SUMMARY OF MAJOR FINDINGS

GOING PLACES: CAREER PROGRESSION OF WOMEN IN THE ARCHITECTURAL PROFESSION

How do women fare in architecture? Going Places, Paula Whitman’s survey on women’s career progression in the profession, frames the issues and outlines a series of recommendations. Architecture Australia asked a range of women – of different ages, locations and practice backgrounds – to respond to the findings, contemplate the issues and suggest ways forward. 1. That a majority of women would sacrifice career progression for the sake of achieving “balance” in their lives. 2. That women are somewhat reluctant to undertake formal career planning, preferring to respond to opportunities if and when they present themselves. 3. That offers of career advancement within existing practices are often rejected by women as they question the capacity of the advancement to satisfy their career aspirations. 4. That there is a high level of satisfaction amongst women with their current jobs in terms of balancing work and personal lives and having control over their professional activities. 5. That there is a low level of satisfaction amongst women with their current jobs in terms of remuneration, present rate of career progress and long-term career opportunities. 6. That the most important career goals for women include building their own practices and taking on new project types and professional challenges. 7. That the greatest barriers to career progress experienced by women in the profession include family commitments, lack of time and poor relationships within the industry. 8. That by the time women retire, they hope to achieve professional satisfaction and the completion of benchmark projects that make a difference in cultural and environmental terms. 9. That women believe that career progression is based on previous performance and technical competency, compatibility with management and staff, as well as having an ability to bring in work. 10. Given that women believe “you are only as good as your last project”, the discontinuous pattern of many women’s careers is potentially problematic. 10. Given that women believe “you are only as good as your last project”, the discontinuous pattern of many women’s careers is potentially problematic. 12. That personal satisfaction and client satisfaction are the most meaningful measures of career progression for women.

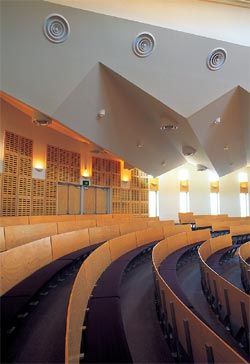

DIANE JONES, PRINCIPAL DIRECTOR, PTW, SYDNEY

Court 3, King Street Courts, PTW. Photograph Christopher Shain.

As an architect who has always been interested in projects in the public realm, the findings of Going Places make me more determined than ever to help find ways for women architects to take active and senior roles in large practices such as ours.

The survey speculates that little may have changed over the past twenty years; however, the presence of many women architects on the stage during the recent National Awards, and the activities of professional associations such as NAWIC and the Women in Development group of the UDIA, suggest otherwise. There are now alternatives to having to walk into a room full of men in order to “network” with others in the construction industry.

Despite this, the changes are slow and small. We all have anecdotes about the stereotypical attitudes that impact on our work or on our relationships in the profession: about references to “the girls” as a way to diminish the validity of 250 pages of defects; about unreasonable “toughness” (translate as thoroughness for a male counterpart); about being too emotional.

And we have all no doubt come away from meetings exhausted from the effort required to counteract the wave of testosterone expressed either as battling egos or bullying. One can develop strategies to deal with these situations.

And we all know of many architect couples where the woman was regarded as the more highly skilled or talented but has accepted taking a major family role and a minor architectural role, in contrast to the man. Similarly, the skills of many architects who work part-time are poorly utilized.

If you are a woman architect who wants to work in a medium to large scale practice on a wide range of projects, and also wants to have children – and don’t have a husband/partner whose temperament and vocation allow them to take the major share of home responsibilities or don’t have the resources or inclination to have a nanny/housekeeper – how can you achieve this? Working from home on primarily small-scale residential work should not be the only option.

I think that large practices need to talk openly about the problems. These include: the view that part-time work has almost second-class status in an office; the sense of isolation that those working part-time experience; and the careful timetabling that women need to consider in order to establish a role and profile before having children, thus enabling them to return in a part-time capacity to an office that knows and appreciates their worth. It is very hard to be away from the environment of a medium or large practice for a number of years, while looking after young children, and then return to new technology and fee structures that allow little time for adapting or retraining.

Unfortunately the profession, as it is currently structured, often demands long hours. And resentment builds up if one person in a team needs to leave early or can’t work the “all-nighter” to meet a competition deadline.

I think the way forward has at least two parts. The first is the responsibility of those of us in large practices to “speak up” clearly and loudly when we believe that gender prejudice is influencing the way that our team members are being treated, both within the practice and by others.

