Jury Citation

Greg Burgess in his office.

Light and shadow.

Frond breaking through asphalt.

Gregory Burgess is recognized as an architect of great distinction not just by followers of his work in Australia, but throughout the world. Though his work has been published widely, Burgess maintains a low profile. He does not seek publicity through theoretical debate but rather promotes his architecture through finished building works and writings that are closely followed by the architecture and fine arts community. Peter Davey, editor of The Architectural Review, has included Burgess among a select group of architects worldwide who “are trying to find ways in which human values can be expressed against the alienating and normative forces of the global economy” and who “tend the flame of hope and carry the lamp of truth in a world that seems increasingly to have no values other than profit and the market in its grossest form”.

Such an accolade is supported by Burgess’s completed buildings, which have been published internationally since 1985 and have received more than forty awards during the last twenty years. In 1997, Burgess was awarded the internationally prestigious Robert Mathew Award for outstanding contributions to the development of architecture in the British Commonwealth. His designs for houses, schools, community buildings for health and cultural interpretation, exhibitions, ecclesiastical and institutional buildings, and most importantly his work in designing innovative buildings with and for Indigenous Australians are all rich with messages about nature, materials, and the fundamentals of dwelling, human interaction and public space.

Greg Burgess’s design philosophy has application across all cultures and his record of sensitive and distinguished activity as an architect is explained by his design philosophy: “Towards a Community Architecture of Wholeness”. One part of this reads:

To understand the origins and purposes of life in its myriad forms and in its totality is an ancient aspiration of the human being. It sustains our journey towards wholeness. It urges us to reach deep into ourselves, high above ourselves and into all things, so that we can bear, celebrate and share the fruits of our journey.

The architect has a uniquely powerful medium in which to make this journey. When we enter the mystery of the creative process, the forms we make embody ourselves and bring into dynamic and living conversation what we were, what we are and what we could be. The manner in which these forms flow out from us affirms our place in the wider world of community and nature.

As a mentor, a teacher, a director of the Sophia Mundi Rudolph Steiner School in Abbotsford, Melbourne, an active participant in government and community forums about art and design, and above all as an architect of deep cultural sensitivity and consummate skill, Gregory Burgess is a fitting recipient of the 2004 RAIA Gold Medal.

RAIA Gold Medal Jury, 2004, David Parken, Graham Jahn, Brit Andresen, Christine Landorf and Philip Goad.

Room Temperature

“Enter, open, enter”, Architecture as Idea exhibition, 1986.

Johnson house, skylight to dining room ceiling, 1984.

When I was informed that Greg Burgess had been given the RAIA Gold Medal for 2004, I was surprised that this honour had been bestowed again beyond the boundaries of the Commonwealth of New South Wales and its satraps. No, seriously, I thought it was recognition long overdue and a credit to the RAIA, and I hope this year at the investiture, Canberra remembers to bring the medal. This news prompted me to remember the deserving case of John Mockridge in an earlier era, when moving upward was done by stepping on other people’s necks, and John was gay and witty.

At a funeral I recently attended in Springvale, the magpies warbled, the parrots screeched and the cicadas were interminably noisy. Bark fell from the ghost gums into the grave and the heat and smell were unsettling but familiar. Off to the side a small vigorous group discussed a recent stock exchange imbroglio. Throughout I was struck forcibly by evidence of how ill-fitting and brave was the European diaspora in this country. Of all the late-twentieth-century local practitioners, Greg Burgess has attempted to connect us with the old enduring forces, namely nature (the perplexing Australian version), community, belief, decency, rites, meaning and rituals. The complete package.

He has attempted to direct us to an inner sense beyond the world of signs. Greg has always dealt in main event architecture. The integrity of his work has continually won him admiring support and an extraordinary number of proper awards.

The work produced in the Burgess office shows the clearest sense of self as well as the particular dignity that comes from working in the marginal. A beautiful and personal office and a talented and loyal staff is particularly noteworthy. Artists have a healthy appetite for approval but in general they are dissatisfied with the world as they experience it. Any attempt to spiritually improve our lot is nowadays usually met with world-weary condescension at best or anger at worst, the latter from those in this country committed to the earthly paradise argument and all that that entails. The Burgess practice has been penalized for its ideas. It smacks of the intellect and this is not a widespread commodity in our profession. Is this the result of staring at water for long periods of time?

How do you mend a broken heart? You wait for the scar tissue to heal over.

Architects are usually less than radiantly warm on the bitter subject of jobs and opportunities (real or imagined) lost to fellow practitioners. Greg Burgess has not complained. For example, his office had tenaciously held close to the National Museum of Australia project in Canberra for over ten years and had seen prime ministers (and their favourites) and governments come and go. When the job was eventually won by Ashton Raggatt McDougall, Greg was straight onto the front foot and his letter of congratulations was the first in the door.

It is one thing to have that rare gift, an architecture vocation; it is quite another to pursue proper behaviour and generosity of spirit. Gregory Burgess, who could play football a bit and carries himself accordingly, has built both a financially stable and historically significant Melbourne practice based upon talent, belief and decency. It is a model for this country.

Peter Corrigan is a director of Edmond and Corrigan Pty Ltd and teaches at RMIT University. He was the 2003 RAIA Gold Medallist.

