The architect Roy Grounds (1905–1981) developed the original Hamer Hall design in the 1970s, but died before its completion. The Arts Centre brought in John Truscott (1936–1993), a noted actor, art director and costume designer, to rework the interiors. In this current refurbishment the largest external change is on the north side of the hall’s podium, facing the Yarra River and next to the Southgate shopping precinct.

Previously, Grounds had given it a rare and inventive treatment, casting its podium as a mirror image of Princes Bridge to its immediate east and in doing so making the bridge a historical tissue stretched at right angles across the base of the hall. This treatment also cast Hamer Hall as a renewed Castel Sant’Angelo juxtaposed with its Tiber Bridge. This is an immediate and appropriately evocative picture-postcard image (and the setting for Puccini’s Tosca) as encouraged by Charles Moore and arguably subscribed to by Grounds. 1 It complements the Renaissance palazzo imagery of his National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) found further along St Kilda Road.

Grounds is often seen as a major modernist figure in Australia (as in purism or functionalism), but there was plenty in his later design that engaged the plural and inclusive, that phase of architecture embodying postmodernism at its outset, before Charles Jencks’s urgings and the routine of practice made it universal, binary, classicized, teachable and diagrammatic. 2

The major problem was that in Grounds’s design the lower floors had no visual access either to the river or to Southbank, so the complex remained largely opaque when seen from the central city. ARM Architecture has opened up the podium, flooding it with internal light and making it an animated forum of people after dark, so that the concert hall’s festive role – the evening dress of finery and glow that Charles Garnier expected of his Paris Opera (1861–72) – would literally radiate across the water. Festive activity is now channelled through the river’s light reflection. The Hall’s riverside levels are cast as a virtual proscenium, with a casual pattern of drapery in its window shaping that seems pulled aside to reveal the life in the foyers and bars.

Hamer Hall’s riverside levels are cast as a virtual proscenium, with a casual pattern of drapery in its window shaping that seems pulled aside to reveal the life in the foyers and bars.

Image: John Gollings

This part of the hall relates to ARM’s “lantern” buildings – the Albury Library (2007) and the Marion Cultural Centre (2001). But the scale of this new drapery, or more correctly the plasticized concrete abutments around its window cut-outs, is perhaps the most surprising aspect in the new external grain. We have seen such scale before, in ARM’s Brunswick Community Health Centre (1990), parts of its National Museum of Australia (2001), or even in the squeezed and bubbling condom of Melbourne Central’s mall bridge across Little Lonsdale Street (2005). Hamer Hall’s new external massing sets up tracts of deep solidity that is in turn challenged by the spaces below, where a spiral pattern twists its way through a glass-walled performance space, through the riverside restaurants, and on to the matching twist and gauge of Clement Meadmore’s sculpture at the west end. ARM’s twisting line is both signature and expansion, recalling the aerial, faceted and planar cords of the National Museum of Australia and its Federation Square design.

The new riverside foyer provides access directly from the riverbank promenade to the dress circle.

Image: John Gollings

At Hamer Hall the winding cord is subterranean, presaging the cave-like and cyclopean character of the auditorium inside. It resurrects the Dreamtime imagery of the Rainbow Serpent, intended by Grounds as a central, germinal image for the Hall but discarded by the Arts Centre while the building’s design was developed. ARM repeats the serpent pattern higher up as well, setting it into the upper foyer carpet so that it trails through each gathering throng on St Kilda Road nights.

Grounds and Truscott had a debate here in concrete and acoustic materials. 3 The proposition was Grounds’s brutalist, almost primeval vision of a concert hall in brooding masses of bush-hammered concrete and jarrah surfacing, recalling the mood of Salzburg’s open-air Festival Theatre, 4 the film sets of Ingmar Bergman’s medieval dramas 5 or the hazy castles and crags once surrounding Laurence Olivier and Orson Welles. 6 In turn, Truscott shaped a cave-image much closer to Piranesi’s The Prisons, 7 with faceted boulders on the interior, sprayed rock layers on the concrete and cables, rings hanging from the ceilings and unseen heights behind the proscenium. These images were all heightened and made sprawling by the sheer size and T shape of the hall, making it the ideal setting for titanic music.