Secondly, we need to discuss openly with women architects who have or soon intend to have children, how to address the issues outlined above. The solutions will, I think, differ for each individual and may indeed vary depending on the projects that a particular team is working on.

The basis of such solutions needs to be understood by the other members of the team and of the practice. Just as gender should not preclude opportunities within a practice, nor should it bestow “favours”.

Indeed, such flexible modes of working should be available to all in the practice – men and women – and at all levels of the practice, subject to well founded management and economic imperatives.

These issues must be earnestly addressed, practice by practice, if we are to allow the energy and skills of highly talented women to contribute to our profession across the full spectrum of projects and roles.

DR SANDRA KAJI-O’GRADY, HEAD OF ARCHITECTURE, UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, SYDNEY

House for Deena, Elizabeth Watson Brown Architects.

I am currently Head of the Architecture School at the University of Technology, Sydney – one of four female heads of an architecture school in Australia, and one of only two that has come to this position through a professional architecture degree.

I have been working in academia since 1995, and often wonder whether or not I would have succeeded in practice.

I graduated in a recession in Perth and none of my classmates got work without going overseas. Several of us now teach, but some of those who did venture to Asia have been extremely successful. My first position as a graduate architect was with the state government. Of the hundred or so architects – in an office then known for encouraging experimentation – there were five or six female architects. Being a state government department, there were laws addressing equal opportunity for women in the workplace, but this didn’t prevent female architects being assigned to design childcare centres, primary schools and heritage projects, or, worse, to writing reports. When a junior male colleague was given the plum job of designing an extension to the art gallery and flown around Australia to view similar buildings, I decided I had had enough. These were buildings I knew well from my own self-funded trips to view art. During this period of practice, I also completed a Diploma in Women’s Studies at Murdoch University which helped a great deal. I was able to recognize that discrimination was a structural issue, not the consequences of some personal failing, while others around me saw themselves as responsible. Perhaps, this is one of the most useful outcomes of Going Places – it reminds us that many of the experiences and concerns women architects have are shared, and the product of larger cultural issues.

One of the attractions for me of academia is that the routes through promotion are much more transparent than in architectural practice. Additionally, universities are actively seeking to redress the lower representation of female academics at professorial level and in senior management, though there is still a long way to go. I feel very well supported and that my contribution in teaching and research is appreciated by students and my supervisors.

Nevertheless, some male colleagues continue to operate through exclusive networks in less regulated areas, such as in setting up conferences and events. It is not uncommon to still come upon symposia (as opposed to referreed conferences) where all the invited speakers are men, even where the topic is generic and many suitable women could have been asked. When I confront the organizers of such events with their gender blindness, the answer is always the same, “We asked one and she pulled out”! As a consequence, certain conversations in architecture still seem very much gendered in Australia.

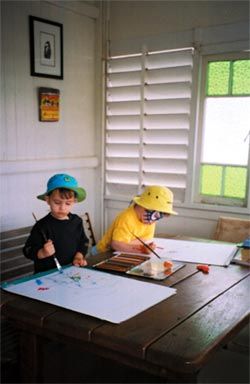

SHANEEN FANTIN, PART-TIME DESIGNER AND PROJECT MANAGER, STUDIO EDGE; MOTHER OF GABRIEL, 7 MONTHS, CAIRNS.

Shaneen Fantin’s nephews, Gus and Primo, painting on her front verandah.

How do we measure success? It depends whether you are measuring personal, emotional and spiritual success and fulfillment and whether that is tied to peer recognition. For me, peer recognition is important, but being happy in the morning and committing to socially valuable projects that may not get recognition within architecture is more important! And if my peers are my Indigenous clients then the two are very close. When is a client a peer?

I honestly think that some women do think differently about architecture to most men, and that some clients value that difference in thinking (and approach).

In my opinion, women on the whole tend to be more interested in relationships and interrelatedness, whether on a client, spatial, technical or management level. They are more interested in the journey than the product and are very good at making sure that the many complexities associated with creating architecture are considered.

Most of the time I hope that people will judge me as a human rather than by my gender. Nonetheless, on one occasion I did ask a man in my office to deliver an idea to an older male client because I knew the client would hesitate if it was suggested by a younger woman. In that situation I was passionate about the idea, not my gender, and any strategy would do.

I have come to my current part-time position through a varied career path – I have a PhD in Indigenous Housing, have practised in a range of types of architectural practices and have also worked as a full-time academic.