Golden Boy

There are a number of Greg Burgesses. The first was the strapping young student in our first year at the University of Melbourne during 1965. He was athletic and smart – with a suburban-army-haircut – quiet, and a nice cut of a lad from Box Hill who played football with Hawthorn. He attracted the attention of a similarly “A”-listed student, Sue Whiting, and they later married. In the late 1960s he travelled for a year to Europe, went north, came back emaciated, long-haired, enveloped in a deep fur coat – looking like a fit John Lennon. There had developed a smoky haze about him, and he went on to graduate among the top of his class.

Later, his career was developing with carefully crafted domestic buildings which were characteristically like Kevin Borland’s timber-and-bolts, but veered further to the edge – to Bruce Goff country. He was holding traditional suburban ground while searching much further out.We shared space (with Corrigan, Edmond and Crone) at the 1979 Melbourne Four exhibition and, again, Greg was agile enough to put it together and intelligent enough to place his architecture in a special category. I think that exhibition helped us all to self-realize.

There were, and are, two sides to Burgess. I like to call him “a dingo in a matinee jacket”. On the one hand, he is unassuming, caring, respectful, thoughtful, aesthetic – soft, even. His architecture is meek but forceful. Buildings he designs are “Burgess buildings” – individual, creative and respectful of his relationship with his clients. But on the other hand, he has a stainless steel mind, an austere humour and the resilience it takes to forge a strong, individual body of work over thirty years that is already part of history. To survive in this profession, and create great buildings in the process, is a special skill and Burgess has it. His temperament is inquisitive and his lasting pairing with Pip, who is herself a noted artist, has developed their single entity into one stronger than the two individuals, which allows him a freedom to create without fear. But he is also an ambitious commercial architect and a good storyteller. Most people who hear him speak fall in love with him, and many become his clients and then friends.

Still, he surprises me. He gets mugged in Brazil, finds a special place with the spirituality of religion, teases out a trusted role with our animist Indigenous cultures and, of course, achieves notable international and local acclaim. Yet he remains the sturdy kid from Box Hill who remembers his friends and can relax easily with them. Maybe my two Greg Burgesses are really – likeable, gentle person; and someone who happens to possess a luminous talent. Either way, those lucky enough to experience a Burgess building will understand why most of us know him as a golden boy.

Norman Day is a practising architect, adjunct professor of architecture at RMIT University and architecture writer for The Age.

Butterflies, Biodynamics and Burgess

Naturally I do not know all the Gregory Burgess buildings in the world, nor do I know all the trees or butterflies, but I know enough to be sure that I am thoroughly in favour of them all and I am convinced that the world would be a more enchanted and livable place if adequate supplies of these things were available in the ordinary daily manner.

“If only Burgess had designed that building” is a recurrent lament in my disillusioned traipsings through the hardening public domain or past the latest awardwinning architectural calamity. “What a pity, what a tragic disgrace,” I hear myself moan as I come upon yet another vain assembly of cruel steel and glass piled neurotically (and for the rest of my life) onto a prominent and significant site in the city of my birth.

With the proliferation of harsh architecture it is easy to imagine why harsh things are being said about architects. Arrogant. Egotistical. Tight-arsed. Emotionally retarded.

Up themselves, etc. It can even be imagined in certain states of delusion and despair that cruel architectural acts should be declared crimes against humanity with penalties just short of prison, public flogging and deportation. Perhaps chain gangs of architects should be forced to dismantle their buildings with sledgehammers or offenders could actually be forced to eat their buildings over an extended period of time, piece by tiny piece. How else can they be made accountable? The global market economy has failed to do it as promised and in fact appears to have made them worse. It’s fun and possibly therapeutic to hate architects and want them put on trial and punished for their part in the ruination of your city. But it’s all a pipedream, for they get awards and prizes instead, by the skipload, and are much fussed about in the press and can do quite well in the fashionability stakes as if they were genius winemakers and cult chefs. And lately there seems to be a lot of photographs in newspaper lifestyle sections of neat and coollooking whiz-kid architectural teams who are winning important overseas contracts. I congratulate them but these photographs bemuse me, not just because the protagonists often resemble groovy dental technicians but because, unlike the pictures of the foodies and winies, there are never any lovable or jovial organic elements to be seen in the pictures such as grapes and sausages and certainly nothing as glorious as butterflies (which I mentioned at the beginning). One wonders whether the profession has got, not just an image difficulty, but also an actual Eros problem. Contemplating the evidence – the constructions, the photographs and the anecdotal stuff (including the earthy testimonies of builders) – it appears that something vital, something natural and biodynamic, could be missing; and even worse, it could be strongly repressed. Perhaps it’s the incongruity which comes from putting human faces to all that sharp and thrusting, angular construction but it feels like there is a trauma in the profession which, in spite of all those personal reputations, makes it difficult to work as a humanist in the truly personal way.

Let me now bring some of those butterflies into this. Are they welcome here? How about some sausage? Let’s have some grapes! Now I’ll just drink three nice glasses of red wine and ask some questions about architecture. Lovely! OK, here we go!

How can you design places for humans to live, work and play in if you have not had epiphanies with butterflies? How can you draw a true, imaginative line unless you have found instruction in their elusive and vibrant flight paths? How do you make a beloved and delightful structure unless the sudden, mysterious appearance and disappearance of butterflies has, at some crucial moment, redeemed your wretched, floundering heart? And how will you put grace and guts into a public building unless you hold sacred the cocoons and revere the astonishing, confident relationships of butterflies with wind and foliage? How can you offer something truly valuable to life unless you first proclaim to yourself the miracle of the butterflies? Yes, another glass of wine, why not!

