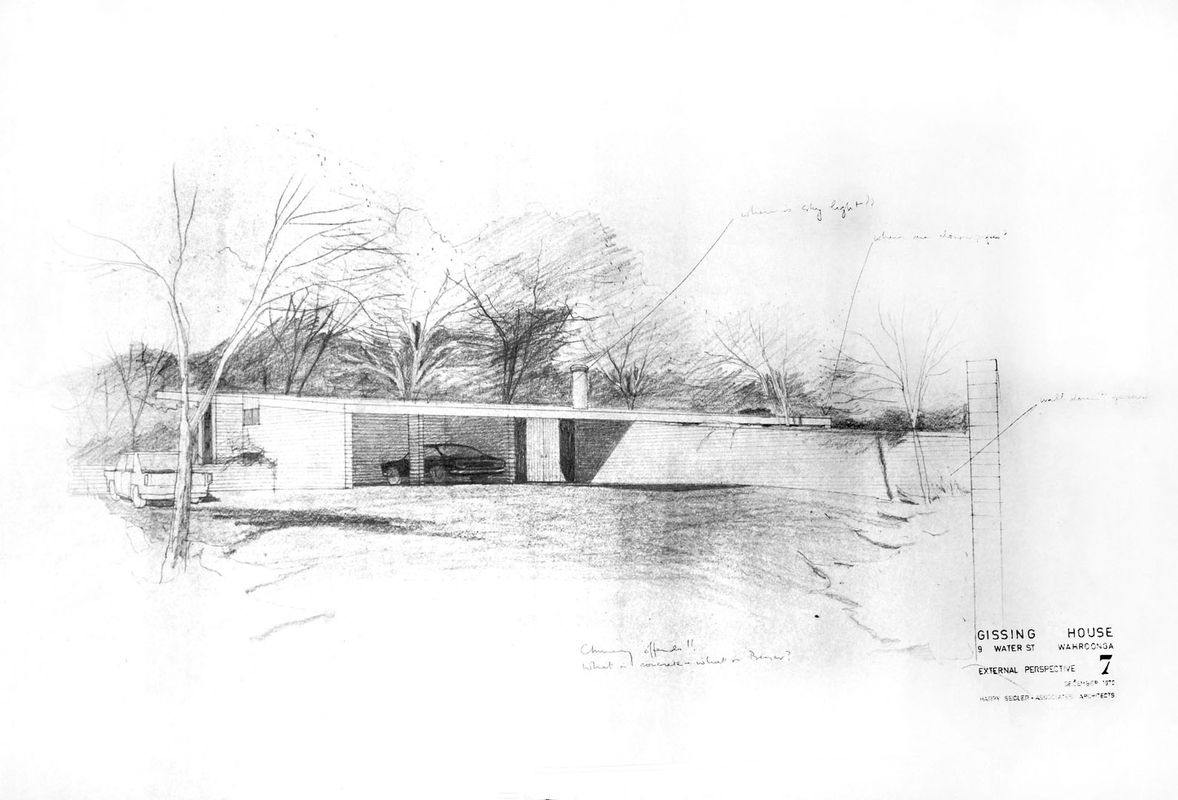

To discover a close iteration of a work as important as the Seidler House in the architectural landscape of late modernism in such unchanged, authentic condition was a revelation. Apparently John and Janet Gissing (Janet was an old friend of Penelope Seidler’s) were at dinner at the Seidlers’ Killara house and were so impressed they asked Seidler to design a house “just like [his] own.” But the circumstances of the commission would make the Gissings’ version more sibling than twin – the design would have to adapt to a more modest budget and to a tighter, more compact suburban battleaxe block with north at the front entry of the site.