RACHEL NEESON, DIRECTOR NEESON MURCUTT ARCHITECTS, SYDNEY

Jesudason House, Neeson Murcutt Architects. Photograph Brett Boardman.

So few registered architects are women!

Although I know many “successful” women who are unregistered, in practice with or working for others, I do find these statistics alarming. But how does our profession compare with others? Is this really architecture specific? Or is it primarily to do with family? Is it, in fact, a broader social issue associated with our expectations about parenting – wanting to be with children, the structure of childcare in Australia (too expensive and too inflexible) and workplace legislation?

I don’t identify myself professionally by my gender – I don’t think of myself specifically as a “woman” architect – and I’m not exceptional in this respect. Most of my female colleagues don’t think much about it either, except for the difficulties of balancing parenting responsibilities and work. My non-architect friends who are mothers – planners, lawyers et cetera – have similar concerns. This suggests that the issues are broad cultural and political ones.

In my experience architecture is not a sexist profession.

Like the majority of the profession, what is important to me is the quality of the work, as benchmarked against the work of peers and as measured by them – both informally with colleagues and friends, and formally via awards, publication and talks.

This is how we can participate in a discussion about architecture and I find this discussion worthwhile, motivating, interesting. I agree with the majority of respondents that practice size is not a good indicator of success.

I am a director with my partner of a small four to five person practice. We don’t specifically employ men or women, although we are conscious of gender balance in the workplace. I have never worked in a really big practice and undertook a masters degree some ten years after graduating when I was already in part-time private practice.

So, what is the way forward? We naturally follow models. Perhaps we need more Kerstin Thompsons, Maryam Gushehs and Camilla Blocks – recognized architects and architecture academics who are also mothers and who seek to engage in professional discussion.

CATHERINE EVANS, NATIONAL CONTINUING EDUCATION MANAGER, RAIA

I am the National Continuing Education Manager for the RAIA. I studied architecture straight from school, tutored architectural students and worked in practice in Britain and Australia for about ten years. Eventually I found I was making HR and management decisions with no training. This, together with frustration at my limited opportunities to advance within the industry, lead me to undertake an MBA. The study encouraged me to look beyond working in practice, while the work I was involved with in practice at that time meant that I was liaising closely with a woman manager at the RAIA. She acted as a mentor and then provided an employment opportunity at an RAIA Chapter. Subsequently, she and my current (male) manager encouraged me to apply for the national role. Studying and moving outside traditional practice have enabled me to develop my professional skills in new ways, and to rectify my previous lack of career planning.

A number of the survey’s major findings relate to my experiences. Like many respondents I want to have a successful career, but “balance” is critical, as is success on my terms. The most relevant finding for me is that women may have different values and measures of success than those generally held by the industry.

The survey findings about satisfaction with balance and remuneration are completely contrary to my experiences in practice. I sought tangential opportunities outside practice because I was dissatisfied with my work/life balance, and my control over my professional activity. I was also dissatisfied with remuneration, progress and opportunities, but I am starting to find satisfaction now.

For me, the difficulties in advancing my career have been: thinking and expressing myself differently to men, having slightly different values, and not finding mentor support within traditional practice. I have never quite experienced these things as “barriers”, they just made things harder in an already difficult profession. To be heard I felt I had to translate my words and actions to be more masculine, and so was constantly working slightly against my character.

Ultimately this is draining and not that successful or satisfying.

This has been described to me as “sticky feet”, where each step is more difficult to take than the last. This is certainly how it felt to me – I started to run out of energy to keep struggling on. Differing perceptions of what success is are also part of “sticky feet”.

Having said this, I did receive much more support than my male counterparts when, early on in my career, I was working on site in Britain. I found contractors and consultants were much more helpful to me, as an Australian woman, than they were with British male architects, with whom they were much more confrontational.

Where do we go to from here? Well, we can’t all leave traditional practice like I did, but I have no suggestions.

EMMA WILLIAMSON, LECTURER, CURTIN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY; PARTNER, CODA STUDIO, PERTH

Williamson Wong House by CODA Studio.

I have attempted to read and respond to the Going Places survey on career progression several times over the past few weeks. As a working mother (two children under three) this has been a challenge. In my first attempt I ambitiously set the children up at the table with paints and paper, thinking I would read while they were occupied.

Hopeless. The intriguing cover and colourful graphs proved too much of a distraction. I placed the report back on the kitchen bench hoping to steal a few more minutes later on. Never happened, my youngest, Milo, became ill and I more or less held him for four days (no work). On Monday I put the report in my bag to take into work. Milo was still not looking flash but I was never going to get through the mounting pile of marking (and this response) if I didn’t get some time to myself so I dropped him at day care. I drove the half hour to uni. The phone rang when I got to the car park. Milo had a temperature so I turned around and drove back to pick him up.