But not just butterflies of course; trees too and mountains and history and love and human suffering; grapes and sausages as well if you like; these are but a few of the myriad vital and enduring organic templates for human creativity; spiritual realms with natural movements, shapes and structures which can be held and integrated as supple poetic truth which brings me precisely back to Burgess … for it is upon this truth, I declare with empty glass in hand, that Gregory Burgess sharpens his pencil to do his work.

Now, as much as I give thanks for and take heart from his work, it strangely also bothers me because there is far too little of it for my liking: not because he is unprolific or unwanted, quite the contrary; it’s just that, unfortunately, there is only one of him and the world is so huge and needy and, like the rest of us, his days are numbered. Funnily he reminds me not so much of architecture but of what architecture needs to recover. I insist that this is not a negative vision but a poignant hope.

Though the world be short of Burgess buildings from my impatient and worried perspective, he is very much a strong, ongoing and authentic force and has created and contributed much. But he has assimilated and distilled much, too, not in the consuming way but in the sacred sense, and therein lies the rare quality. Distillations from nature and human nature, from spiritual and organic process, from the rigours and wrangles of survival, from what is intensely personal and physical, from the land and Indigenous truth, from children and emotional life. How do I know? It’s obvious. It is there in his work. His gift is this unique spiritual alchemy and essence which he brings to bear so eloquently and reliably upon the concrete, practical world as a healing gift.

What use is an architecture that renders a society unhappy? It’s such bad design.

What’s the point in making a building that doesn’t heal or help or hold the spirit? It’s as futile as designing a room with no doorways. Architecture, like food, like wine, is a life support system and needs to be as organic as possible.

I hope Burgess leaves enough buildings to go around because there’s a huge need for them in the world we now have on our hands – enough at least for a new generation of Australian architects to use them as talismans of that essential supple poetic truth which holds great buildings and healthy societies together. If not, the butterflies and trees will have to suffice.

Michael Leunig is a cartoonist, writer and poet.

The Architect and the Gold Medal

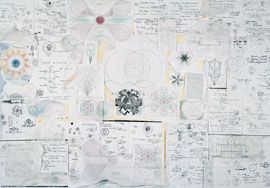

Process sketches for the Meditation Chapel competition (Japan) and A Place of Contemplationexhibition, 1987.

Vesica Piscesas process diagram.

Catholic Theological College: main stair, 1999.

Detail of sectional perspective from Meditation Chapel/ A Place of Contemplation.

A reflection on worth

I met the archtiect twenty years ago. He was working alone, in a narrow long room, in Richmond, the walls lined top to toe with raw pasteboard and timber models of buildings in various stages of assembly – shards, fragments, frames, skins, points and radii, spirals and cellular segments, the contours of excavated landscapes, of land scraped and cut, folded and returned somehow changed, somehow transformed. I thought myself in a museum of natural history, surrounded by collections of specimens: fantastic insects, fish and birds; skeletons of extinct species; wingspans of moths, butterflies and terns; the carapace of crabs and cicadas; the skins of snakes and manta rays. He said, “They are open to the quirky” – which might mean that they were a curious angle on things, that they showed a strange and oblique twist on the world. They were odd, queer. Something had gone awry. They were in torsion, transverse, athwart, even perverse. They were “the quiddities and queerks of logical dark”.

I saw him again last year. The collections of specimens, expanded and rationalized over the years, still lined the walls. It was a new office this time – dozens of framed awards, and a flurry of young architects.

But this time I thought the quirkiness in a different way. This time, as I wandered around, I was struck by this: that these buildings have personality. They make faces, put on airs, look askance, dress up in costumes, mess up hair, play, pose, mask, paint up, give cheek, brood, lean back, conceal, withdraw, show off. They are laconic, iconoclastic, idiosyncratic.

And yet the works are serious, and engaged in serious play. They are less about buildings than beings – beings in the process of building, in the process of coming to be. Architecture appeared to be about the advent of beings, building the quirky beings that they are, caring for the manner in which they are formed and carried, in particular ways, to become.

I also thought them careless and reckless, or at least risky. That is, the care taken is not in seamless resolution, detailing and assemblage.

Connections and joints are rough, slapdash, jarring, unsettled and in turn unsettling. The motif is one of discomfiture. Deprived of comfortable aesthetic resolution, the work is not-yet-finished,

not-yet-preserved, not-yet-ready.

An apparent carelessness, which is not without care, keeps irresolution moving within the fabric of the architecture – between site and buildings; between forms and masses; between spaces, rooms and corridors; between components, colours and materials. The parts tend towards each other without meeting. If they touch, they do so in passing – unsuspecting, almost by accident. The parts meet in difference and indifferent to each other, and yet they defer one to the other in coming to meet, in not-quite-yet meeting.

In other words, the work is incomplete – intentionally and necessarily. It shows the difficult and untidy process of transformation and completion in its very undergoing. If for Aristotle the function of art is to “complete” Nature, here it is to maintain configurations of incompleteness. The work is not-yet there, it has not quite-yet arrived.

Yet the process is not teleological or eschatological – it isn’t a question of ends, but rather of means without ends.

