The “raw and uncompromising” facade of the Grey Gums Apartments. The affordable housing project is sited at the Kelvin Grove Urban Village, two kilometres from Brisbane’s CBD. Image: Jason Haigh.

The articulated street frontage shows the palette of materials used at Grey Gums. Image: Graham Philip

Materials are chosen for their inherent qualities. The breezeblocks of the private balcony provide adornment to the building facades. Image: Graham Philip

The apartment blocks as seen from the public driveway. Image: Graham Philip

Detail of the communal area at the entry to the “pedestrian spine”, the main strategy for promoting sociability. This links to stairways accessing the upper-level units, and allows a through-site link from the street front to the park beyond. Image: Graham Philip

Looking along the pedestrian spine to the entry. The rainwater tanks, which service water-efficient toilets for each unit, also clearly express the project’s commitment to biophysical sustainability as well as social sustainability. Image: Graham Philip

An upper-level circulation space. The detailing of the stairwell wall allows for small recesses at the entry point of each of the apartments. Image: Graham Philip

Interior views of an apartment. Images: Graham Philip

A private, semi-enclosed balcony space showing the framed view to Grey Gums Park beyond. Image: Graham Philip

Everything is tight when it comes to designing affordable housing projects in the inner city – limited budgets, strictly controlled time frames and tricky sites disregarded by others are all commonplace to this challenging architectural problem. Gall and Medek faced these restrictions and more when designing Grey Gums Apartments in Kelvin Grove for Brisbane Housing Company, yet they have seized the opportunity for a thoughtful architectural response. Their bold move to give priority to the social realm is laudable and regrettably uncommon. In most housing projects, affordable or otherwise, any “extra” space is carved up into privatized elements – a tiny courtyard here or an extra few centimetres on a balcony there. Rarely are shared spaces provided. Communality is the baby that has been thrown out with bathwater tainted by antisocial behaviour in mass housing projects, but hardly relevant to most Australian contexts. In this complex of 27 units, however, anything spare is given over to creating social possibilities. By carefully considering such issues as pedestrian routes through the complex and views between and beyond the units, and by exploiting the social potential of small spaces around doors and landings, the architects have created a place that encourages social life to evolve. Rather than cars or rubbish bins, there is a real sense here that people are the primary concern. A prominent communal water tank signals that environmental sustainability comes a close second.

The main strategy for promoting sociability is a carefully designed pedestrian spine through the site on ground level, which links to stairways and landings that provide access to upper-level units. It begins at a communal area with seating, letterboxes and a brightly coloured, tiled feature wall at the street frontage and leads to the large, five-storey massing of units at the rear of the site. While I was visiting, I saw people using the space for more than just reaching their units. School-aged children played handball, the designated bicycle parking area at the rear of the site was accessed with ease, shopping was carried in, rubbish out, and a young man sat in the space at the street waiting for a friend to come over. On upper levels, tenants have placed doormats and potted plants in the small recesses created at their front doors by the subtle extension of stairwell walls. The broad, blockwork ledges of private balconies were brimming with plants and decorative garden features. There are strong echoes of Herman Hertzberger here, where every building element is considered for its social potential. This does not mean, however, that privacy and safety are disregarded. On the top floor, a woman came to her front door when our unfamiliar voices floated through the louvred fanlight. Breezeblocks provide both visibility and privacy to balconies located adjacent to landings.

Bold moves have a cost, and in this case it is probably the finish of the building. Raw and uncompromising, Grey Gums Apartments spurns the use of render or applied finishes, even paint – materials are chosen for their inherent qualities. Concrete blocks, columns and breezeblocks are combined with steel balustrades, rafters and wide-pan sheeting. Detailing is simple, even forthright. Adornment is not avoided but is achieved through colour and patterning of structural elements. This is all completely conscious; the architects declare that they are “happy for the building to wear its heart on its sleeve”. Architectural honesty, however, is not always so well received by affordable housing tenants. Most are in positions where their housing choices are severely restricted and they generally express preferences for discreet buildings, whose most distinguishing feature is that they are indistinguishable from the mainstream of private housing.