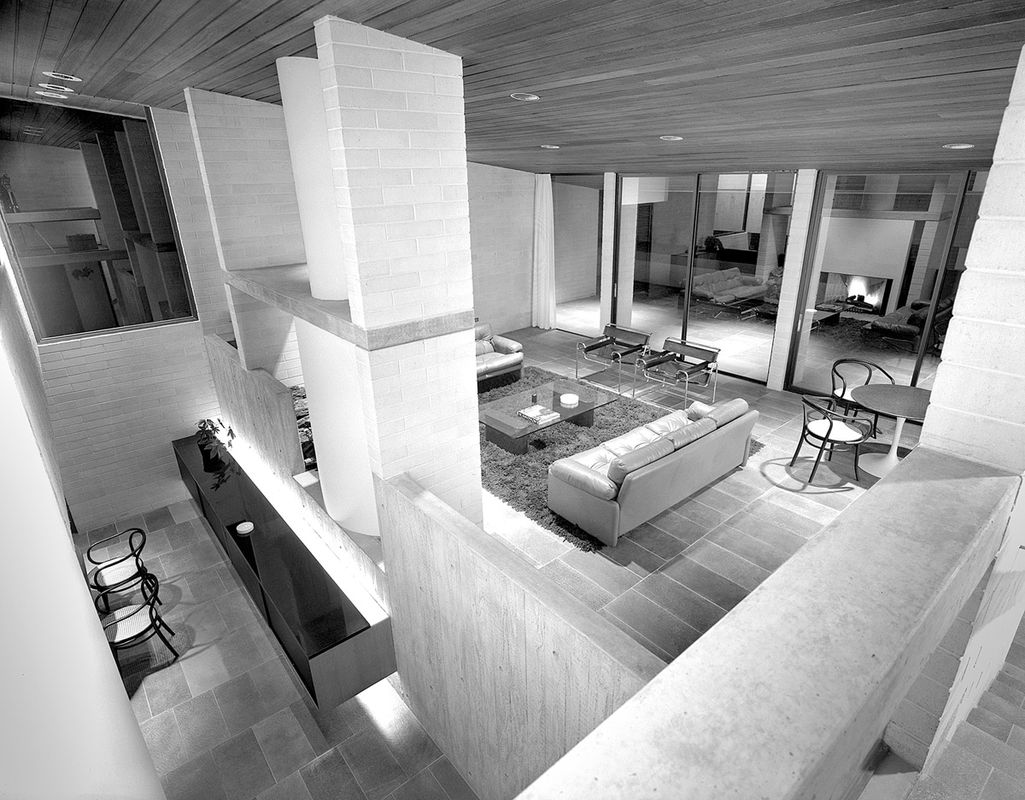

Circulation is structured around an articulated double-height void.