A general, if unspoken, expectation of the architectural community was that ARM would reassert the hero Grounds and expunge the interloper Truscott. But ARM’s intervention reaffirms both. Ian McDougall senses that Grounds conceived the hall in some way as a primeval ruin and that Truscott amplified this idea in his scenographic geology of the auditorium’s painted-stone layers. This balance is retained, and the original spray painter was recalled to refresh sections of his earlier work. Truscott’s auditorium carpeting, in its different batches, was painstakingly rematched. Where possible ARM has kept the diamond-point rustication of the auditorium’s wall panels (some produced major acoustic interference around their recessed “channel joints”). It has also kept one of the auditorium’s most imposing aspects: the grand and powerful blind panel, the inverse proscenium that frames the auditorium’s upper circle.

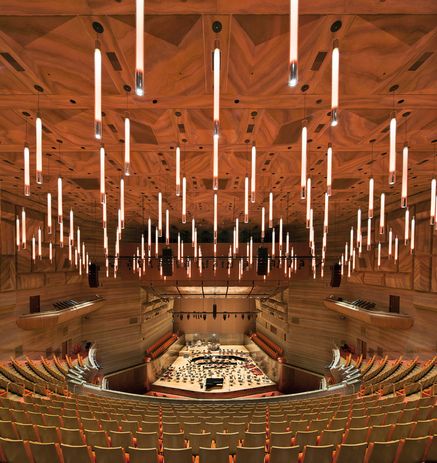

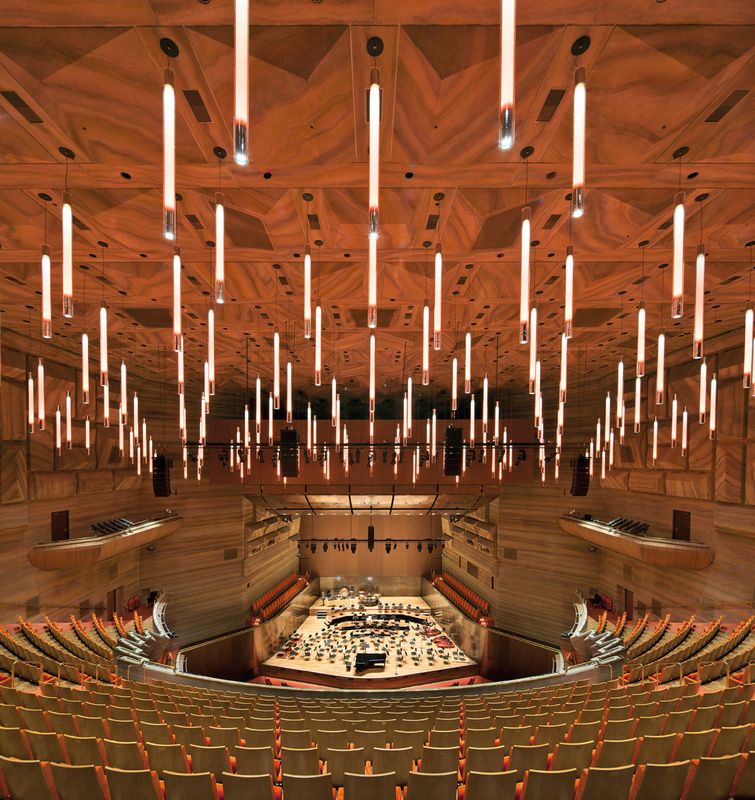

The other alterations to the auditorium are largely acoustic, though with significant visual results. ARM has flattened out and reduced the stepped balcony, a spectacular dead spot in the original acoustics and a source of similar difficulties in the stalls. In the process it has reduced the auditorium’s sense of a T shape. This comes through in the stage ceiling, where the copper walls and ceiling of a reflective “room” supplant the former array of dangling tubes and plastic doughnuts, and where a wraparound sedilia wall of black bronze and sandwiched timber reworks the thick, layered side and rear walling that ARM had used earlier in its Melbourne Recital Centre (2008).

The auditorium’s suspended tube lighting, like a sea of glowing batons, sustains the shining lights and embodied movement of the Hall’s annular foyers.

Image: John Gollings

The stage’s backing space is screened and otherwise vacant, pending the organ’s projected ten-million-dollar overhaul, and a massive fly-tower array with electronic stage machinery has been added, reflecting the range of popular music formats increasingly sought by hall renters. The stage-side control booths, a conspicuous Grounds signature initiated in his earlier Robert Blackwood Hall at Monash University (1965–71), have been subdued and in part re-sited. The original sound-deadening auditorium seats have been completely replaced, each now coming with a high timber back and reflective upholstery.