As a total opus, these works seem to be parts of an interminable process of transformation: a personality manifesting itself in its indefinite potentialities or prolongations, a science of embryonic deployment, a process of typological development. Each building seems to represent one stage of a total process of production, arrested at a different stage – so that each building contains all the others in potentia. In this lies both the fascination and the horror of the work, its delight and unease – if not disease, since, as interminable mutation, it can never rest easy, it must always be out of sorts, it must always be the restless “instability of becoming” – “at once anxiety and exultation, the risk and the transport of relation.” The metaphor of formal transformation in the work – geometries developing into others, spatial sequences leading from containment to release, gathering of horizontal space into the vertical, and so on – is itself a metaphor of personal transformation. The building becoming itself mirrors or parallels the individual being becoming itself. Hence the metaphors of evolution, gestural transformation and auto-production, leading to improvement: “Improve[me]nt makes straight roads, but the crooked roads without Improvement, are roads of Genius.” Blake may well have intended to compare Nature and Artifice. But here, if the work is crook, its crookedness is not a palliative to the artifice of the right angle. Rather, it is a question of suffering and undergoing. Its restlessness shows two things. First, it presents the designer seeking the work. Second, it presents the work itself, seeking itself, seeking a place for itself. In both cases there is a kind of desire and longing, an interminable questioning and enquiry – looking for form, asking for delineation, trying various trajectories and gestures of movement, exploring different configurations and assemblies. The work shows, tracks, records and crystallizes the traces of this enquiring and actualizing process.

This time, what I saw in these buildings, in spite of all appearances, was not form, edge, articulation, shape, light and shade.

The sense of appearance is not related to what things look like, but to their look: to the way they look (at). This is not meant to be spooky.

What I saw was an invitation to look between, beyond – somewhat like a personality or a potential that will not reveal itself all at once, but bit by bit, and always maintaining the right not to reveal. It is a matter of atmosphere, not form – a non-figurative, non-objective and nonobjectifying immersional experience, like being suspended within a mist, or surrounded by a queer and eerie air.

The work is serious, but I came to know that it doesn’t take itself seriously. It always holds something back – or rather, it always preserves a subtext, something unspoken or implicit. In that sense, the work teases, tests, provokes, leads on. To do this – neither to be too grave nor to trivialize – it has to let the reading waver, it must remain ambiguous. Consequently on the one hand it has serious intentions, and, on the other, it holds back from carrying them through. There is a sense of productive discrepancy, which allows the work to wander between the serious and the light-hearted. In this way, the work conveys a sense of interminable homecoming, a sense that things are in process, that thoughts are in train, that ideas are elaborating, that everything is always-already both arriving and not-yet-there.

I have written about the work many times; it has given me a place from which, or towards which, to write. I have often shown the work to students, and they always ask: “Do you really like this work?”But I have never come to the work aesthetically. It has always been more about gesture, about geometries of gesture, about trajectories of making, about an ethics of place. If the work makes possible a thinking, that thinking is not about the work itself, but maybe about work as such – how one works and produces work, and how what one produces works in different ways in different circumstances. It prompts a line of thought and initiates a critical landscape, suggesting something tangential.

Gregory Burgess’s work shows the value of modest shifts: that we might be grateful for the small scale and the incremental, for a whisper of something faint but weighty, an overheard phrase, something said in passing, an impersonation, a good yarn. These small gifts, fragments and measures of quiet insight and discernment, build a resonance all the more difficult to sense by dint of emulation and cliché.

I have come to the work again and again in different ways. It has given me words and phrases. It has given me to think, to diverge, to concoct, and above all to produce. This, at least, and aside from its now institutionally acknowledged value, is its worth to me – that it has helped frame a curious, risky and uncanny practice, in which there was freedom both to lose one’s way and to find oneself at home in homelessness.

Michael Tawa is a senior lecturer in architecture and coordinator of the Design Stream in the architecture program, Faculty of the Built Environment, University of New South Wales.

Invitation to the dance

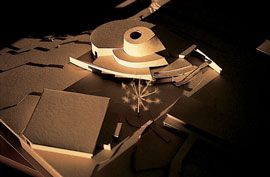

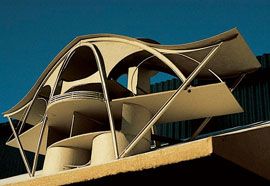

Victorian Space Science Education Centre model, 2004.

Michael Centre, Warrenwood, 1991.

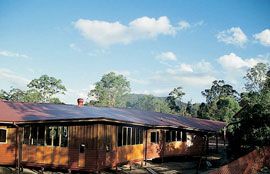

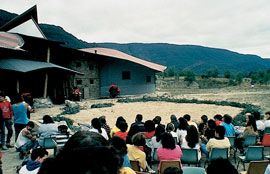

Samford Valley Steiner School, Queensland, 1995.

World of the Platypus, Healesville Sanctuary, 1994.

“Cathedral”, Sight Regained exhibition, 1993.

Sidney Myer Music Bowl Refurbishment, 2001.

Melbourne Four exhibition at Powell Street gallery, 1979.

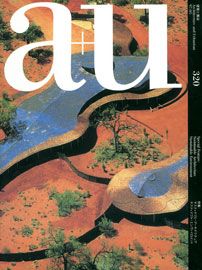

Uluru – Kata Tjuta Cultural Centre on A+U cover (Japan), 1997.