Image: Max Dupain

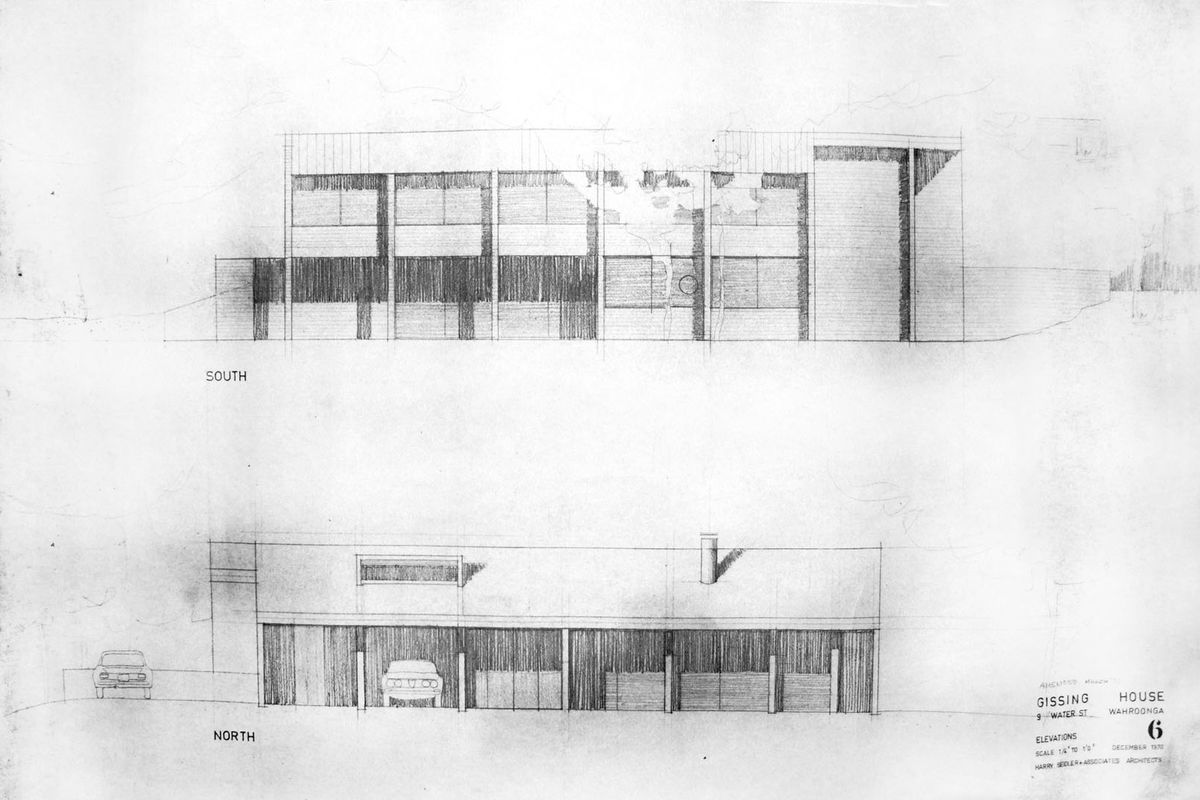

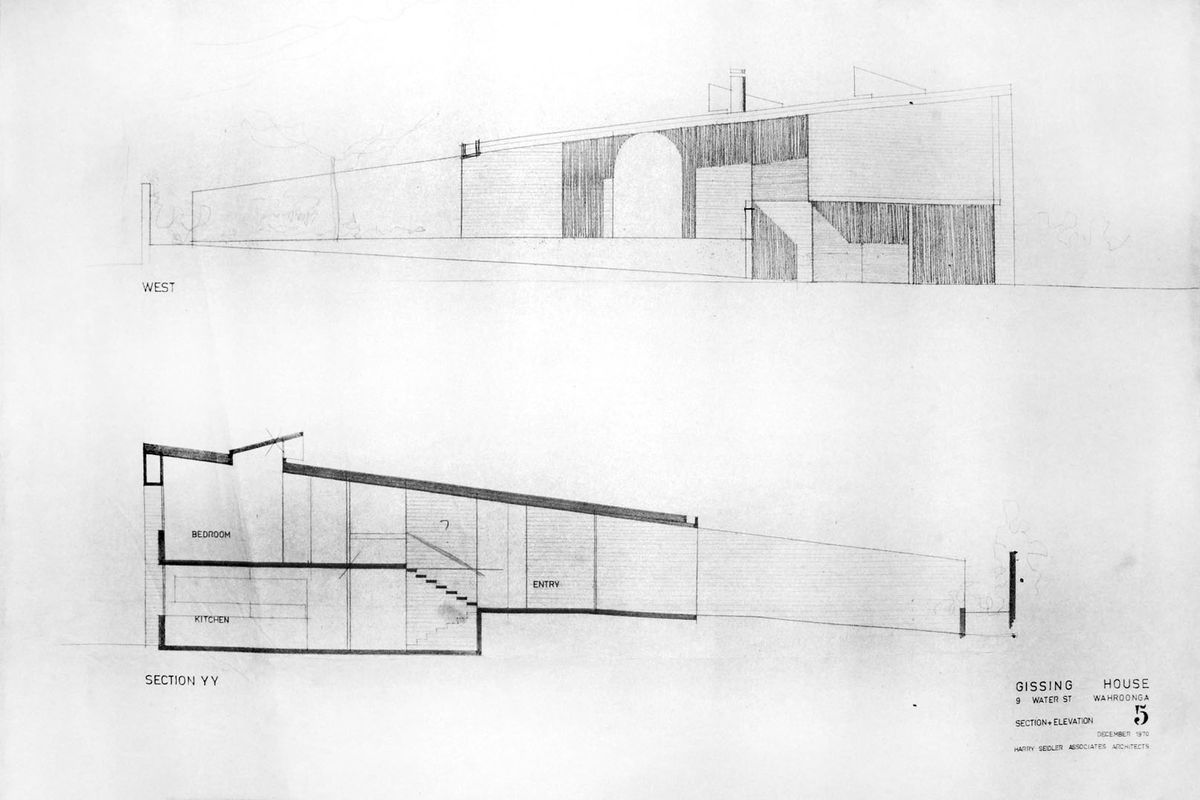

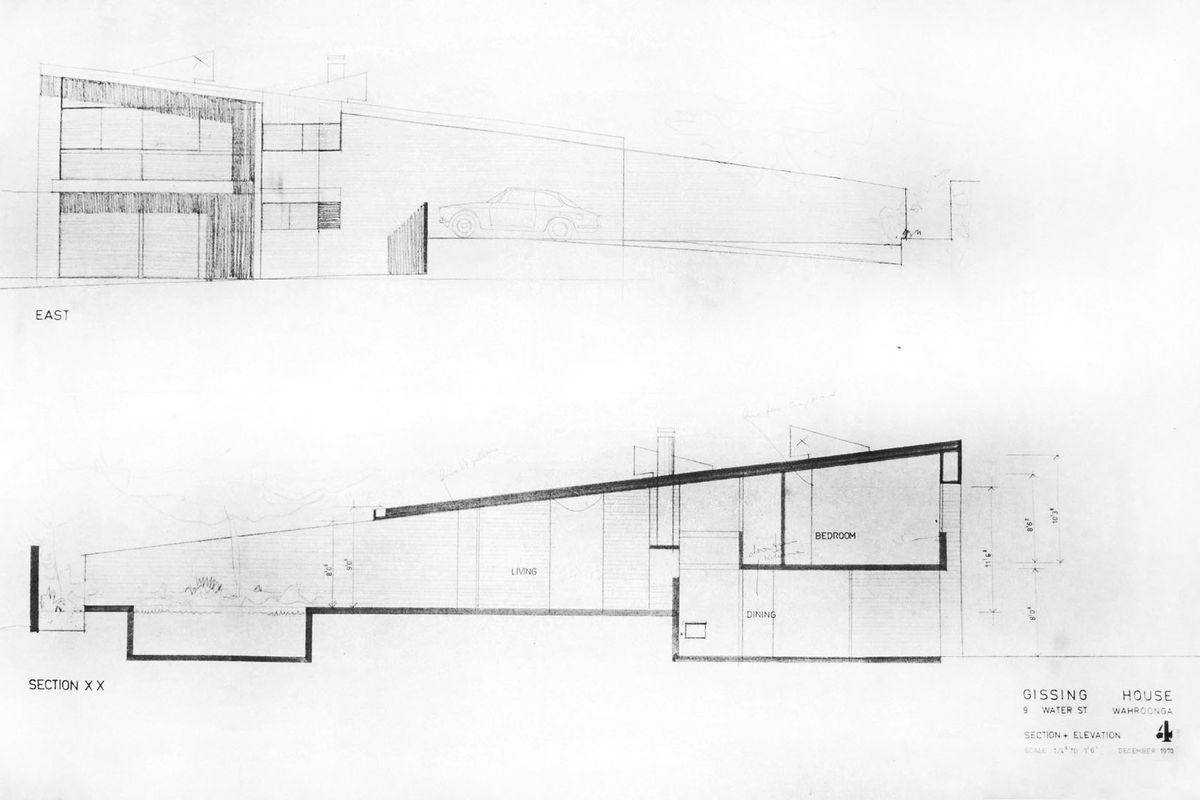

The Gissing House uses the strategy of the split level on a sloping site to organize three levels of program: an upper level containing a main bedroom, three children’s bedrooms, a bathroom and a guest bedroom; a lower level containing a laundry, a family room and terrace, a kitchen with an informal eating bay, and a dining room and terrace; and a mid level which contains the garage, house entry, a small coat bay and toilet, and a living room opening onto a terrace and pool area. The house has almost as many rooms as the Seidler House but in a much smaller overall footprint.