The result, in general, is a restrained but firm restatement of the original hall’s presentation as a contained, imposing, richly dark space, and distinctive in those qualities. In its more contained appearance it now looks closer to the rectangular shaping of the best auditoria: the two earlier Leipzig Gewandhaus auditoria (1781, 1884), the Vienna Musikverein of Theophil Hansen (1870), the Amsterdam Concertgebouw (1888) or that talisman of Melbourne’s sister city, Boston Symphony Hall by McKim, Mead and White (1900). Of these, only Boston’s hall has a similar number of seats. The Hamer Hall auditorium, though still massive, is now distinctly more intimate than its previous incarnation: the view from the rear circle, which resembled a gaze into some volcanic crater, is now more visually connected with its boundaries and with side and stalls spaces. There is more visual sense of the audience sharing the music in a newly compressed, cuboid space, rather than being cast as clusters of people, occupying different crags and escarpments in a landscape.

Bold bar lighting is a nod to the influence of John Truscott on the design of Hamer Hall.

Image: John Gollings

This new sense of spatial linkage, from one part or layer of the auditorium to another, carries through in links between the foyers and their welcoming festivity and the auditorium itself. The auditorium’s suspended tube lighting, like a sea of glowing sticks or batons, sustains the shining lights and embodied movement of the Hall’s annular foyers, at least till the performances start and the lights go down. This is carried through formally in several ways: the upper circle’s reverse proscenium is now given a grand imprint image behind the second-level bar, rather as J. J. Clark’s imprinted arcade is reflected in a breakfront at the rear of his Old Treasury round in Spring Street (1858–62).

Piranesian vistas from the stalls through to the St Kilda Road foyer.

Image: John Gollings

The angled foyer escalators, responding to the vortex embodied in the auditorium, recall the turbulent order of stairs and escalators in the foyers of Hans Scharoun’s Berlin Philharmonie (1963), but they have also been doubled in width and now run in direct sequence, distinct from the famously inadequate vertical transport of larger Grounds buildings (think of his original NGV and Robert Blackwood Hall). The entry areas have been darkened and are closer to the auditorium interior – compare with the blazing glow of the original promenade-hall entries and their silica-crystal glow. A crucial component here has been the removal of Michel Santry’s Arcturus sculpture. Arcturus’s other prime function was in linking the foyer floors through a common vertical space, but ARM believed the upper foyer needed flooring over to create a more coherent space. This has meant that the sculpture’s spatial rationale has gone and with it, the sculpture.

The view across the refurbished dress circle foyer to one of the many new bars. A newly commissioned artwork by Robert Owen, Falling Light, can be seen on the ceiling.

Image: John Gollings

Originally the major visual contrast inside Hamer Hall was between the brooding, cyclopean auditorium and the white light, gilded ceilings and teeming movement of the foyers. The main linking motif was in the foyer walls, which resembled the rusticated stone imagery of the auditorium but which were actually of cushioned leather. This polarity has been levelled out, and the demeanour of each realm recast. Both auditorium and foyers are more formal in tone. The light levels are closer. And audience movement along with its expression is carried more evenly through both areas. Hamer Hall’s main internal contrast now comes mostly from casual spacing and the shapes of the riverside foyer and the bars and restaurants below, where the river is linked to the hall through a new wall of basement glass.

In the new Hamer Hall podium ARM’s zigzagging glass wall runs throughout like a whispered chorus from that other concentric plan in Grounds’s career: the Shine Dome at the Australian Academy of Science in Canberra (1956–59). The Academy’s sense of shading, the encircling glass against the water and the arcaded solid layer around it are all restated and reworked in Hamer Hall. Of course, a zigzagging wall of glass was seen first in the NGV clerestory nearby.

Another Grounds motif in the ARM auditorium is the copper – rubbed, burnished, and beaten into soffits and towering panels – as first seen in Grounds’s houses of the 1950s and at Ormond College (1957–59). This is picked up again in the orchestra’s loft area.