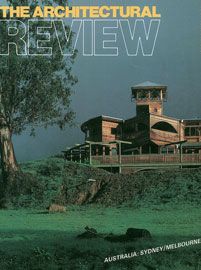

Hackford house on The Architectural Review cover, 1985.

Uluru – Kata Tjuta Cultural Centre on Architecture Australia cover, 1996.

Poster for Melbourne Four exhibition.

George Street apartments, Fitzroy, 2002.

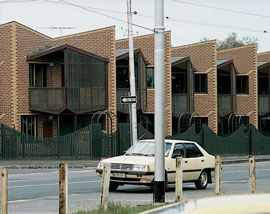

Ministry of Housing, Fitzroy, 1985.

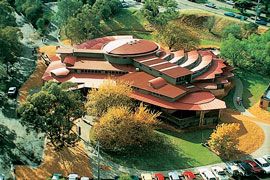

Box Hill Community Arts Centre, 1990.

Northcote Community Health Centre, 1986.

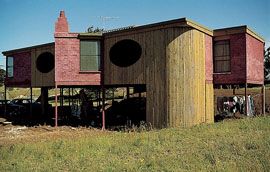

Fritsch house, Shoreham, 1976.

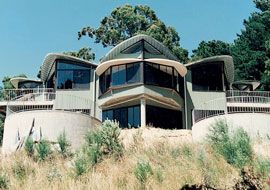

Windhover, Mornington Peninsula, 1983.

Larmer house, Donvale, 1977.

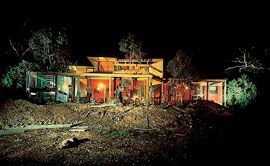

“The Earth House”, Mornington Peninsula, 1993.

Johnson house model, 1984.

Stutterd house, Eltham, 1977.

O’Dwyer house, Portsea, 1987.

Brambuk Living Cultural Centre, Gariwerd, 1990.

Eltham Library, 1994.

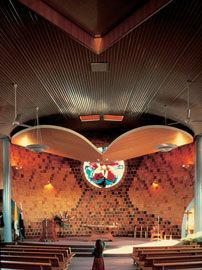

St Michael and St John Church, Horsham, 1987.

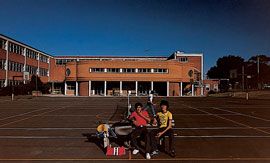

Catholic Theological College, 1999.

Prahran High School Library, 1978.

tockman’s Hall of Fame competition model, 1980.

Exhibition design for The Completion of Engehurst exhibition, Sydney, 1980.

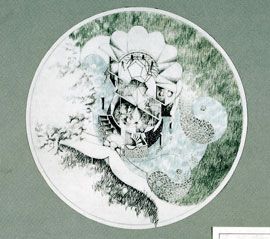

The Meditation Chapel competition (Japan) and A Place of Contemplation exhibition model, 1987.

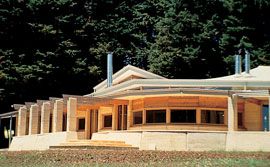

Twelve Apostles visitor amenity building, 2001.

Anderson house model, Marengo, Vic, 1998.

National Museum of Australia competition model, 1997.

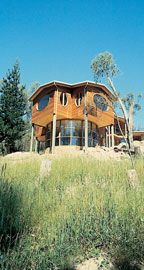

Burraworrin, Flinders, 1999.

Exhibition design for the Masterpieces from the Idemitsu Collection exhibition from Tokyo, Australian tour, 1983.

Exhibition design for the Treasures from the Forbidden City exhibition, Australian Tour, 1981.

They line the Richmond office in their hundreds: on tables, up the walls, cardboard and wooden models of two hundred or more Greg Burgess projects, brown and leathery like footballs, similar in scale, often set among model trees in aniseed plucked from the nearby railway lines. When Greg Burgess gets one down from the wall he handles it in both hands like a football, recalling his league games with Hawthorn in 1965–66. The projects go back to 1971: the Weston house at Anglesea, Barlow of 1972 at McRae with its sheared axes, then the Becker and Stutterd houses at Eltham, 1974–77, and the May house at Lake Boga, 1978. These early projects show a major concern with environmental function, through low energy and resourch usage, and an accord with their natural surroundings. (This has been sustained in Burgess designs through to the present, developing steadily in sophistication and technique.) Pole frames were the core of much of Burgess’s seventies work, and they remained, as episodes and referents, in house after house, on into the early eighties. The finish on these early houses is brisk and usually rough and immediate, like Kevin Borland’s houses at this time, and even here you sense the realization of architecture as becoming, of architecture representing the emergence and growth of an idea or belief – architecture that embodies the nature of an institution in built form.