The white concrete block was prototyped exclusively for the house.

Image: Max Dupain

The organization of the program in plan is through a series of north–south blockwork walls. These walls are the dominant architectural element shaping the spatial organization of the upper- and mid-level plan, and the building’s entry from the battleaxe laneway. Organized on the dimension of a white concrete block prototyped exclusively for the house (fears that it would lose its colour stopped it from going into mass production; today the colour remains in perfect condition), one of the most interesting aspects of the house is how these walls, so disciplined in their east–west grid, are varied in their north–south length to such striking spatial and organizational effect.

One example of this is how the wall extending from the middle of the six-bay grid projects north outside the building for the full extent of the site to separate the living room terrace and pool area from the entry and garage courtyard. In this single move Seidler resolves the basic flaw in any battleaxe block entered from the north, allowing the living room to open to a private and discrete “rear” north-facing yard at the front of the block.

A wall projects outside the building separating the pool area from the entry.

Image: Chris Colls

The use of the internal walls to extend and organize the site planning of the block is also evident in the lower-level plan. Here a series of east–west walls provides a retaining function, creating the topographic organization of the site on which the split-level interior is based. These east–west walls also allow specific rooms in the house, such as the kitchen, dining and family rooms, to reorientate away from the north to other views of the garden landscape. This creates a “pinwheel” plan, with the house occupying the centre of the site and creating a series of walls extending from the centre to the edge of the site to set up multiple viewing lines of a picturesque garden wrapping the periphery.

