|

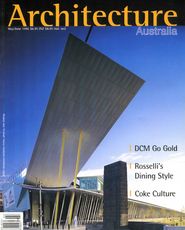

DCM’s 101 Collins Street seen from the Melbourne Exhibition Centre.

Australian Embassy, Tokyo.

Museum of Victoria, Melbourne.

|

John Berger described Picasso as a “vertical invader”, a vivid metaphor connoting an impatient upward thrust onto an elevated stratum, largely through his prodigious talent. There is something of the same force in the DCM partners’ rise to international prominence. They seem, well, far too young to have achieved their extraordinary success. How have they done it?

Synergy is now a cliché in the property business but it aptly describes the great strength of DCM. The whole is greater than the sum of the parts. The collaboration produces better, more profound, more rigorous work than any of the individuals could produce alone. They work in the same space on many projects simultaneously, at many stages of execution. The propositions are subjected to a rigorous testing like that of a team of research scientists who, having formulated an hypothesis, then set about disproving it. If the architectural proposition survives the test, it is confidently championed by the partner whose job it is to convince the client. The best of the DCM work has that inevitable logic which is a property of all good architecture. Unlike many architectural practices where each partner has a defined territory, the DCM responsibilities are blurred. All are designers, all participate in management and financial activities. Marshall chooses not to manage projects and spends more time than the others at the drawing board (not the screen).

Public and private sector, low and flat, tall and skinny: DCM projects shape Melbourne, Sydney and Canberra. Their formal investigations range across important building types and urban spaces of the late 20th century—tall building, embassy, museum, civic square and some inventive hybrids. Natural divisions in architectural practice fall between these types—the firm that does office buildings doesn’t do public buildings. DCM successfuly bridges these gulfs because the work, although tangentially informed by a body of theory, arises organically from a deep consideration of program, site and client. Denton and Corker are able to shape and clarify their clients’ dimly perceived vision for a project and Marshall crystallizes it though his virtuoso draftsmanship.

Architectural success usually follows a conventional course, beginning with a house for parents, through successively (allegedly) more complex buildings, groups of buildings and finally to urban design. Object fixation begins early. DCM inverted that succession. Les Perrott advised a young Denton that success lay in the combination of architecture and urban planning. For that prescience, DCM should be eternally grateful. Both Denton and Corker took second degrees in planning. Both began work in the multi-disciplinary practice of Earle Shaw & Partners. The early work of the partnership was not architecture but planning—planning and designing the brave new (short-lived) world of Whitlam’s Australia. Buildings and space became part of an urban continuum. The relationships between them were studied. Individual buildings were seen as fragments of a larger whole and (in Marshall’s words) “not so precious”.

No work at this level exists in a vacuum. The tides of architectural fashion are present in DCM’s work—neo-rationalism in Parc de La Villette, OMA in some recent projects. But the work has an underlying formal rigour and strength unusual in practices of this size, which can be traced back to Hugh O’Neill’s excellent basic design course in the first year at the University of Melbourne. For the receptive student, here was a superb introduction into the structure of space and light, plan and section; the expressive potential of colour, texture, materiality. DCM all took that course in 1963 and all did well. Aside from the stylistic influences, a strong formal core runs through the work. Much of it can be described as an ordered field within which there are discontinuities, often signifying important programmatic elements or making urban gestures. A coolly rational extrusion, the Melbourne Exhibition Centre’s inclined blade marks the entrance and counterpoints the relentless rectilinearity of the city skyline.

The Beatles’ first appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show had all the marks of a Berger vertical invasion. Sullivan appeared somewhat uncomfortable and the Fab Four couldn’t quite believe their success. DCM have that air. Although they’re 50 and have been in practice 25 years, there is still the sense about them that they don’t quite belong, that their position is tenuous. It explains their popularity among peers in a field and a nation usually merciless to the successful. The maintenance of it will be the key to a continuing creative evolution of the collaboration.

|