Louis Kahn had set out how this would work, in his primarily static forms, for him archaic in their moment of realizing a building’s belief.Peter Corrigan, who had worked with Kahn, would soon energize this expression in his suburban-formed designs, each highly episodic, in the most exploratory of Australian traditions, and with the impacts, the collisions, the unfolding sense of the Bildungsroman, of the revealed life and growth of spirit, that marked northern Europe’s tradition of the expressive. The desire to include this spirit came from both Corrigan’s complex vision of society and his passionate engagement with the compressions of theatre. Greg Burgess moved this way, too, in his training in Denmark, his affinity for Erskine, Haering, Scharoun and Aalto. Like the Griffins, his early interest in Eastern spiritualities led to an engagement first with theosophy, then with the anthroposophical beliefs of Rudolf Steiner. Burgess was a founding parent and director of the Sophia Mundi school in inner Melbourne and has been involved in the design of Steiner schools around Australia – the Melbourne, Samford Valley, Kangai, Cape Byron and Orana schools of 1992–95 and the Michael Centre in Warrenwood of 1988–2003. He continues to work on educational projects, the most recent being the vortex-form Victorian Space Science Education Centre at Strathmore High School. In the process he has joined the world’s leading responsive architects – those who are often called organic. But his own work is broad in its cast and is eminent in a range of areas besides. He has gained equal success in his two Catholic commissions, the Horsham Church and the Theological College, and also in his Dutch

Reformed Church in Warranwood, of 1995. He has worked on a series of community arts and health centres and, unusually, has tested his ideas for more than two decades in a series of exhibition and installation designs.

Burgess has also designed a whole series of tourist and cultural centres. Brambuk and Uluru are the best known. In the experience of these landscapes and in the process of these designs’ emergence his connection with Aboriginal spirituality and ways of seeing was developed and heightened. This was cemented by sessions of living in Aboriginal communities. His dozens of houses, throughout the Melbourne suburbs and country Victoria, translate the experience of family and community into collective forms. In his landscape work, mostly in collaboration with Taylor and Cullity after 1988 (Taylor Cullity Lethlean after 1995), comes a set of insights into the character of forest, of contour and the texture of the ground. His World of the Platypus at Healesville Sanctuary, 1992–94, invites a whole exploration through its winding corridor and flanking arches, and seems to grow from the pebbled creek and pond around it. More recently he has gained a foothold in central city work, as in the Yuncken Freeman’s 1998–2001 Myer Music Bowl refurbishment, the two Koorie Heritage Centres and the Catholic Theological College.

Gregory Burgess has engaged several major streams in Australian architectural culture, and his work is crucial in both that diversity and in the synthesis that has come from it. By 1985 his Hackford house reached the cover of London’s The Architectural Review, as a summation of Australian tendencies, and a series of his projects have been covered there, in A+U and other journals, and have been included in a range of surveys, encyclopedias and exhibitions here and overseas. The workers and colleagues at his office are a gifted and extraordinary community whom Burgess has greatly appreciated, numbering hundreds and including many who have worked closely in teams and for long periods. There have also been a series of collaborations with artists, as when Stephen Hennessy worked with Burgess as a glass artist for some years, most notably at Horsham, and when Pip Stokes worked with him on the Griffin Review exhibition design of 1988 and the more recent Memento Mori of 2001. Burgess has also worked with Domenico di Clario on the Sight Regain edinstallation “Cathedral” of 1993, and with Paul Carter, in both the Little Places images and text, and in two 1997 competition designs – for the Melbourne Malthouse complex and the National Museum. Many other artists have collaborated too, particularly in the cultural and community centres, including Maggie Fooke at Box Hill Community Arts Centre.

The work itself is generally seen as having a major turning point in the late 1970s. At this time Burgess formed a life partnership with the artist Pip Stokes, and had his Powell Street exhibition with the architects Peter Crone, Norman Day, Maggie Edmond and Peter Corrigan. As he says, this prompted in him a need to define his own design and direction. This was reflected in his Stockman’s Heritage and Outback Hall of Fame competition entry, the completion of John Verge’s Engehurst in Sydney for the Pleasures of Architecture conference, and the project for the Place of Contemplation exhibition and Meditation Chapel competition entry – all from between 1980 and 1983. These projects were all marked both by a new diversity in his use of architectural texture and materials, and a new highlighting of “little things”. All reflected a greater self-searching in their architectural generation. This paralleled the rethink among Melbourne’s younger architects, seen in Halftime’s meetings and in Transition magazine, and Burgess figured in both. For him the emphasis was on design as the arena of a shared journey in spirit and in personal realization, as the Griffins had earlier envisaged. All his projects have since incorporated a strong element of spatial and thematic narrative, cast in quadrilles and spinning movement that invites one, as Burgess himself says, to enter architectural experience as in a dance, through and within divergent spaces and changing materials, textures and colour. Within this dance, the botanical, the geological, the line of force, the contradiction of spatial experience all mark Burgess architecture as they had the Griffins’. The real difference is in his willingness to draw in new ranges of societal and personal experience, and in a greater engagement with movement as both an ordering and an unfolding of narrative. This movement responds in a new and highly detailed way to Australian circumstance and context. This is why his designs from 1977 to 1979 onward read with a strong sense of earlier architectural forms characteristic of Victoria – particularly in their expression of extensions and bays, their sense of the folly or gazebo. Burgess designs proclaim their unity through agreement rather than through homogeneity. They show an acute sense of episode in composition and in texture. You see the grain and intervals of innumerable moments, visually, from the colonial period through to the early twentieth century, as in the elevations of the Hackford or O’Dwyer houses, of 1980–82 and 1986 respectively.