Now, two days later, I have retrieved the report from the bottom of my bag. It’s starting to look a little worse for wear, but I am determined to read through it and reflect insightfully on my own career progression.

Maybe a coffee would perk me up and help me to focus?

Working in academia has given me a great deal of flexibility in my work arrangements over the past three years. I have had paid maternity leave and been able to nominate the number of days I wanted to return to work. These are luxuries that I know most women architects do not enjoy.

However, while the university is among the most family friendly employers, there has been a fundamental shift in my ability to advance my career while working three days a week. Pretty early on it became clear to me that the best I could hope for was to deal with the daily requirements of the job, a kind of crisis control. I definitely don’t get a chance to be strategic.

Maybe if I got more than four hours of unbroken sleep I would be more academically creative; I might even feel like knocking off that PhD if I didn’t feel like sleeping every time I read a piece of theory.

A more strategic approach would have had me complete or have substantially progressed a PhD prior to having children.

Now I would have to do this on top of looking after two small children. This is a significant additional commitment on top of my work and family responsibilities and realistically it would take eight years to do.

That is a lot of years of feeling bad about not spending time with my children or feeling bad about not spending time on my PhD. I am not prepared to take it on but cannot get a promotion without it. So my academic career is at a complete standstill.

The report does resonate for me, particularly as my attitude toward my career has shifted since having children.

Family commitments mean that I have significantly less time to devote to work.

Disjointed work patterns and reduced working days have resulted in less output.

My measures of personal success (and failure) are no longer primarily hinged on my career but have broadened to include the wellbeing of my family.

I know many inspiring, creative and driven women who seem to exist comfortably within the profession. But I found that there was a fundamental shift when I had children. This has impacted significantly on my career advancement in ways I was not totally prepared for. I can’t say that this was because of architecture, I think that it is a result of working less and feeling totally exhausted.

I am currently a lecturer at Curtin University of Technology, but am about to make the transition to working in the practice I share with my husband, Kieran Wong (CODA). I plan to work three days a week, although this will fluctuate depending on family commitments.

I have sought an array of experiences throughout my professional life and have constantly sought to be involved in a variety of design projects – building design, speculative work, exhibitions, product design – in addition to teaching.

SUE DUGDALE, SUSAN DUGDALE ARCHITECT, ALICE SPRINGS

Alice Springs Cinema, Fourth Auditorium, by Susan Dugdale Architect. Photograph Sue Dugdale and Nancy Lau.

I have run my own practice since 2000 and have two employees. I have arrived at this via a slightly varied career path. In my year out I worked as a builders labourer (a deliberate choice to fix my appalling lack of construction knowledge). After I graduated I was part of a fashion design business, I tutored at Melbourne Uni and RMIT, and did some building work. Then I worked in Melbourne practices until I went to work for an Aboriginal organization in Alice Springs.

This was out of necessity (I’d just been made redundant) but it opened up a world of interest and opportunity for work in Central Australia.

I agree with the Going Places findings about balance, satisfaction and career goals, but other findings do not reflect my particular experiences.

I always knew that I wanted to have my own practice. I had a plan, but I have also been open to opportunities and change when they presented themselves – this is how I ended up in Alice Springs.

My remuneration was a mixed bag in my earlier years, but has been good since starting my own practice. I assume that what I pay my employees reflects how much I value them, so I use salary as both encouragement and as an indicator of worth to the practice. I believe strongly that architecture practices are not quarantined from the value that society places on remuneration as a measure of the worth of the work done by employees.

I don’t have kids; if I did, I expect family commitments would affect my work more than they do. I’ve generally had good relationships within the industry. However, I do have to resist the urge that a lot of women feel to be “nice” all the time.

Sometimes this is not appropriate.

Living in a small town (Alice Springs’ population is 27,000) helps a lot with networking and establishing a reputation.

The downside of being in a small town is the lack of peers and peer activities such as talks and seeing work by other architects.

I get a lot of satisfaction from winning and carrying out larger projects, receiving awards, and getting journal coverage, though it took me a while to acknowledge this. I did not attend either of my graduation ceremonies as some kind of anti-establishment gesture, and used to put down journal coverage as shallow and ego-driven. However, when I won an RAIA NT Chapter Architecture Award, I was surprised, to say the least, at the measure of pride and enjoyment I got from the publicity and the approval of my peers (and friends and family). Now I feel that although awards aren’t a primary ambition, they are in a strong second place. Perhaps many women don’t value this approval and recognition because they don’t expect it, and therefore don’t seek it out.