Context is, as always with ARM, not only about immediate surroundings, but about what may be lost, imperilled or geographically distant but at the same time vital to the meaning. The first can be seen in the zigzagging trenches in ARM’s Shrine of Remembrance extension (2003), or in its city shop arcades and laneways of the 1930s to 1950s embedded in the National Museum. In Hamer Hall it is geographical distance that is alluded to, in the imaging of Grounds’s mostly discarded plywood baffles from the 1960 gallery two doors away. After all, in 1962 Grounds had proposed that his Victorian Arts Centre entertain a pre-eminently Victorian industrial image from the hub of Queen Victoria’s empire: a transported and rebuilt London Coal Exchange (1847–49), a crucial signature of nineteenth-century industry and commerce that was about to be demolished. 8 As with Grounds’s Rainbow Serpent idea, this proposal astounded contemporaries and was quashed in great haste. ARM has made all manner of functional improvements, but what marks out this refurbishment is the way it has been able to get inside the design’s original thought texture.

This project was also reviewed in Artichoke by Paul Walker.

1. Charles Moore, “You Have to Pay for the Public Life,” lecture, Columbia University, September 1978. Perspecta, 9–10, 1965, 57–63. Published in Perspecta, 9–10, 1965, 57–63. The Renaissance, scenographic and plural referencing in the National Gallery of Victoria building are discussed in Dean Boothroyd and Gina Levenspiel (eds), Backlogue 3, (Melbourne: Halftime, 1999) in essays by Philip Goad (72–105) and Conrad Hamann, (118–137). Grounds talked about the significance of remembered tourist scenes in a 1978 interview with the author. Both Philip Goad and the author have talked about the Castel Sant’Angelo in various settings for some years.

2. Conrad Hamann, “Off the Straight and Narrow,” Architecture Australia, June 1984; and Post-Modernism, in Philip Goad and Julie Willis (eds), The Encyclopedia of Australian Architecture, (Melbourne: Cambridge, 2011), 554–556.

3. Both Grounds and Truscott had previous careers in set and art direction in Hollywood. In the early 1930s Grounds worked for Sam Wood and other directors at MGM and RKO, and on films starring Wallace Beery and John Gilbert among other notables. Truscott gained fame with Warner’s 1967 film of the musical Camelot, where his art direction and costume design won two of the film’s three Oscars.

4. Or Kleines Festspielhaus by Eduard Huetter (1925–26), extended by Clemens Holzmeister (1937–38). See visit-salzburg.net (accessed 15 October 2012). Two million people saw its interior up close when The Sound of Music (1965) screened in Melbourne, making it effectively a postcard image.

5. The Seventh Seal (1957), The Virgin Spring (1960) or something akin to Hans Poelzig’s Der Golem imagery (1920), briefly pervaded photographic readings of the Sydney Opera House as a kind of Gothic city, giving commentaries on that building as an urban moment. See the images in Lucy Ellem’s chapter of Anthony Bradley and Terry Smith (eds), Australian Art and Architecture: Essays Presented to Bernard Smith, (Melbourne: Oxford, 1981).

6. As seen in Olivier’s Hamlet (1948) and Welles’s Macbeth (1948). As an occasional art director for film, Grounds would have been alert to the King Lear realm espoused in these, and they certainly matched his sensibility. Grounds’s “ruin” idea recalled Hans Poelzig’s Great Theater for Max Reinhardt in Berlin (1918–19, demolished 1988), or Basil Spence’s accord with ruins in Coventry Cathedral’s rebuilding (1955–1962). Grounds had visited Coventry Cathedral on his 1961 study tour. See Goad and Willis, 81.

7. Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Carceri d’invenzione (1745–50).

8. By J. B. Bunning; its demolition followed Taylor Woodrow’s demolition of Euston Station a year before.

Products and materials

- Walls and ceilings

- Class 2 off-form concrete to external walls. Elmo Elmotreasure leather wall panels, Bronzeworks bronze-tinted metal panels, concrete render, tinted mirror, coloured stainless steel, gold leaf and factory-applied high-gloss polyurethane panels to internal walls.

- Windows

- Polished stainless steel, anodized aluminium and patterned interlayer.

- Flooring

- Ground-floor foyer uses RC∞D hand-tufted custom-designed rug insert and Spanish orange and silver grey loop pile insert, Brinton custom Wilton woven cut-pile carpet in Earthern Brown, antique brown granite. Riverside foyer uses honed bluestone, spotted gum timber and Trend Cristallino reconstituted stone. Other foyers use Brinton custom Wilton woven cut-pile carpet matched to original colourway and Persian red travertine to match existing. Auditorium uses brushbox parquetry to match existing, Brinton custom Wilton woven cut-pile carpet matched to original colourway, spotted gum narrow board to stage.