In fact the work breathes region and history. Thus the Hackford house, 1980, speaks of the gladed overlaps and gossamer agreements of Desbrowe Annear’s 1900s Eaglemont house – though Burgess does not claim close knowledge of them. Other Burgess designs such as the Sikkema project in Tasmania, 1981, and Windhover at Arthur’s Seat, of 1982–83, were moving in this direction, drawing on a whole range of suburban sources yet informed by ideal shapes, often in flora and with plans that swerve from symmetry. The earlier Grollo alterations in Thornbury, and the expansion of the Rockman homestead in South Gippsland, both under way in 1973–75, were arguably prototypes, as were the Fritsch and Larmer houses of 1976–77 in Shoreham and Donvale respectively. Of these Larmer is the early exemplar, pressing against its suburban boundaries with a tautness and force that recalls the territory of Federation and its particular kinaesthetics of site. The varied richness of the Larmer house’s texturing, the way it expresses movement, switching in episodic and seemingly arbitrary moments, allows Burgess to image the family refuge and identity in a characteristic commuter suburb. A logical continuation was Burgess’s Ministry of Housing work in Carlton and Fitzroy, 1981–83 – infill buildings that literally buckled against their small site boundaries and again had affinities with Federation movement and compression in their form.

The superb mesh of the Northcote Community Health Centre, 1983–86, is similarly guided. The site is across from the main shopping centre and its car parks. His design sustains the narrow compressed forms in Separation Street with their converging overlaps of small houses, paling fences and power poles

pressed up to the pavement.

In turn this reflected Burgess’s responsiveness to all manner of everyday architecture – often to what Australia’s architectural culture has seen as the proverbial ordinary and ugly. The staid public works architecture of Prahran High School was animated and given a new resonance by the ballooning, striated form of Burgess’s library and canteen. This was his first mature institutional design, built in 1978–79. (Now demolished in Victoria’s extraordinary school elimination program.) A chain of projects sustained Burgess’s responsiveness to the everyday, particularizing it and making it special, as the early Edmond and Corrigan designs were doing at roughly the same time. Burgess was among the earliest Australian architects – perhaps the first, with Edmond and Corrigan – to draw on the everyday suburban architecture that had flowed into many country centres as well, rather than lamenting it as a replacement of an often idealized rural vernacular. This is seen in a range of projects such as his reshaping of Stawell Community Health Centre in 1985–86, and in his linkage and transformation of the Rupanyup Hospital and Elderly People’s Home in 1987–88. A Melbourne suburbs design that preceded these – the remarkable Johnson house in Balwyn, 1983 to 1984 – possesses a form that dances. This house drew in the diversity of nearby institutional buildings such as the Grey Sisters’ hospice of the 1930s. It has courtyards, a monumental two-storey episode, and the walling turns into a front fence. The driveway takes on yet another character – as a walled service lane.

Box Hill Community Arts Centre of 1988–90 developed from an alteration scheme that turned into a new building. When it was being built it seemed to grow from the bungalow patterning of Station Street. Its bounding roofline and staccato patterning against the main street give it the same scale and kinetics as the Federation and Bungalow forms characteristic of Box Hill. The two great examples of Burgess’s Wimmera-Gariwerd designs – the Catholic Church of Saints Michael and John at Horsham of 1984–85 and the Brambuk Living Cultural Centre of 1986–90 at Halls Gap – are to a great extent at their most eloquent in their suggestion of urban forms and the particular responses carved into these. The Horsham church, one street back from the shops and highways, is again episodic in its changefulness and varied configuration from one moment to the next and is most striking in the way it picks up on varied regional city surroundings. The Brambuk design of Halls Gap recalls the vertical planked warehouses, cool stores and goods sheds of country towns, and takes on the fabric and textures of a township in itself. When it is read up close and episode by episode, one is haunted by this imagery – especially in the late afternoon. It resonates with the ghostly faces that gaze out from the photographs of the former mission people set out inside.

These designs, for all their responsiveness to context and circumstance, maintain the sense of being extraordinary, individual realms in themselves. Brambuk is ultimately a celebration of the great central tree form in an Aboriginal gathering place. Horsham and Box Hill gleam as jewels, glazed in tiling and crafted glass by a range of local artists and materials makers. In that sense both buildings sustain the meaning and detail of the arts and crafts in both the collaborative and expressive morality of their surfaces, inside and out. They have both a sense of care and specifics in the effort of their construction and materials that marks them both as repositories of bestowed affection. They evoke that desire for a detailed finish and permanence that, in its closest parallel, runs through the best of Australian postwar vernacular in a (now distant) light-on-the-hill optimism. For these reasons much of Burgess’s own discussion of these buildings has hinged on how they brought together all manner of the arts and crafts, and how they were to embody the heterogeneity of communities.

All this puts Burgess outside the Australian ideal of the freestanding dwelling – abstract, contained and exquisite. The geographical resonance and the communion with the natural and totemic world of the Uluru Centre of 1990–95 is matched by the densities and echoed age of the Eltham Library and Art Gallery, 1988–93. The library stands like a walled city on a hill, its internal columns and vaults a forest of Byzantine scale and possessing the intricacy of John Hawes’ spiritual utopia in the Australian West.

It follows that the Catholic Theological College, East Melbourne, of 1997–98, is compressed and emblematic on its Victoria Street elevation, spinning out behind to encircle the old Parade College. In the process it celebrates the richness of Melbourne’s Catholic learning and the diversity of training life in the succession of garden and sculpted events that run past its facets and curves.