The feedback I get from clients and builders suggests that many women manage relationships with clients and builders better than some men. I hear of autocratic and arrogant male architects on site, and of male architects who never really listened to clients’ requirements. This may be both a perceived and a real advantage.

Where do we go from here? One thing that can help is building the confidence and skills of young women architects through mentoring by more experienced architects (men and women, though especially women), and perhaps by having RAIA awards for smaller-scale work.

In the 1980s, I was part of an open group that met every Queen’s Birthday weekend for a retreat out of Melbourne that we called the “Women’s Winter School in Feminism and Architecture”. It ran for about ten years and was very much a product of its time. It was invaluable for peer support, ideas, networking, and in formulating one’s own values and sense of self as an architect. Is there a possibility for a contemporary version of this?

Overall, I think gender has been hugely influential on architectural careers, but that it is less so now.

JANE WILLIAMS, DIRECTOR, STATE MANAGER AND BOARD MEMBER, BLIGH VOLLER NIELD, MELBOURNE

I never think of myself as a “female” architect. I am an architect. I believe people achieve their best, regardless of gender, when they are empowered; when mistakes are tolerated and encouraged; when there is trust and clear role definition.

For me, the last finding in Going Places is the most relevant: I consider both personal satisfaction and client satisfaction to be meaningful measures of success.

Architecture is a difficult profession and it is immensely satisfying when clients appreciate what you have contributed to their lives and those of others’.

I am not surprised by the finding that family commitments are seen as the number one barrier. What I find interesting is how many respondents felt that a lack of professional support was a contributing barrier. This needs further investigation – men may also perceive it as a barrier, and it goes to a broader issue of continuing professional education. Professional development is a real issue for employers seeking to attract and retain the best people, as well as being a requirement for remaining registered. How well do we understand what people want in terms of professional support?

Having autonomy and choice over the direction of my career has been important to me. As an architectural student I made a very conscious decision that I wanted to experience a variety of practice types, as well as academia, and I have actively sought out such experiences. I was also very clear that I wanted to work on large-scale projects, which, for me, meant moving interstate. These were clear objectives founded on the desire to gain diverse experiences rather than career progression.

My career has progressed and morphed in various directions with the support of my peers. I am now a partner in a company I have been with for eight years, practising in both Sydney and Melbourne. This has given me diverse project experience as well as exposure to managing and now leading a practice. I have been proactive in making choices and have taken opportunities when they presented themselves.

In my final year of studying architecture over half the students were women. A number of these women are not practising architecture in the traditional sense now.

Some have diversified into related professional areas, including academia; some have changed profession completely; some are working part-time while pursuing other interests; some have stopped work to have families; some have worked in large commercial practices and now continue to run sole practices while having children.

I believe there has been a recent shift towards better supporting women in architecture through policies such as paid parental leave, part-time work and other incentives. In 2004, Bligh Voller Nield implemented a paid parental leave policy that is non-gender specific. It recognizes that men also have family responsibilities.

This is an important addition to other company policies, including equal opportunity and providing financial support to become a registered architect.

These recognize the need to support employees in various ways – not just those employees having children.

The likely challenge facing architects, men and women, is being able to work in effective environments that allow the individual to achieve their best while supporting other aspirations – families, home ownership et cetera. For many architectural graduates, regardless of gender, the biggest challenge is to be able to afford to buy their own home, and this is becoming increasingly difficult. The biggest challenge for employers is understanding the combination of Y and X Generation and Baby Boomers in the one workplace and their needs.

SUE PHILLIPS, CO-DIRECTOR, PHILLIPS/PILKINGTON, ADELAIDE

New chapel for Pedare Christian College, Phillips/Pilkington Architects. Photograph Grant Hancock.

I am co-director of a seven person practice in Adelaide, which my partner and I established in 1992 just before our son turned one and prior to the birth of our second child the following year. Before starting our practice, I worked for a large Adelaide firm for about five years and was the first woman architect to be given maternity leave there. This job followed almost four years working in London interspersed with travel. My first significant job after graduation was with Mitchell/Giurgola & Thorpe on Parliament House which was a wonderfully supportive initiation into the architectural profession.