- Lighting

- Lighting supplied by LED Lighting, Endo Lighting Corp, Eagle Lighting, Acdc, Lighting Group, Zumtobel, Clearlight Shows, Erlo, Xenian, Planet Lighting, Klik Systems, Thorn and Bega.

- Furniture

- Kelly low-back chair and Ned large ottoman in Kvadrat Maharam Mohair Supreme Earthern Brown, Albert coffee table with gold mirror and brass-plated frame, Jarvis low-back chair in Kvadrat Maharam Divina Melange 2 orange and light grey, Jarvis low-back 2.0 seater in Kvadrat Maharam Divina Melange 2 dark grey, Bandy coffee table, Milo lounge and small and large Coast ottomans all by Nick Garnham and Rod Carlson for Jardan. Maxalto Elios oval side table by Antonio Citterio for B&B Italia, La Santas Teresa Table lamp by Jaime Hayon for Metalarte, Chantilly Ottoman by Inge Sempe for Edra, all from Space Furniture. Mummy chair by Peter Traag for Edra from Space Furniture. Custom Figueras theatre seats with oak frame and Warwick mystere velour fabric in Persimmon.

- Bar

- Trent custom-built refrigeration. Joinery fabricated by GOSA with high-polish brass fronts. Corian Glacier White worktops. Stone Italiana Super Black reconstituted stone rear counters and tinted mirror. Astra Walker Icon tapware. Zip chilled water fonts. Riverside counters include Baresque Illume in foil-backed orange and yellow.

- Bathroom

- Catalano wall-mounted basin and floor-mounted WC from Rogerseller. Astra Walker Icon tapware. Walter Knoll Vola soap dispenser from Dedece. Kyissa partitions. Cotto D’este Kerlite Black Absolute Style tiles on wall from Signorino tiles. Bisazza Opus Romano tiles on floor. Mirrors are custom designed by ARM and fabricated by GOSA.

- External

- Bluestone.

- Other

- Ground-level sculpture is Silence by Robert Owen (sculptor) and Rachel Burke of Electrolight. Velik foyer circle level sculpture is Falling Light by Robert Owen (sculptor) and Rachel Burke of Electrolight. Mobile merchandise stands custom designed by ARM and fabricated by Gamma Doura. Auditorium stalactite lighting custom designed by LDP Sydney.

Credits

- Project

- Hamer Hall

- Design practice

- ARM Architecture

Australia

- Project Team

- Ian McDougall, Howard Raggatt, Neil Masterton, Peter Bickle, Stephen Davies, Jonothan Cowle, Andrea Wilson, Rhonda Mitchell, Doug Dickson, William Pritchard, Justin Fagnani, Sarah Lake, Sarah Box, Timothy Brookes, Allira Davies, Paul Buckley, Thomas Denham, Matthew Ginnever, Asako Miura, Deborah Rowe, Simon Shiel, Monique Brady, Jason Lee, Ken Billan, Mordechai Toor, Martine de Flander, Mark Raggatt, Tom Marsh, Andrew Ta, Tobi Pederson, Natalie Lysenko, Lee Lambrou, Aaron Poupard, Andrew Lilleyman, Stephen Ashton

- Consultants

-

AV consultant

PLP Building Surveyors & Consultants, Hanson Associates

Acoustics Marshall Day Acoustics, Kirkegaard Associates

Building surveyor PLP Building Surveyors & Consultants

Contractor Baulderstone

Heritage consultant Bryce Raworth, Philip Goad, Bryce Raworth

Kitchen services consultant MTD Group

Landscaping Taylor Cullity Lethlean Melbourne

Pedestrian modelling Arup

Project alliance Southbank Cultural Precinct Redevelopment Project Alliance: Arts Victoria, Major Projects Victoria, Baulderstone, ARM Architecture

Quantity surveyor Rider Levett Bucknall – Melbourne

Specialist lighting Lighting Design Partnership

Structural & building services Aurecon

Theatre technical consultant Schuler Shook

Traffic consultant Cardno

Urban design Peter Elliott Architecture + Urban Design

Wayfinding ID/Lab

Wind consultant Vipac

- Site Details

-

Location

100 St Kilda Road,

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

Site type Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2012

Design, documentation 12 months

Construction 24 months

Category Interiors

Type Culture / arts, Public / civic

Source

Project

Published online: 21 Feb 2013

Words:

Conrad Hamann

Images:

John Gollings

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2013