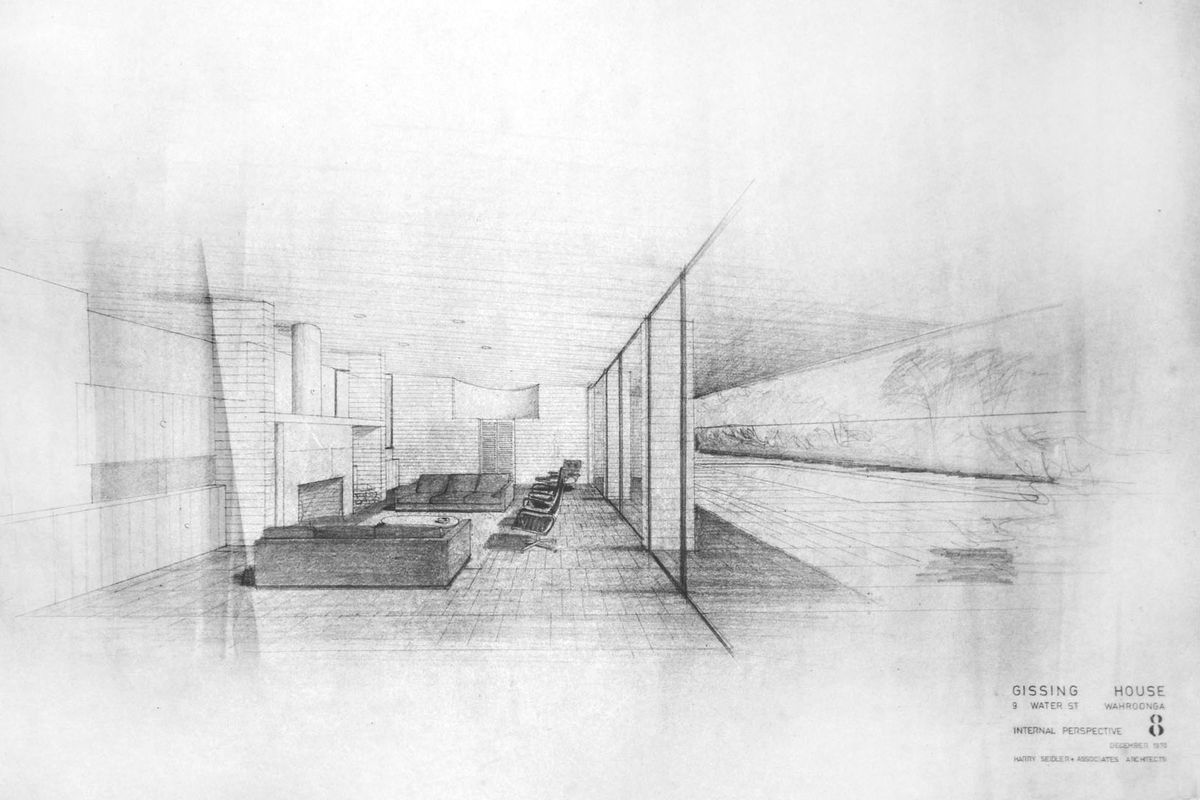

One of the most satisfying aspects of the Gissing House interior is the compactness of the plan organization in combination with the spatial quality of the split-level section. This quality is a result of the simplicity of the circulation structured around an articulated double-height void through the centre of the house at the point of the terraced section. This organizing element, transferred from the Seidler House in Killara, takes on greater intensity and effect within the more compact dimensions of the Gissing House.

The split-level section enhanced by the light and outlook of a large window.

Image: Chris Colls

The circulation of the lower level is within the void of this split-level section, and is shaped by the light and outlook of the generous window carefully composed from the base of the upper-level structure to the ceiling above at the end of this spine. The upper-level circulation is accessed from the split-level stair and a bridge over the void that aligns with the entry, followed by an east–west passage offset from the full-height void, which links the five upper-level rooms. With generous openings back through the void to the living room on the mid level, it is remarkable how effortlessly this spine serves so many rooms without complicating the split-level organizational structure. As a result the circulation at the Gissing House feels invisible and natural.

In short, the house is very uncomplicated in its organization but rich in its spatial experience. Sitting in the living room looking towards the fireplace, one experiences a simultaneity of viewpoints – the ground covering of the garden through the lower doors of the dining room, and the sky and high trees through the upper-level bedroom windows revealed through an opening in the upper-level hall, all framed by the layered and materially distinct interior thresholds.

The material palette of the house is as logical as it is beautiful. All the east–west retaining walls and all bridging and spanning elements are in a rough-sawn timber formed from in-situ concrete, including the underside of the slab that forms the ceiling to the lower level dining room, kitchen and family room. All secondary structural walls, primarily running north–south on the upper levels and east-west on the lower level, are in the white concrete block. This forms the basic material palette of both the interior and the exterior. Added to the interior are infill masonry walls to provide additional screening and privacy for the bedrooms and other minor rooms, finished in a white render. Like the Seidler House, the ceiling, and much of the joinery and cabinetry, are in a stained Tasmanian oak, and the floor in a carefully set out quartzite tile.

The fireplace. Artwork: Dorothea Reese-Heim, Baum, 1973.

Image: Chris Colls

If a single element exemplifies the richness of the Gissing interior, it is the fireplace. Located within the central bay of the three ten-foot bays that structure the living room, and sitting on the edge of the split-level terrace, it captures and miniaturizes the spatial and material composition of the house. From all three levels of the house it becomes a locus, providing a screen that moderates the openness of the two-storey central void, and a frame that controls and animates how the different levels of the house view each other and the landscape beyond.

If the Gissing House was a more modest sibling of Seidler’s own house, it was clearly no less loved. The project was painstakingly detailed, with extremely thorough working drawings neatly tucked away in one of Seidler’s signature floating cabinetry pieces in the living room. Its original owner and subsequent owners have maintained the house carefully, and all the original furniture and artworks selected for the house are still in place.

The Gissing House is a compact but beautifully executed work that offers a more modest voice in the conversation of late modernism. And it is perhaps a transitional work in the body of Seidler houses, with the subtle introduction of the semi-circle in peripheral elements of the house a hint of what was to come.

This review of the Gissing House is part of the HOUSES Revisited series.

Credits

- Project

- Gissing House

- Architect

- Harry Seidler and Associates

Sydney, NSW, Australia

- Site Details

-

Location

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

Site type Suburban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Type New houses

Source

Project

Published online: 31 May 2013

Words:

Andrew Burges

Images:

Chris Colls,

Max Dupain

Issue

Houses, April 2013