While I didn’t participate in the survey, many of the experiences described by respondents resonated with my own, particularly the impact of family commitments on my career and the constant sense of a lack of time. The survey emphasized the impact of family on career, but I also have a guilt-ridden sense of the impact of my career on my family. Guilt, I think, is part of the territory of motherhood, and the constant battle in time management between work stresses and family pressures can occasionally lead to a sense of failing on every front. My children, I think, are growing up to be resilient and well organized to compensate for their sometimes distracted parents. This may be post-rationalization on my part (but as architects, we specialize in postrationalization).

Being in private practice has helped me juggle the work/family dilemma.

I’ve been able to be involved in school activities without having to ask anyone for time off. I’ve also had more flexibility in dealing with sick children, which is a nightmare for many women with inflexible employers.

Lack of flexibility in working hours is, in my view, a major impediment for women’s career paths, with many women opting out of large-scale practices during their child-raising years. Part-time work is often seen as incompatible with running jobs on site, being available for clients and meeting deadlines. I believe that practices need to promote alternative methods for running projects with the role of project architect being shared. Over-reliance on a single person to know everything about a job creates problems of job continuity for both males and females during holidays, sick leave and compassionate leave.

For me, one of the most interesting outcomes of the survey was the marked difference in the respondents’ perceptions of what constitutes success and what they believe the profession as a whole sees as indicators of success. Women, it would appear from the survey results, perceive themselves to be less reliant on external validation of their work than their male colleagues.

This accords with my view that in a still male dominated profession, the “Architect as Hero” is alive and well, reinforced by the personality cult of the “masters”, which architectural histories and popular culture perpetuate.

Venturing into the dangerous territory of sweeping generalizations, I believe that young male graduates tend to present more confidently and ask for help less frequently than their female contemporaries, perhaps bluffing their way through difficult situations. As a consequence, they wear the “Architect as Hero” mantle with greater ease, which contributes to a faster progression in large offices.

I would like to see more women in senior positions to mentor others and to assist in the development of family friendly work cultures, which will benefit both men and women. I believe my practice has benefited from having a woman director. For example, having a woman present in selection interviews has worked to our advantage.

With a relatively small pool of senior women in practice, I have been on a range of committees, panels and boards. This has given me greater insights into Adelaide’s architectural and political scene.

It has also helped to contextualize our practice and to avoid the isolation often found in small practices.

The survey is an admirable initiative and I support all the recommendations. I look forward to the results of the proposed “Men in Practice” survey and to comparing the varying perceptions.

ELIZABETH WATSON-BROWN, DIRECTOR, ELIZABETH WATSON BROWN ARCHITECTS, BRISBANE

Is “career progression” the right question?

It is so different from the way I think about what we do in my small practice. The notion of “progression” fits better with those “careers” that are best measured by the ladder rungs of promotions. This is not how architects, male or female, generally measure career success or satisfaction.

I suspect that the production of good architecture is the ultimate measure of success for all architects, male or female.

The quality of the building is independent of whether they are large or small, or whether they were created by large or small entities. However, it is true that it has been difficult for women to gain senior positions (and therefore autonomy, control, influence) in large corporate firms.

In my case, I knew early that if I wanted to make buildings “my way” I needed to create my own structure in which to do that. I knew that it would have been really difficult for me – especially at that time (late 1970s, 1980s) and with my personality (not so confident or pushy) – to create that opportunity for myself within the existing structures. It’s probably easier for women to have autonomy and control over opportunity, output and life by having one’s own practice in one’s own name, rather than in a large firm or in partnership with a bloke.

So, concepts of “career progression” in architecture may not be gendered. But what is gendered – and also generational – is how we navigate our way through our working lives and our personal lives. Gendered, generational, but not career specific.

I suspect the findings would be similar in any profession. Gender is a factor for my generation, but probably less so for the next. Our own kids are working things out much more practically than we did, as are my own younger employees. The slow grinding cogs of political and societal change will follow.

Not complaining! Men are also disenfranchised by the practical and political strictures of work expectations.

Working women have, of necessity, had to be creative thinkers and supremely flexible and intelligent to resolve the work/life equilibrium. This comes reasonably naturally to most women, and it is precisely the ability to think and organize like that which makes good architects.

In the blokey world of our particular coalface, the building site, ALL architects are de facto “girls” anyway! Maybe it’s better to actually be one. The qualities attributed to a good design architect are essentially the “feminine” stereotypes – understanding, ability to listen, ability to distil the essence of complex problems with many dimensions and layers beyond the merely spatial, ability to think on two sides of the brain simultaneously! The best architects, male and female, have these qualities.