Communities and cultures “grow” from places and in places. Improving the environment in which we live requires an earnest dialogue with both people and their landscape, and an acknowledgement of the relationship between the health of a community and the quality of its context. Community wellbeing or social capital distils down to how members of a community engage with each other and their environment, and whether they have a say in changing their existing condition into a preferred one.

The question is, who then is taking responsibility for “growing” society? We deploy the term “grow” in the qualitative sense (such as “personal growth”), building “social capacity,” implying improvement, nurturing, coordinating community efforts and connecting the threads that develop a holistic society. To make the place we live in into a better place requires mutual responsibility and shared effort between communities with a common interest, rather than reliance on “someone else” to do the heavy lifting.

The “growing society” responsibility also requires good governance and for Australia, the rubber hits the road through a democratically elected municipality. Working between the gaps are myriad state and federal government entities, including non-government organizations and not-for-profit community groups, which from experience seem to suffer from poor funding, connectivity and bigger- picture coordination.

To add to the complexity, Australia’s governance culture is biased, favouring economically driven politics over balancing the social and landscape (environmental) values. The result is that decisions on public works are often aligned with short-term economic and political timelines and agendas. This is now at a point where public capacity building projects may be influenced more by the global marketplace than by a local need, resulting in poorly targeted and often unnecessary interventions.

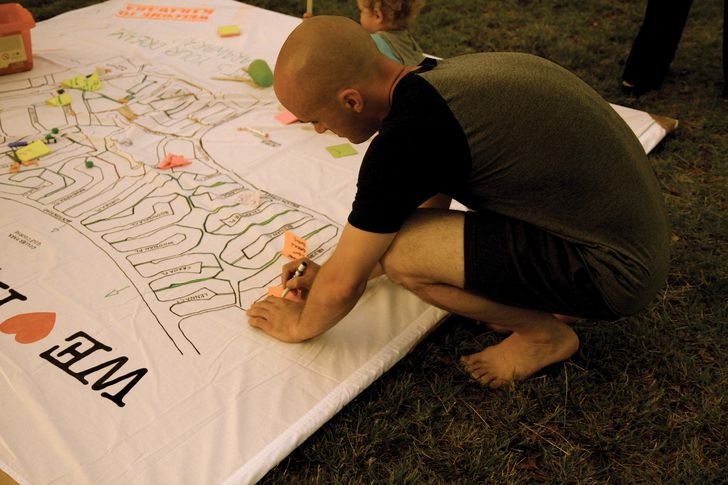

An example of participatory design grounded in the site and the community rather than confined purely to the studio.

Image: UDLA

To add further to this unbalanced dilemma, we are now recognized to be in the “age of disruption” due to unprecedented population, social and technological change. It is a world that is hyper-connected, influencing technological innovation on a level that is leaving the populace disconcerted and unable to keep abreast of change. Governing bodies have not yet introduced suitable policy that responds to these changes in society, instead providing non-effective leadership in navigating the new way society is connecting and interacting. For example, in the United States the Intuit 2020 Report Twenty Trends that will Shape the Next Decade predicts that by 2020, 40 percent of the workforce will be freelancing through online businesses such as Uber, Airbnb and Airtasker. The taxi industry and Australian tax laws still do not have policies that deal with these online global businesses (the “Google tax” issue). It is a time when professions need to be light on their feet, adapt to change or risk becoming invalid as the skills and the employment environment constantly evolves, where new job positions previously undreamt of are literally created overnight.

Within this complex context our practice, UDLA, is discovering new frontiers on old ground, in the section of urban fabric that is known as greyfields or brownfields – suburban areas that suffer from a lack of focused governance and reinvestment. These areas are often “outclassed” by the city centre or new and shiny greenfield development, pushing the urban fringes that spruik better housing and “greener, more sustainable” open-space amenity. Brownfield infill community development projects could be said to be our new frontier or mission.

“Walking the cracks” – the space between the outer urban development front and the more amenity-rich inner city area is where landscape architects can now flourish.

Image: UDLA

Putting the appeal back into the established twenty- to fifty-year-old ’ burbs that fill the space between the outer urban development front and the more amenity-rich inner city area is where landscape architects can now flourish. However, this requires our profession to deal with communities and areas that suffer the gap of poor governance, to be facilitators or coordinators of design and to be prepared to engage with local politics and “struggle street” conditions. Many of these communities do not feel empowered, due to not being able to have a say in changing their current condition into a preferred one, and many do not trust a municipality that they believe has turned their backs on an area, in some cases for three generations.

Professional experience has shown us that public, including culturally sensitive, design requires an integrated approach. Designers should incorporate an understanding of the broader context while acknowledging that robust solutions are often found in the “cracks” between disciplines – between the traditional responsibilities of town planners, technicians, geographers, anthropologists and other such professions. Design should not occur solely in the vacuum of the studio; we should not assume that it deals with a static condition. Design should be understood as a fluid, open and engaged process unafraid to get its hands dirty as it negotiates political, social and natural systems. In this way the discipline of landscape architecture can become the glue that fills the space between the uncertain interdisciplinary edges, providing coherence and certainty in the process of public realm design.

Our team has been encouraging a participatory design approach that aims to nurture and “grow” citizens’ capacity through design education. This motivates people to improve the capacity of communities, including positively affecting social, cultural, ecological, economic and political agendas. But where a participatory approach is not taken, the end user can be left feeling powerless. Public engagement expert Dr Don Lenihan explains that “traditionally, policy (planning) in the public realm can be said to be a competitive process where within the power stakes there are winners and losers. The winners tend to be the policy makers (designers) who hold the power of decision whereas the loser tends to be the end user who is required to accept the outcomes without the possibility of participating within the decision- making process.” 1

With careful design guidance from the facilitator, the participatory approach includes sharing educational tools such as design analysis, evaluation, use of similar project precedents and exploring development scenarios. This directly places the public within their design process. When performed correctly a participatory design approach increases the capacity of the community, including providing substantial benefits to the design outcome. Facilitation and coordination practices should continue beyond the design itself in order to assist the community in finalizing their community development project, leading to a sustainable result that produces a strong sense of ownership for the community, no longer the “designer’s project,” but rather “the people’s.”

Techniques for optimal participation also involve working with established community and stakeholder groups, rather than imposing purpose-built committees. It does quickly become evident that active people within smaller communities are already stretched, often over-worked and involved in the delivery of many menial community tasks. Finding a way to support these local champions can often be the beginnings of allowing space for brownfield communities to develop or grow in new directions.

As communities within the brownfields of our urban fabric move into obscurity, a new frontier enabled by the ability to adapt and relate can be realized for landscape architects. The “great generalists” who are able to draw from a wide artistic, social and scientific palette can then positively influence those spaces between people, their built environment and landscape ecology. The profession can realize this shared responsibility to fill the cracks between disciplines and promote governance that has a genuinely balanced approach to growing society.

1. Don Lenihan, Public Engagement and Co-design for Wicked Problems , Gov 2.0 Radio, 11 May 2012, gov20radio.com/2012/05/public-engagement/ (accessed 21 May 2015).

Source

Discussion

Published online: 8 Oct 2015

Words:

Daniel Firns,

Greg Grabasch

Images:

UDLA

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2015