Only time and habitation will reveal whether the architectural boldness of the scheme marries with tenants’ needs and aspirations. I visited the building recently with the project architect and tenancy manager. While we were chatting, several people wandered through the site, making use of the pedestrian connection from the public park at the rear to the street at the front. The architect was delighted, the manager dismayed. This conundrum is what makes good design so fundamental to successful social housing.

Gall and Medek are known for their commitment to sustainability. Project architect Jason Haigh explains that this is as much an interest in “not sustaining the unsustainable”. A modest claim, yet Grey Gums Apartments boasts some significant environmental achievements. Energy consumption is minimized through attention to the building’s passive thermal performance and the interplay of heavily insulated lightweight construction and thermal mass, as well as the use of a recirculating, instantaneous gas hot water system and fluorescent light fittings. There is no airconditioning and bathrooms are naturally ventilated. Roof water is collected in a series of elevated tanks, then channelled to a large central tank that services water-efficient toilets for all 27 units. Rainwater is also used in an irrigation system for gardens and for various outdoor purposes, such as cleaning cars.

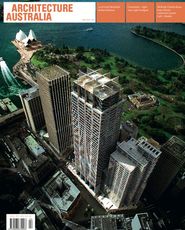

The design of Grey Gums was subjected to greater regulation and scrutiny than most housing projects, affordable or otherwise. Grey Gums Apartments are located in the Kelvin Grove Urban Village, an ambitious partnership project between the Queensland Government (through the Department of Housing) and Queensland University of Technology. The 16.57-hectare site of the village was formerly the Australian Army’s Gona Barracks and is located just two kilometres from Brisbane’s CBD. In terms of design, the Department of Housing keeps its hand firmly on the rudder. Developments in the urban village are controlled by a masterplan and then subject to the Kelvin Grove Urban Village Local Plan and Design Guidelines, as well as Brisbane City Council’s City Plan. The designs of all buildings in the village have to be approved by a Project Control Group at both concept and design development stages. In addition, the client, Brisbane Housing Company, has its own design guidelines. It is interesting to contemplate just what difference this level of regulation achieves. I suspect that the strength of the architecture of Grey Gums Apartments is partly the result of a robust process of negotiation where the architects had to be very clear about their intentions – and fight for them!

In valuing the social and environmental sustainability of the building, the architects were strongly in sympathy with their client. Brisbane Housing Company not only develops affordable housing but also manages it, making the consequences of design decisions extremely important. Every decision matters – the company itself has to deal with disputes between tenants, which may be due to noise transfer or the use of communal spaces; every exterior surface that doesn’t require ongoing maintenance has a direct impact on the rent they ultimately charge their tenants. Since its establishment in 2002, BHC has recognized the importance of design by the constant presence of an architect on their board. This is currently Eloise Atkinson, who has recently completed a Churchill Fellowship studying the design of affordable housing in North America and the UK. In teaming up with architects such as Gall and Medek who believe that affordable housing is about “making more housing with less”, BHC is leading the field in building affordable housing that is also meaningful architecture.

Credits

- Project

- Grey Gums apartments, Kelvin Grove Urban Village, Qld

- Architect

-

Gall and Medek Architects

- Project Team

- Jason Haigh, Bruce Medek, Jim Gail, Amy Hennessey, Teresa Wuersching

- Consultants

-

Builder

DTBS

Civil engineer Lambert and Rehbein Brisbane

Electrical engineer Ashburner Francis

Hydraulic consultant H Design

Passive thermal design consultant Energy Rating Consulting

Quantity surveyor Flavio Costanzo

Structural engineer Bligh Tanner

- Site Details

-

Location

Kelvin Grove,

Brisbane,

NSW,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

- Client

-

Client name

Brisbane Housing Company