In many designs Burgess draws near a notable Australian tradition – of George Sydney Jones and his polemics of episode in the 1900s, or Seabrook and Fildes in the unfolding fugue of line and event in MacRobertson Girls’ High School, where “Dudok” became something particular to its Melbourne site. In Burgess’s work this comes through in a range of projects, from the Ministry of Housing units and the Fitzroy apartments of 1981–2003 to the Koorie Heritage Centre in Melbourne of 1995–2002. The first version of this was almost complete when gutted by arson and it was redesigned round an existing building in King Street during 2003. In the first version, a single facade, deepened and layered by a sinewy

stratum of rods and twining across its front, gave the centre a dancing physicality to Lonsdale Street. In the great free style tradition of frontality and rotation, the drama of the facade was drawn into the entry foyer and then a paved passage curved through into a living history centre. This pattern is partly realized in the King Street rebuilding and it is intended that the layered facade will be developed in a second stage as funds become available.

Burgess’s ability to generate realms comes in part from his continuing involvement in exhibition designs. There is a long line of these and Burgess regards them as crucial to his work. The Powell Street Gallery show of 1979 set out the intricate range of Burgess’s own early work at its crucial moment of change. The Completion of Engehurst, another exhibition design, gave Burgess the opportunity to explore the generative processes of architecture along with an exploration of context. This translated into designs marked by outwardly expanding, flowering geometry. Engehurst was contemporary with Burgess’s Stockman’s Hall of Fame design, a vortex form of whirling circles and interlocking, superimposed shapes that established the form as both an institution – a dwelling – and a town form in its own right. Through the wider circles of its perimeter walling the Stockman’s design linked itself to the immensity of the landscape beyond. This design was seminal in the generation of Burgess’s later form and its sense of inscribing the landscape. This patterning, in all its restraint, power and detailed contemplation, runs through the Uluru centre, his National Museum design to the recent Cranbourne Botanical Garden pavillions of 1991 onwards. Burgess’s sense of the “realm” threads its way through a series of designs for visiting exhibitions: Aboriginal Australia in 1980, Treasures of the Forbidden City in 1981, Yangzu Province Art and Craft Fair, 1982, Idemitsu, 1983, and The Great Exhibition of Victoria, 1985 – a triumphal, tumultuous celebration of the Museum of Victoria as a teeming nineteenth-century compendium.

What links all these exploratory and exhibition designs is a search for balance between the diversity of circumstance and underlying patterns of unity. Burgess’s own notes on architecture return constantly to this theme as the dance, of reconciling spirit and soul in acknowledging opposites, dualities. These patterns are constantly resolved in a mesh of overlapping geometric forms, in particular the symbolic overlay of two circles, in turn allowing the expression of two proportionally smaller circles and a semi-elliptical patterning at the centre, the vesica pisces or fish bladder. This recurs in almost all Burgess designs after 1979, as a proportional system, a means of ordering space and a matrix for areas that are then often rearranged or reconfigured or spread out. Sometimes its form is expressed directly, as in the Victoria Parade entry to the Catholic Theological College or the unified structure and elevation of the Anderson house, a favourite but unbuilt project dating from around 1989.

Since 1980 the vesica pisces has been accompanied in Burgess designs by polygonal forms in juxtaposition and hierarchy, particularly the ten-, seven-, six- and five-sided. Each has its own reading for Burgess, a way of embodying – drawing together, opening, closure, expansion or compression. The Kabbalah tree is a recurrent image, and is seen particularly in his Museum of Australia competition design in 1997, which opened up as a township of linked areas on the Acton peninsula. The pathways were to read as branches and the destinations as leaves and flowers. Again, the linkage is radical: natural images forming a town or city. The link of the two resolves complexity and circumstance, making a dynamic of social imagery and natural forms, which controls and patterns the immensity of the project’s scale.

In the nineteenth century this fusion made Ralph Emerson’s Strong Poet and opened up Walt Whitman’s Democratic Vistas.

Engaging the spiritual in revelation, and the kinetic force of narrative as a sweeping line – as in the Flinders-Shoreham houses of 1996 on (Burraworrin, Alara, Johns and Boyd), the earlier “Earth House” of 1992–93, the Moorooduc Estate Winery or the Twelve Apostles Visitor Centre, 1995–99 – one is, in C.S. Lewis’s words, surprised by joy.

This experience is often found in work with quite limited physical or financial resources: such as the Minyip Health Centre of 1988–89, the Ironbark Centre at Bendigo, of 1997–99, or the Pheonix Park Community Centre in Chadstone, 1998–99. Burgess stretches the gesture in what can be done in a given set of physical resources, and so joins that Australian tradition of physically overreaching the limits of a budget or dimensional givens.

In the process Greg Burgess has gained a status rarely reached in Australian architecture. He has engaged a realm of the spirit while facing the daily struggle of construction, finance and regulations. In actual fact there has always been a struggle from one project to another as much in the Burgess office as anywhere else. There is the pressure to reshape and recast projects to fit a budget, or a change of brief. Yet Burgess holds to his vision, which is never static and which will not forsake its journey to find what lies beyond the next bend of the road. From this office comes work without complacency, work that fills one with anticipation about what is to come. Burgess has pursued architecture as vocation with a constant determination over the last three decades. His designs have gained the status of unique work and something equally remarkable – the undying affection of so many clients and communities.

Conrad Hamann is associate professor of Architectural History in the School of Literary, Visual and Performance Studies, Monash University. He is currently working on a monographic study of Greg Burgess.